Abstract

This article explores the transformative potential of the JUSTICE framework in reflective supervision, particularly for supervisors and leaders working with diverse communities. Rooted in principles of social justice, equity, and inclusion, the JUSTICE framework offers a pathway for leaders to lean into discomfort, fostering growth and cultural humility (Rawls, 1971; Sen, 2009). By emphasizing bi-directional relationships and safe spaces, the framework equips leaders to address systemic barriers and engage in authentic, multicultural practice (Nussbaum, 2011). The article integrates global perspectives and a case study, illustrating the applicability of the framework across various cultural contexts. This article advocates for the JUSTICE framework as a necessary tool for advancing equitable reflective supervision, pushing infant mental health organizations to make a sustained commitment to social justice in leadership practices.

The Role of Reflective Supervision in a Changing World

Reflective supervision plays a critical role in navigating the complexities of cultural diversity and systemic inequities, particularly in today’s global landscape (Sen, 2009). Leaders who model vulnerability are key to this process, embracing discomfort and acknowledging their own limitations. This openness not only fosters spaces of trust where supervisees feel secure in their personal growth (Watson & Gatti, 2012), but also creates inclusive, equitable environments that value diverse perspectives and drive meaningful transformation (Sen, 2009). By addressing power dynamics and imbalances, leaders cultivate reflective spaces where both supervisors and supervisees can engage deeply in self-exploration, leading to profound personal and systemic change (Feniger-Schaal & Oppenheim, 2020).

When leaders invite discomfort into reflective supervision, they promote an atmosphere of emotional safety, encouraging supervisees to be honest and vulnerable. This approach bridges cultural differences and creates equitable practices that empower professionals to serve their communities more effectively. Reflective supervision, when rooted in vulnerability and trust, becomes not just a tool for personal development but a transformative force for systemic equity.

The JUSTICE Framework: A Global Tool for Inclusive Leadership

The JUSTICE framework (Hutchinson, 2023) is a powerful and holistic tool designed to guide supervisors and leaders in reflective supervision, helping them navigate complex and often uncomfortable conversations about diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). This framework empowers leaders to engage deeply, reflect on their own biases, and address systemic inequalities while fostering relational safety.

- J – Justice

- Justice within the framework refers to the equitable treatment of all individuals, ensuring decisions are free from bias and accounting for systemic inequities. Leaders using this pillar must reflect on the societal structures that disproportionately affect marginalized communities and make decisions rooted in fairness (Rawls, 1971). This involves a commitment to dismantling systemic barriers that perpetuate inequality.

- U – Understanding

- Understanding focuses on recognizing the long-lasting effects of historical trauma and ongoing discrimination. Leaders must actively work to understand how past injustices continue to shape present experiences. This deeper understanding allows leaders to create environments where individuals feel seen and valued, which is crucial for fostering psychological safety in reflective supervision (Nussbaum, 2011).

- S – Social Location

- Social location refers to one’s position within systems of power, privilege, and oppression. Leaders must reflect on their own social location and how it impacts their relationships with supervisees. Acknowledging social location enables leaders to address power imbalances in reflective supervision, creating more equitable and inclusive spaces (Sen, 2009).

- T – Transparency and Authenticity

- Transparency and authenticity are key to building trust in any leadership role. Leaders must be open about their vulnerabilities, biases, and intentions, modeling the behaviors they wish to cultivate in their teams. Authenticity allows for honest dialogue and helps create a culture of openness, which is essential for navigating difficult conversations about equity and inclusion.

- I – Inclusivity in Discomfort

- The framework emphasizes inclusivity in discomfort, recognizing that discomfort is a necessary part of growth. Leaders must create spaces where discomfort is embraced, ensuring that all voices, especially those from marginalized communities, are heard and valued. Inclusivity in discomfort encourages leaders to lean into challenging conversations, fostering deeper understanding and empathy (Nussbaum, 2011).

- C – Connecting with Emotions

- Connecting with emotions is central to the JUSTICE framework. Leaders must create opportunities for emotional expression, recognizing that emotions often stem from deep-seated experiences of trauma and resilience. By allowing space for emotional connection, leaders can build trust and foster genuine relationships with their teams, ultimately leading to more effective and compassionate leadership (Sen, 2009).

- E – Engagement in Safe and Brave Spaces

- Engagement in safe and brave spaces is the final pillar of the framework. Leaders must actively create environments where difficult conversations can take place without fear of judgment. These spaces should encourage vulnerability, allowing supervisees to express their thoughts and emotions openly. Safe and brave spaces are essential for fostering growth and transformation in reflective supervision (Rawls, 1971).

Application in Leadership

Leaders utilizing the JUSTICE framework can navigate difficult conversations about DEI (Diversity, Equity and Inclusion) with greater sensitivity and awareness. By focusing on justice, understanding, and social location, they ensure that their decisions are equitable and grounded in empathy. Moreover, fostering inclusivity in discomfort and connecting with emotions helps leaders build relational safety and trust, which are crucial for effective reflective supervision.

Through transparency and authenticity, leaders can model the vulnerability needed to create safe and brave spaces. This allows their teams to engage deeply in difficult conversations, ultimately promoting growth and fostering a more inclusive, equitable environment.

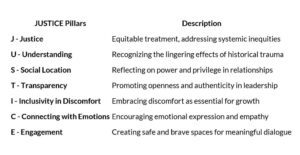

Table 1. The JUSTICE Framework.

The JUSTICE framework serves as a global tool for inclusive leadership, guiding supervisors and leaders in reflective supervision to engage deeply with the complexities of DEI. By leaning into discomfort, fostering transparency, and connecting emotionally, leaders can create environments where vulnerable, and transformative conversations can take place. The framework’s emphasis on justice, empathy, and engagement provides a solid foundation for leaders to navigate the challenges of equity and inclusion in a global context.

Leaning into discomfort is essential for growth in reflective supervision, as it creates space for leaders to confront their vulnerabilities and biases, ultimately leading to meaningful change. Discomfort often arises when leaders engage in discussions about power dynamics, cultural differences, or systemic inequities. By intentionally embracing this discomfort, leaders reflect deeply on their own positions and actions, fostering a learning environment where both supervisors and supervisees can grow together (Rawls, 1971). This reflective process cultivates emotional resilience, promoting authentic leadership in diverse and complex settings.

Practical strategies for fostering discomfort include encouraging open dialogue about challenging topics, creating safe spaces for vulnerability, and promoting transparency within the supervision process. When leaders model discomfort, they signal to their teams that growth often comes from leaning into difficult emotions rather than avoiding them. This approach not only strengthens the supervision relationship but also equips both leaders and supervisees to navigate the complexities of cultural and systemic challenges (Feniger-Schaal & Oppenheim, 2020). Embracing discomfort as a tool for growth ensures a deeper commitment to inclusive and transformative leadership.

Supporting Supervisors: Creating Brave and Safe Spaces

In climates where individuals or groups have historically faced marginalization, the idea of vulnerability can be daunting. For those who have been ostracized, opening up in reflective spaces may seem unsafe due to past experiences of exclusion and silencing. It is the responsibility of supervisors and leaders to provide the necessary scaffolding by creating brave and safe spaces, ensuring that vulnerability is met with understanding and support (Brown, 2018). Such spaces foster trust and inclusivity, allowing individuals to engage in honest dialogue without fear of judgment or retaliation.

By cultivating these environments, leaders enable growth through discomfort. Vulnerability becomes a tool for transformation, empowering supervisees to lean into difficult conversations and self-reflection. This scaffolding not only nurtures emotional safety but also strengthens relationships, ensuring that individuals from historically excluded communities feel genuinely supported and valued. The creation of brave spaces is essential for promoting authentic connections and encouraging risk-taking, which are key elements of personal and professional development (Bennett et al., 2020).

Empowering Leaders to Navigate Cultural Complexities

In an increasingly diverse world, leaders within infant mental health organizations are tasked with supporting a diverse group of multidisciplinary professionals, especially during multidisciplinary case staffing. These leaders must be equipped to navigate cultural complexities while addressing systemic inequities that impact both their teams and the families they serve. The JUSTICE framework offers a heartfelt and powerful approach to fostering multicultural relationships grounded in fairness, understanding, and inclusivity. By embracing this framework, leaders can create spaces where systemic inequities are confronted, and individuals from diverse backgrounds feel seen, valued, and empowered to contribute fully. This article delves into how the JUSTICE framework can be applied to leadership, focusing on addressing cultural differences, promoting equity, and building authentic, trusting relationships within an infant mental health setting

Understanding the JUSTICE Framework

The JUSTICE framework consists of six key pillars: Justice, Understanding, Social Location, Transparency, Inclusivity in Discomfort, Connecting with Emotions, and Engagement in Safe and Brave Spaces. Each of these pillars guides leaders in reflective practice and provides a roadmap for creating more inclusive and equitable environments (Hutchinson, 2023; Nussbaum, 2011). By focusing on both individual relationships and systemic structures, the framework empowers leaders to address power dynamics, foster trust, and build authentic connections across cultural lines.

Case Study: Applying the JUSTICE Framework in a Multicultural Organization

Background Context

A nonprofit infant mental health organization focused on supporting young children (birth to five) and their families employs a diverse multidisciplinary team (MDT) composed of professionals from various cultural backgrounds, including Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Cuba, Palestine, Israel, Nigeria, and individuals identifying as Black, African American, and Middle Eastern. These team members bring unique experiences shaped by trauma, systemic racism, and oppression. Recently, geopolitical tensions have intensified divisions within the organization, leading to a lack of understanding from leadership regarding the sociopolitical contexts affecting the families they serve.

The Challenge

The MDT encounters a particularly impactful case involving a two-year-old child exhibiting developmental delays linked to the family’s trauma and migration history. The child’s mother, a Palestinian refugee, is struggling with postpartum depression, exacerbated by feelings of isolation and the stress of her situation. The team feels increasingly stuck in their ability to provide effective support because leadership struggles with implicit biases, causing tension within the MDT. Leadership’s failure to grasp the sociopolitical context prevents effective collaboration and communication, resulting in feelings of frustration and disconnection among team members.

In a recent reflective supervision meeting, the MDT decides to implement the JUSTICE framework to address their challenges and enhance their support for the young mother and her child. They focus on the following components during their discussion:

- Justice:

The team prioritizes equitable support for the young child and her family. They advocate for tailored resources that specifically address the unique challenges stemming from the family’s sociopolitical context. By recognizing and addressing the systemic barriers faced by families in similar situations, they ensure that their practices prioritize fairness and accessibility. - Understanding:

To foster deeper understanding, the MDT organizes a reflective workshop where team members share personal experiences related to trauma and migration. They invite community leaders and mental health professionals to provide insights into the specific challenges faced by the families they serve. This shared understanding helps bridge the gap between leadership’s perspective and the realities experienced by families, fostering a culture of empathy. - Safety:

The MDT establishes ground rules to create a psychologically safe environment for open discussions. Team members are encouraged to voice their concerns regarding leadership’s implicit biases and the barriers these biases create in their work. This safety facilitates honest conversations about their experiences, allowing for vulnerability and healing within the team. - Trust:

Trust is cultivated through vulnerability and transparency. Team members share their challenges and successes in working with families, allowing for deeper connections and rapport. This trust extends to the families they serve, as the MDT learns to communicate more effectively and empathetically. - Inclusion:

The team actively works to ensure that the young mother’s cultural background and experiences inform her case plan. They prioritize including her voice in discussions about her child’s support, recognizing that her input is essential to developing effective interventions. This inclusion extends to all families they serve, ensuring that care is culturally sensitive and responsive. - Collaboration:

During the reflective supervision meeting, the MDT collaborates on developing a comprehensive treatment strategy for the young mother and her child. They leverage their diverse expertise to ensure that the intervention plan addresses both developmental and emotional support needs. The team emphasizes the importance of collaborative practice, where all member’s insights are valued and utilized. - Empowerment:

The focus on empowerment involves enhancing understanding and support within the organization to strengthen cultural humility among leaders. The MDT discusses the importance of training for leadership on cultural competence and implicit bias, recognizing that leaders play a crucial role in shaping the organizational culture. They highlight the significance of the parallel process, where the dynamics within the team reflect the supportive practices, they wish to implement with families. By empowering team members to advocate for necessary changes, they build a more responsive and inclusive organization.

Table 2. Application of the JUSTICE Framework.

Outcome

By fully integrating the JUSTICE framework, the MDT experiences significant improvements in how they support families from marginalized backgrounds. The reflective supervision process, in particular, enables leadership to model vulnerability and inclusion, which encourages the entire team to adopt these values in their work. As leaders practice transparency and engage in difficult conversations about bias and power, the team is empowered to confront these issues openly. This leads to stronger relationships within the team and with the families they serve. The Palestinian mother, for example, receives more relevant and culturally sensitive support as a result of the team’s efforts to address their own biases and lean into discomfort. Overall, the framework enhances the team’s emotional connection, deepens understanding, and creates a more equitable and inclusive approach to family support. Leaders’ engagement in safe and brave spaces also ensures that the team continues to grow in its ability to serve diverse populations with empathy, authenticity, and fairness.

Co-Creating Authentic Relationships in Supervision

Building authentic relationships in reflective supervision demands a bi-directional process, where both leaders and supervisees grow together through openness and trust. Using the JUSTICE framework, supervisors can model vulnerability through Justice and Transparency, creating fairness and equality in their interactions (Sen, 2009). By acknowledging discomfort and encouraging Inclusivity in Discomfort, supervisors and supervisees can engage in meaningful conversations, addressing power dynamics and shared emotions. This co-creation fosters Understanding and builds Relational Safety, a critical factor for healing, especially for those with trauma triggers (Brown, 2018). When leaders embrace vulnerability, they foster an environment where both parties can grow, learn, and heal through the relationship.

Relational safety is crucial because relationships can sometimes reignite past traumas. Supervisors using the JUSTICE framework can help break this cycle by practicing Empathy and Connecting with Emotions. This compassionate approach strengthens the bond between supervisor and supervisee, transforming potentially harmful interactions into opportunities for growth and understanding. By intentionally creating safe and brave spaces, supervisors provide a healing environment where vulnerability is seen as a strength and relationships become vehicles for deep transformation and impactful change.

Addressing Systemic Barriers in Reflective Supervision

Systemic barriers in reflective supervision often stem from organizational ghosts—the lingering effects of historical trauma, unresolved conflicts, and power imbalances that shape organizational culture (Peak & Kronenberg, 2010). These ghosts leave behind remnants of pain that hinder system change and perpetuate inequities. The JUSTICE framework helps leaders confront these barriers by promoting Justice, Understanding, and Transparency (Rawls, 1971). By addressing these organizational traumas, leaders can foster relational safety, allowing both supervisors and supervisees to engage in growth and healing.

Through the JUSTICE framework, leaders are encouraged to lean into discomfort, using Inclusivity and Empathy to address the lingering effects of systemic trauma. By acknowledging these ghosts, reflective supervision becomes a tool for healing, where historical inequities are actively dismantled. This approach promotes leadership growth and organizational transformation, creating an environment where equity and inclusion are prioritized (Brown, 2018). By integrating justice-oriented principles, leaders can ensure sustainable change that heals both individuals and systems.

The Global Impact: Reflective Supervision Across Borders

The global relevance of reflective supervision is becoming increasingly significant, as leaders and supervisors across borders recognize the importance of creating spaces for vulnerability, growth, and healing. In diverse cultural contexts, the JUSTICE framework serves as an adaptable tool, allowing leaders to foster fairness, empathy, and inclusivity while addressing systemic inequities in supervision (Nussbaum, 2011). This approach encourages leaders to lean into discomfort and confront the power dynamics that exist within their unique cultural landscapes, enabling true transformation across borders.

The JUSTICE framework is particularly impactful because it transcends cultural differences, offering a universally adaptable model for relational safety and organizational growth. By focusing on principles like Justice, Transparency, and Inclusivity, leaders can create environments where trust and understanding flourish, regardless of the specific cultural challenges they face. This adaptability ensures that reflective supervision remains relevant across diverse cultural contexts, fostering equity and growth in leadership practices worldwide (Brown, 2018).

Conclusion

Moving Forward with Courage and Commitment

In Embracing Discomfort: Empowering Supervisors and Leaders Globally through the JUSTICE Framework in Reflective Supervision, centering the JUSTICE framework allows leaders and supervisors to lead with vulnerability, creating an atmosphere of trust and emotional safety. By doing so, they foster growth not only within themselves but also within their teams, promoting developmental and organizational progress. This approach builds healthy, lasting relational dynamics, supporting both individual and collective success. The framework enables leaders to cultivate environments where genuine relationships flourish, leading to impactful, long-term organizational change (Nussbaum, 2011; Brown, 2018).

References

Bennett, M. J., Gardner, D., & Stewart, R. (2020). Creating brave spaces: The role of leadership in fostering inclusivity and trust in organizations. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 27(3), 321-334.

Brown, B. (2018). Dare to lead: Brave work. Tough conversations. Whole hearts. Random House.

Feniger-Schaal, R., & Oppenheim, D. (2020). Reflective Supervision in a Global Context. Infant Mental Health Journal, 41(4), 431-444.

Gilkerson, L., & Imberger, J. (2016). A framework for reflective supervision: Building relationships, sustaining hope. Zero to Three Journal, 36(2), 22-29.

Hutchinson, H. (2023). The Justice Framework, The Journey Institute.

Nussbaum, M. C. (2011). Creating capabilities: The human development approach. Harvard University Press.

Peak, A. & Kronenberg, M. (2010). Organizational ghosts: How the past impacts the present. Organizational Dynamics Journal.

Rawls, J. (1971). A theory of justice. Harvard University Press.

Sen, A. (2009). The idea of justice. Harvard University Press

Sue, D. W., Capodilupo, C. M., Torino, G. C., Bucceri, J. M., Holder, A. M. B., Nadal, K. L., & Esquilin, M. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271-286.

Watson, T., & Gatti, S. (2012). Power and Vulnerability in Reflective Supervision: A Global Perspective. Journal of Reflective Practice, 10(2), 215-228.

Authors

Hutchinson, Harleen,

President of the Florida Association for Infant Mental Health,

Executive Director of The Journey Institute, Inc

United States

Dr. Harleen Hutchinson is the President of the Florida Association for Infant Mental Health and the Executive Director of The Journey Institute, Inc. She is a highly regarded Clinical Mentor, endorsed in Infant Mental Health, with over 25 years of experience working with young children and families. Dr. Hutchinson specializes in supporting early relational health and addressing social determinants of health, particularly for BIPOC mothers. Her expertise in reflective supervision and consultation extends locally, nationally, and internationally, providing critical guidance to professionals who work with children from birth to five years old. Through her work, Dr. Hutchinson strengthens the capacity of professionals across systems, ensuring they are equipped to nurture the emotional well-being of young children. Her leadership in early childhood development, trauma-informed care, and equity has made her a pivotal figure in promoting healthy, resilient communities for families, especially in marginalized populations.