Introduction

The Austrian Early Childhood Intervention Programme (Frühe Hilfen), includes regional Early Childhood Intervention Networks, that reach out to families in need and supports them in creating healthy environments for their children. With this objective in mind, mental, social and health resources, and the needs of all family members, are addressed by the outreach programme.

Peacock et al. (2013) stated that no single intervention is designed to meet the needs of every family. Therefore, Frühe Hilfen, with its home visits and referrals to other services, is just one part of a global support system and the very first element of prevention chains.

With its innovative approach to attending to specific needs of families and their children, Frühe Hilfen empowers and offers guidance to families who are most vulnerable due to short- or long-term strains and hence, hopefully, prevents toxic stress and adverse childhood experiences, for many children and their families.

The unique low-threshold approach of these networks succeeds to improve living situations and relational health and well-being. To summarize, early childhood is a vulnerable phase, but one with good chances to promote health equity.

Frühe Hilfen – Early Childhood Intervention Networks in Austria

Considering national characteristics and taking into account what has worked well for other countries, a standard model for Frühe Hilfen was developed for Austria in 2014 (figure 1). This model was developed upon:

- A literature review on conception of a universal basic offer in terms of time and content (Antony, Stürzlinger & Weigl, 2014) and

- A first needs assessment and experiences from the Austrian model region Vorarlberg and Germany (Haas et al., 2013).

As a result, the model combines universal and indicated prevention.

Figure 1. Indicated model for Frühe Hilfen. Source: National Centre for Early Childhood Interventions (NZFH.at).

The implementation of regional Early Childhood Intervention Networks is professionally supported and guided by the National Centre for Early Childhood Interventions (NZFH.at) (www.fruehehilfen.at). The national centre’s mission includes:

- coordination

- harmonisation and monitoring of the nationwide implementation

- quality assurance and improvement (ongoing training of family supporters)

- Further development of the scientific basis and quality standards

- evaluation measures, and

- knowledge transfer

Part of the monitoring is a nationwide data collection system (FRÜDOK) based on anonymized background information about supported families, documented by the family supporters. It is maintained and analysed by the Austrian National Centre for Early Childhood Interventions.

Background information includes:

- details about the referral and reason for support

- details on pregnancy or/and supported children

- data on the family situation

- information of referrals to other support services as well as

- data about the home visits and other contacts with the families or with professionals from support services.

Data is only collected if there is a written or oral consent of the family.

Up to this date, the indicated part of Frühe Hilfen – the so-called Early Childhood Intervention Networks – are established in all provinces of Austria. These are multi-professional support systems with centrally coordinated services for parents (to be), and children in early childhood that are provided in a low-threshold manner on a local and regional level.

Parents are not only defined as biological parents, but also as individuals acting as psychological parents fulfilling the social role of parents (e.g., patchwork parents, homosexual parents, foster parents, adoptive parents, or grandparents).

The Early Childhood Intervention Networks consist of:

- A multi-professional team for continuous and comprehensive family support.

- At least one person with the task of network-management

- A variety of regional and local service providers and professionals also function as gatekeepers for families.

Existing and available regional support services like pregnancy counselling, midwife services and broader health care are integrated with a multi-professional network that fosters interdisciplinary cooperation and development. Thus, individualised and need-oriented support can be offered to families.

Primary target groups are parents (to be)/families with multiple burdens such as poverty, job loss, illness etc. and a lack of resources. The focus is on the period from pregnancy up to a child’s third birthday.

Relevant burdens potentially initiating support by regional Early Childhood Intervention Networks are mainly social burdens (e.g., financial distress, social isolation, or unsecured/insufficient living space) or psychological strains (e.g., mental illness/addiction of the primary carer or partner, undesired pregnancy).

The Mental, social and health needs of the families are considered. Most of the families worry about their financial and social situation and are strained by the psychosocial health situation of at least one primary caregiver. Having an unplanned pregnancy, being very young when the child is born or having a disability is not that frequent amongst the families support but often seen as extreme burdens.

At least one-third of children from supported families show an increased demand for care, due to premature or multiple birth, congenital disease or disability, developmental delay or disorder or excessive crying, or feeding/ sleeping disorder (Marbler, Sagerschnig, & Winkler, 2020).

The core intervention of regional Early Childhood Intervention Networks directed to the primary target group is the so-called “family support”.

Family support is done by specially trained professionals like midwives, nurses, social workers, psychologists, or pedagogues. This intervention consists of regular contacts between the family supporter and the family, mostly conducted as home visits or other personal contacts within the families’ environments, supported by contacts via telephone and e-mail. The family supporter determines existing resources and burdens, identifies, and together with the parents, plans for the concrete need for support. They then organize and coordinate adequate support services.

For this kind of resource-oriented individual support, a trusting relationship, gained through empathetic conversations and small advice for everyday life during pregnancy or with a newborn/toddler, is a prerequisite. Quick help and the accompaniment to appointments and meetings is just as beneficial. It is based on voluntary participation and free of charge for families. Due to this low-threshold concept, vulnerable families are better reached increasing the potential of their uptake of services.

Theoretical background

The Austrian programme on Early Childhood Intervention Networks wants to support a healthy start in life for all babies, especially for those in burdened family situations. Therefore, the programme is evidence-based. For example, the programme is informed by World Health Organisation (WHO, 2020) and the evidence base from the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) (See Felitti et al, 1988; Gilbert et al., 2009; Kundakovic & Champagne, 2015; Shonkoff & Garner, 2011; Teicher & Samson, 2016).

Furthermore, “toxic stress” is a key concept regarding early childhood experiences and long-term consequences on health. While normal stress experiences are part of everyday life and cause only mild physical reactions, toxic stress leads to disorders of the brain and other organs and systems in the body (Danese et al., 2008; Gunnar, Morison, Chisholm, & Schuder, 2001; Massin, Withofs, Maeyns, & Ravet, 2001; McDade et al., 2005; Miller & Chen, 2007; Miller, Chen, & Cole, 2009; Overfeld, Buss, & Heim, 2016; Shirtcliff, Coe, & Pollak, 2009; Shonkoff & Garner, 2011; Stevens, Lauinger, & Neville, 2009; Tyborowska et al., 2018).

At best, the parent-child relationship with other protective social relationships are important resources for the child and protects them from the consequences of such hardship (Alio, 2017; Shonkoff & Garner, 2011). These protective factors also influence further life skills, including problem-solving (Grossmann & Grossmann, 2003).

So, it is of special importance to support parents and families with their children, in their communities, to reduce toxic stress and make way for them to be able to create environments that support healthy and safe child development.

Frühe Hilfen: Beginnings of family support

Early Childhood Intervention Networks come into place, aim to support families in burdened situations in a low-threshold manner to promote the healthy development of these children. In the long-term, this intervention aims to contribute to sustainable population health and especially to health equity.

To clarify the task and goal of the family support, an initial meeting is held with the family.

Thereby, a first assessment of the family situation and the support services already installed takes place. Attention is paid to the following aspects:

- the situation of the child (e.g., increased care requirements due to pregnancy or birth complications, congenital diseases)

- the situation of the parents (e.g., physical and mental health, education and employment situation, Single primary caregiver)

- the situation of other family members or relevant caregivers (e.g., siblings)

- parent-child relationship (e.g., parent-child interaction, attachment security, interactions between family members, a child with each other, custody situation of the child)

- partnership and family situation (e.g., family climate, family cohesion, disharmony, separation, early parenthood, unplanned pregnancy)

- living conditions (e.g., network, household financial situation, housing conditions)

- Specific resources (e.g., social and emotional support from the social environment, Confidence/optimism, religion/belief, personal coping skills or coping strategies)

- specific stresses (e.g., postpartum depression, overwhelm and fears about the future, poverty, homelessness, trauma, violence, neglect, stressful caregiving responsibilities such as many children, siblings with illnesses or disabilities, dependent adults, etc.)

Who are the families?

Nearly 6.000 families and more than 5.000 children under 3 years of age have been supported so far by the Austrian Early Childhood Intervention Programme. The families are often overwhelmed with the situation, have strong fears about the future and show a variety of burdens.

Differences in health outcomes and development of children are strongly linked to their social background. Children from families with a lower socioeconomic status experience poorer health and are more likely to be unsuccessful in school (Marmot, 2010; Melhuish, 2014).

The Early Childhood Intervention Networks succeed to reach (socially disadvantaged) families in needs, often during pregnancy or shortly after birth.

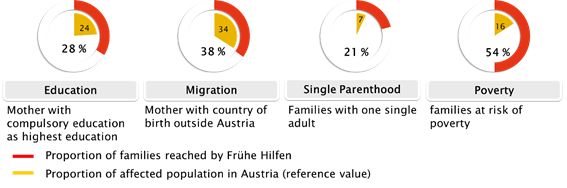

Data analysis of supported families showed that:

- More than 50 per cent of them can be characterised as poor or at risk of poverty (compared to 16 % of families with children under three years in the whole population)

- Almost a third of the primary caregivers have no higher education than compulsory school (compared to 24 % of women aged 15 to 44 in the whole population)

- More than a third are not born in Austria (compared to 34 % of all mothers who had a child in 2018)

- Nearly one quarter are single parents (compared to 7 % of families with children under three years in the whole population). (Kaindl & Schipfer, 2019; Marbler et al., 2020; Statistik Austria, 2019a, 2019b) (see also figure 2).

Figure 2. Characteristics of supported families. Source: National Centre for Early Childhood Interventions (NZFH.at).

Furthermore,

- 30 per cent of all mothers are, or have been in treatment because of a mental illness and about 10 per cent show signs of postpartum depression at the beginning of family support.

- At least 15 per cent of mothers have experienced violence once in their lives.

- Signs of acute violence within the family exist in about 7 per cent of all supported families (Marbler et al., 2020).

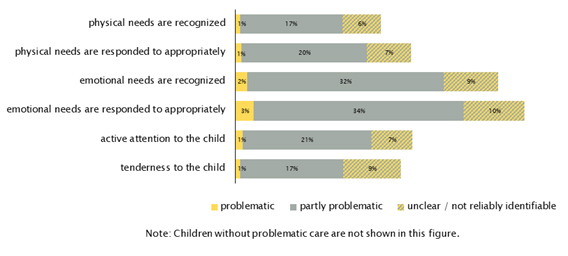

Difficulties regarding different dimensions of the parent-child interaction (recognition and/or acceptance of physical or emotional needs, active attention to the child or tenderness to the child) concern at least 43 per cent of all supported children (Marbler et al., 2020). (see also figure 3).

Figure 3. Problems with acceptance and care of the child, in the percentage of supported children. Source: National Centre for Early Childhood Interventions (NZFH.at).

Based on the individual family history and specific needs, the family supporter assists in finding appropriate support services.

- 1 in 5 supported families is referred to psychological services and/or to social activities like playgroups or mother/parent-child-meetings.

- Psychiatrists or psychosomatic treatments are referred to in 10 per cent of supported families.

- Further referrals are initiated to childcare, grants and subsidies, services for parental education, midwives, family and household assistance, pediatric practice or services that support bonding and so on (Marbler et al., 2020).

If several support services are installed in a family, there may also be family conferences with all the service providers involved to coordinate further action and not to overburden the family. In a recent study, families have highlighted that such an individual, comprehensive and fast support, really helped to better their situation (Weigl & Marbler, 2020).

Outcomes

Families are supported through empathetic and encouraging conversations with their family supporters, as well as through practical advice.

In a recent study, mothers told us, that these conversations were among the most important aspects of family support. They lead to a reduction of anxieties, improved their self-confidence and self-efficacy, and enabled the use of assistance and advice. They experienced being heard and learned that they are good parents (Weigl & Marbler, 2020).

Based on the feedback of the supported families, it is known that they are very satisfied with the support and experience an overall benefit of the intervention for all family members (Marbler et al., 2020).

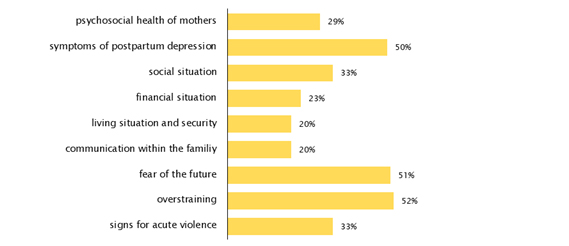

Data analysis showed that:

- The psychosocial health of mothers has improved in nearly 30 per cent of families and that 50 per cent of mothers with symptoms of postpartum depression have improved their mental health until the end of their family support.

- Further positive results can be seen for the social and financial situation of families, the living situation, the communication in families, the fear of the future, the overstraining and signs for acute violence.

- Also, the interaction with the child has improved in many families (Marbler et al., 2020) (see also figure 4).

Figure 4. Improved situations in families with burdens in specific areas at the beginning of family support. Source: National Centre for Early Childhood Interventions (NZFH.at).

Conclusion

The evidence-based Austrian Early Childhood Intervention Programme is effective as it supports parents in creating good conditions for the growth of their children.

Evaluation results from reports of supported families as well as the data collected within the programme) confirm that the short-term objectives of the Austrian Early Childhood Intervention Programme can be achieved.

Nevertheless, long-term effects on the development and health of children from supported families cannot be proven yet, as the programme is just implemented for five years and the methodology for such a study is also quite complex.

The programme is based on a key principle of voluntary participation. As the mandate for the support comes from the families themselves, they may also refuse further support from Early Childhood Intervention Networks, even if professionals see an on-going need for support. In some families, there are signs for endangerment of child welfare resulting in a respective report to child and youth welfare.

However, the evaluation reports on the Austrian Early Childhood Intervention Programme also show that the regional networks can only be successful if there are adequate resources allocated and necessary support services are sufficiently available in the region and are willing to cooperate with the network.

Peacock et al (2013), stated that no single intervention is designed to meet the needs of every family. The Frühe Hilfen, with its home visits and referrals to other services, is part of a global support system. It is the first element in prevention community chains. It is an innovative community based participatory approach, attending to specific needs of families and their children, Frühe Hilfen empowers and offer guidance to families who are most vulnerable due to short- or long-term strains.

Hopefully, this innovation prevents toxic stress and adverse childhood experiences for many children and their families. To summarize, early childhood is a vulnerable phase, but one with good chances to promote health equity.

References

Antony, K, Stürzlinger, H. & Weigl, M. (2014). Frühe Hilfen – Evidenz zur zeitlichen und inhaltlichen Konzeption eines universellen Basisangebots. Ergebnisbericht. Wien, Gesundheit Österreich GmbH im Auftrag des Bundesministeriums für Gesundheit: 48.

Alio, A. (2017). Toxic stress and maternal and infant health. New York: University of Rochester Medical Center, NYS Maternal & Infant Health Center of Excellence

Black, M. M., Walker, S., Fernald, L. C. H., Andersen, C. T., DiGirolamo, A. M., Chunling, L., & McCoy, D. C. (2017). Advancing Early Childhood Development: from Science to Scale The Lancet, 389(10064): 77–90.

Bos, K. J., Zeanah, C. H., Smyke, A. T., Fox, N. A., & Nelson, C. A. (2010). Stereotypies in Children With a History of Early Institutional Care. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 164(5), 411. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.47]

Danese, A., Moffitt, T. E., Pariante, C. M., Ambler, A., Poulton, R., & Caspi, A. (2008). Elevated Inflammation Levels in Depressed Adults With a History of Childhood Maltreatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 65(4), 416.

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14, 245–258.

Gilbert, R., Widom, C. S., Browne, K., Fergusson, D., Webb, E., & Janson, S. (2009). Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. Lancet, 373(9657), 68-81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61706-7

Grossmann, K., & Grossmann, K. (2003). Bindung und menschliche Entwicklung. John Bowlby, Mary Ainsworth und die Grundlagen der Bindungstheorie. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta.

Gunnar, M. R., Morison, S. J., Chisholm, K., & Schuder, M. (2001). Salivary cortisol levels in children adopted from Romanian orphanages. Development and Psychopathology, 13(3), 611-628.

Haas, S., Pammer, C., Weigl, M., Winkler, P., Brix, M. & Knaller, C. (2013). Ausgangslage für Frühe Hilfen in Österreich. Wien, Gesundheit Österreich GmbH im Auftrag der Bundesgesundheitsagentur: 123.

Kaindl, M., & Schipfer, R. K. (2019). Familien in Zahlen 2019. Statistische Informationen zu Familien in Österreich. Wien: Österreichisches Institut für Familienforschung

Koren, G., & Nulman, I. (2010). Drugs in Pregnancy. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 164(5), 495. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.64

Kundakovic, M., & Champagne, F. A. (2015). Early-Life Experience, Epigenetics, and the Developing Brain. Neuropsychopharmacology Reviews, 40, 141–153. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.140

Marbler, C., Sagerschnig, S., & Winkler, P. (2020). Frühe Hilfen. Zahlen, Daten und Fakten 2019. Wien: Gesundheit Österreich

Marmot, M. (2010). Fair society, healthy lives. The Marmot Review. Strategic review of health inequalities in England post-2010. London: Institute of Health Equity

Massin, M. M., Withofs, N., Maeyns, K., & Ravet, F. (2001). The Influence of Fetal and Postnatal Growth on Heart Rate Variability in Young Infants. Cardiology, 95(2):80-83.

McDade, T. W., Leonard, W. R., Burhop, J., Reyes-Garcia, V., Vadez, V., Huanca, T., & Godoy, R. A. (2005). Predictors of C-reactive protein in Tsimane’ 2 to 15 year-olds in lowland Bolivia. Am J Phys Anthropol, 128(4), 913. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20222

Melhuish, E. (2014). The impact of early childhood education and care on improved wellbeing. London: British Academy.

Metzler, M., Merrick, M. T., Klevens, J., Ports, K. A., & Ford, D. C. (2017). Adverse childhood experiences and life opportunities: Shifting the narrative. Children and Youth Services Review, 72, 141-149. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.10.021

Miller, G., & Chen, E. (2007). Unfavorable Socioeconomic Conditions in Early Life Presage Expression of Proinflammatory Phenotype in Adolescence. Psychosomatic Medicine, 69(5):402–409.

Miller, G., Chen, E., & Cole, S. W. (2009). Health psychology: developing biologically plausible models linking the social world and physical health. Annu Rev Psychol, 60:501-524. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163551

Overfeld, J., Buss, C., & Heim, C. (2016). Psychische und körperliche Krankheitsanfälligkeit. Die Bedeutung früher traumatischer Lebenserfahrungen. InFo Neurologie & Psychiatrie, 18(9), 30-40. doi: 10.1007/s15005-016-1782-9

Peacock, S., Konrad, S., Watson, E., Nickel, D., & Muhajarine, N. (2013). Effectiveness of home visiting programs on child outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Public Health, 2013(13), 17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-17

Shirtcliff, E. A., Coe, C. L., & Pollak, S. D. (2009). Early childhood stress is associated with elevated antibody levels to herpes simplex virus type 1. PNAS, 106(8), 2967.

Shonkoff, J. P., & Garner, A. S. (2011). The Lifelong Effects of Early Childhood Adversity and Toxic Stress. American Academy of Pediatrics, (30), e246.

Statistik Austria. (2019a). Bildungsstandregister: Bildungsstand der Bevölkerung ab 15 Jahren 2017 nach Altersgruppen und Geschlecht. Wien: Bundesanstalt Statistik.

Statistik Austria. (2019b). Mikrozensus-Arbeitskräfteerhebung 2018: Familien nach Familientyp und Zahl der Kinder ausgewählter Altersgruppen – Jahresdurchschnitt 2018. Wien: Bundesanstalt Statistik.

Stevens, C., Lauinger, B., & Neville, H. (2009). Differences in the neural mechanisms of selective attention in children from different socioeconomic backgrounds: an event-related brain potential study. Dev Sci, 12(4), 634-646. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00807.x

Stone, K. C., LaGasse, L. L., Lester, B. M., Shankaram, S., Bada, H. S., Bauer, C. R., & Hammond, J. A. (2010). Sleep Problems in Children With Prenatal Substance Exposure. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 164(5), 456. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.52.

Teicher, M. H., & Samson, J. A. (2016). Annual Research Review: Enduring neurobiological effects of childhood abuse and neglect. J Child Psychol Psychiatry, 57(3), 266. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12507

Tyborowska, A., Volman, I., Niermann, H., Pouwels, L., Smeekens, S., Cillessen, A., Toni, I., & Roelofs, K. (2018). Early-life and pubertal stress differentially modulate grey matter development in human adolescents. Scientific Reports, 8, 9201. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-27439-5

Weigl, M., & Marbler, C. (2020). Partizipative Erarbeitung eines Konzepts zur Begleitforschung im Bereich Frühe Hilfen. Gesundheit Österreich. Wien.

WHO. (2020). Framework on Early Childhood Development in the WHO European Region. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

Authors

Antony, Gabriele,

National Centre for Early Childhood Interventions (NZFH.at)

Austrian National Public Health Institute, Austria

Bengough, Theresa,

National Centre for Early Childhood Interventions (NZFH.at)

Austrian National Public Health Institute, Austria

Marbler, Carina,

National Centre for Early Childhood Interventions (NZFH.at)

Austrian National Public Health Institute, Austria

Sagerschnig, Sophie,

National Centre for Early Childhood Interventions (NZFH.at)

Austrian National Public Health Institute, Austria

Contact details: fruehehilfen(at)goeg.at