Funding: Health Research Council of New Zealand

Ethics Approval: Approved by the Auckland University of Technology Ethics Committee (AUTEC) on 10 January 2018, AUTEC Reference number 17/363.

Background: This research, beginning with doctoral work in 2015, developed the first comprehensive Indigenous alternative to Western attachment theory. When this work began, Indigenous perspectives on attachment were virtually absent from the literature. The Tūhono framework has since influenced emerging international Indigenous attachment scholarship.

Objective: To investigate Māori perspectives on secure attachment relationships and develop a culturally grounded framework for transforming infant mental health practice through Indigenous knowledge systems.

Methods: Kaupapa Māori research methodology was utilised with 65 participants across Aotearoa New Zealand, employing culturally appropriate qualitative methods and the Te-āta-tu Pūrākau analytical framework. Participants included kaumātua, key informants, and whānau (family) constellations representing diverse family systems.

Results: Five interconnected themes emerged: (1) Whakapapa as a continual thread connecting children across generations; (2) Te reo Māori as a healing language; (3) Whānau constellated caregiving systems; (4) Ūkaipō-Kainga as nurturing environments; (5) Mahi Tūhono and Mahi Pāmamae as trauma-centered healing approaches.

Conclusions: The Tūhono framework offers a transformative paradigm that has influenced international Indigenous attachment scholarship. Recent studies reaching similar conclusions validate this pioneering work’s foundational contributions to decolonising infant mental health practice globally.

Keywords: Tūhono, Indigenous attachment, Kaupapa Māori, whānau (family), decolonising practice, infant mental health

Introduction

When this research began in 2015, Indigenous children worldwide faced disproportionate removal from families, yet Indigenous perspectives on attachment were virtually absent from academic literature. In Aotearoa New Zealand, recent government reporting has highlighted the disproportionate representation of Māori children in Aotearoa New Zealand’s state care system, along with troubling evidence of abuse. According to the Independent Children’s Monitor (2024), Māori comprise roughly one-third of the child population yet make up two-thirds of those in state care and three-quarters of youth justice placements. In 2023, 9 per 1,000 tamariki Māori were in care, compared to 2 per 1,000 non-Māori, with Māori children comprising 50% of all reports of concern to the Oranga Tamariki — Ministry for Children. The Disparities and Disproportionality Report by Oranga Tamariki (2023) further found that 82 out of every 1,000 tamariki Māori were reported to Oranga Tamariki, compared to 24 per 1,000 non-Māori.

This pattern of overrepresentation has persisted for more than a decade. Findings from the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care (2024) revealed that Māori survivors reported higher levels of physical, psychological, and cultural abuse than other ethnic groups. Tamariki Māori were more likely to be institutionalised, targeted with racism, and denied access to te reo, tikanga, and whānau connections—factors contributing to intergenerational trauma and Treaty breaches.

Te Tiriti o Waitangi – The Treaty of Waitangi

Te Tiriti o Waitangi, signed in 1840 between Māori rangatira (chiefs) and representatives of the British Crown, is widely acknowledged as the founding document of Aotearoa New Zealand. It was intended to establish a mutually respectful relationship, where Māori would retain authority (tino rangatiratanga) over their lands, people, and tāonga (treasures), while allowing the Crown to exercise governance over its own people.

Two versions were signed—one in English, and one in te reo Māori—but the meanings diverge significantly. The Māori text affirms Māori sovereignty and self-determination, while the English version has often been interpreted as a cession of sovereignty to the Crown. This dissonance has created decades of conflict and ongoing efforts to reconcile historical and contemporary breaches.

Rather than framing obligations solely through Crown-derived principles like partnership, protection, and participation, many Māori scholars and communities advocate a return to the original intent and authority of Te Tiriti grounded in mana motuhake (autonomy), honouring whakapapa and upholding tikanga Māori (Māori protocols). These perspectives emphasise Māori-led approaches to wellbeing, justice, and care. In the context of child and adolescent mental health, recognising the place of Te Tiriti means more than cultural inclusion—it calls for structural transformation, where Māori knowledge systems, healing practices, and self-determination are central rather than supplementary.

Research Genesis

This research emerged from doctoral work in 2015 investigating relationship dynamics between Māori mothers and their tamariki when exposed to partner violence (Hall, 2015). That foundational study revealed the inadequacy of Western attachment frameworks for understanding Indigenous experiences, establishing an urgent need for culturally grounded alternatives. The concept of tūhono—meaning to connect, attach, or bond—offered a foundation for exploring Māori perspectives on secure relationships extending beyond individual parent-child dyads.

Study Aims

This study aimed to: (1) investigate Māori perspectives on secure attachment relationships; (2) identify traditional and contemporary practices supporting healing; (3) develop a culturally grounded framework positioning Indigenous knowledge as primary; and (4) contribute to global Indigenous movements toward decolonising child welfare systems. The research addresses three critical gaps: lack of Indigenous theoretical frameworks, insufficient understanding of traditional practices promoting secure relationships, and absence of community-led models positioning Indigenous communities as authorities over their children’s wellbeing rather than subjects of external intervention. LeVine (1974) understood the important links between cultural values, and the influence of child-rearing practices, indeed Ainsworth was critical of the over reliance on the Strange Situation laboratory investigations into attachment noting the lack of fieldwork research (Ainsworth & Marvin, 1995).

Research Agenda – Epistemic Sovereignty

Centering Indigenous research methodologies is an act of resistance; it challenges colonial frameworks, asserts epistemic sovereignty, and uplifts knowledge systems that have sustained Indigenous peoples despite centuries of erasure. Framed as a positive assertion of epistemic sovereignty, resistance through Indigenous research methodologies disrupts colonial knowledge hierarchies and reclaims space for relational, place-based ways of knowing (Cunneen et al., 2017). Epistemic justice calls for the dismantling of entrenched hierarchies that privilege Western epistemologies as the default standard of legitimate knowledge. This dominance has historically marginalised Indigenous, Black, and Global South ways of knowing, often relegating them to the periphery of academic discourse. As Maleku (2025) argues, achieving epistemic justice requires more than inclusion; it demands a fundamental reorientation of knowledge production that centres pluralism, relationality, and community-rooted epistemologies. Resistance, in this context, becomes a generative force: a deliberate pushback against epistemic dominance that reclaims space for diverse intellectual traditions and affirms the right of all peoples to define, validate, and transmit their own knowledge systems. Bishop’s (2010) assertion that Kaupapa Māori research is controlled by Māori for the empowerment of Māori aligns with the foundational principles articulated in Smith’s (2012) Decolonizing Methodologies.

Methods

Kaupapa Māori Methodology

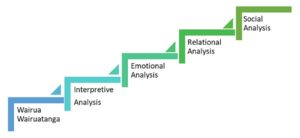

This research employed Kaupapa Māori methodology, prioritising Indigenous knowledge systems and community self-determination (Smith, 2012). A Pūrākau narrative inquiry data collection method was used in the research (Lee, 2009). Central to this framework is whakapapa—genealogical connections linking individuals to ancestors, descendants, and natural world. The methodology ensures consistency with a Māori worldview and enables whānau to identify key family members in the care-giving system (See Mikahere-Hall, 2017, 2019). Te-āta-tu Pūrākau, a five-step Indigenous analytical method was utilised in the research, which provided the analysis framework (see Mikahere-Hall, 2019). This method captures the narrator or storytellers’ ability to move through different aspects of their pūrākau (narrative), where analysis involves a search for themes under groupings: (1) Social circumstances; (2) Relational dynamics; (3) Emotional content. Two further steps were included (4) Interpretive analysis and (5) Wairua or Wairuatanga (Spiritual content). Pūrākau are traditional Māori oral histories that carry cultural knowledge and wisdom. Life events both past and present, relationships and connections to people and places are deeply interconnected. Pūrākau have traditionally served to transmit histories and experiences while conveying nuanced meanings that Māori whānau draw upon for guidance and understanding.

Pūrākau are well-established as both a narrative inquiry method in research and an educational pedagogy among Māori Indigenous scholars in Aotearoa New Zealand (Pouwhare, 2023; McLachlan et al., 2017; Lee, 2009). As a research methodology, Pūrākau and Te āta tu Pūrākau are complimentary and represents a Kaupapa Māori approach that captures participants’ narratives in culturally appropriate ways, increasingly utilised in educational and social services contexts. This methodology serves as an expression of decolonising practice, reclaiming Indigenous oral accounts of experiences and perceptions as a legitimate form of inquiry that counters colonial misrepresentations that have historically portrayed these narratives as simple mythology or homogenised accounts.

Researcher Positionality

All members of the research team identify as Indigenous Māori, bringing lived experience and cultural understanding that fundamentally shaped our research design. Our positioning as Indigenous researchers means we approach this work not as external observers, but as cultural insiders with deep connections to the knowledge systems, worldviews, and communities central to this research. This insider positioning enables us to engage authentically with Kaupapa Māori methodology and methods recognising the spiritual, relational, and cultural dimensions embedded within these approaches as legitimate and essential components of knowledge creation. Our shared Indigenous identity provides us with cultural competency to interpret nuanced meanings within participants’ narratives and to understand the broader sociocultural and sociopolitical contexts that inform their experiences such as the on-going impacts of colonisation.

As Indigenous researchers, we acknowledge our responsibility to conduct research in ways that honour our cultural protocols, benefit our communities, and contribute to the broader project of Indigenous knowledge sovereignty. We recognise that our cultural positioning both privileges our understanding of Indigenous ways of knowing and creates accountability to ensure this research serves Indigenous peoples’ interests.

Our collective Indigenous identity also means we bring particular sensitivities to issues of colonisation, cultural misrepresentation, and the importance of self-determination in research processes. This positioning informs our commitment to Kaupapa Māori principles and our resistance to research approaches that would extract knowledge from our communities without reciprocal benefit.

We acknowledge that within our Indigenous identities, we each bring unique tribal affiliations, personal experiences, and professional backgrounds that further shape our individual and collective perspectives on the research.

Participant Recruitment

Whanaungatanga (extended relationships) served as recruitment method, utilising existing networks to engage participants while maintaining cultural accountability.

Participants and Data Collection

Sixty-five participants were involved across three domains: kaumātua (elders, n=6), key informants (n=6), and whānau constellations (n=25 groups). Whānau represented diverse contemporary configurations including mixed-ethnicity partnerships, single parents, same-sex couples, whāngai arrangements, whānau hauā (disability whānau), and grandparents raising mokopuna. Pūrākau (Mikahere-Hall, 2019; Lee, 2009; Hall, 2015) provided the primary data collection method, gathering family and traditional knowledge through culturally appropriate narratives. All research participant data was recorded and transcribed for data analysis purposes. Pūrākau are central to the research design and as Mehl-Madrona (2007) observes, “What we have are collections of stories that make sense to members of the cultures who tell them” (p. 5). This understanding is fundamental to Kaupapa Māori-driven research, which is purposefully undertaken by Māori with Māori participants to generate culturally grounded, ‘insider’ (Lee-Morgan, 2019) oriented insights. This approach eliminates the problematic outsider perspectives and misinterpretations that can arise when research is conducted without appropriate cultural understanding and positioning. Smith’s (2012) cautionary explanation attests to the importance of getting the story or stories right, generating knowledge from the inside for solutions orientated outward for community benefit. As Lee-Morgan (2019) suggests engaging with pūrākau from the “inside-out” (p. 151)

Data Analysis

The analysis method Te-āta-tu Pūrākau was developed by Hall (2015) as a systematic and philosophical approach to support the analysis of Pūrākau inquiry. Te-āta-tu Pūrākau shares similarities with thematic analysis where themes emerging from data help identify key insights however it differs fundamentally in its ontological foundation. Unlike Western research paradigms that typically focus on observable phenomena, Pūrākau methodology recognises spiritual insights, ancestral wisdom, and intuitive understanding as valid sources of knowledge alongside empirical data. This worldview acknowledges transcendent, intuitive, and esoteric knowledge as existing and as a naturally occurring accessible human function. The analysis recognises spiritual beliefs as intrinsic to the narrator and therefore preserving their integrity rather than reducing them to secular interpretations.

The analysis process identified recurring patterns of meaning within the Pūrākau and coded these within the four specific domains detailed in the five step Te-āta-tu Pūrākau analysis method (see Figure 1.). Beginning with the Social Analysis step working down to step five with the purpose of delving deeper into the data. The fourth step recognises the researcher as an active participant and receiver of the pūrākau, acknowledging that receiving these narratives involves active sense-making processes. This step focuses on the researcher’s interpretive analysis, examining how meaning is constructed through the interaction between the narrative and the researcher’s understanding. The fifth step observes how spiritual beliefs are engaged, considering how foundational worldviews and cultural beliefs contribute to the meaning-making processes. Te-āta-tu-Pūrākau organises the raw narrative data into five interconnected related domains to produce the foundational themes and sub-themes.

Ethical Framework

Ethical approval was granted following important Health Research Council Māori ethical guidelines and research principles as set out in Te Ara Tika (Hudson et al., 2010). The principles helped inform and guide participant recruitment and data collection processes in an acceptable manner from both cultural and health research perspectives. The principles are values-based and embody manaakitanga (care) to guide the quality and structure of processes from which engagement between researcher and research participants unfolds (Mikahere-Hall, 2019).

Safe tikanga values and practices guide the nature in which researchers and research participants engage in the research study. The guiding Māori principles include tika (correctness), pono (integrity) and aroha (compassion). Rangatiratanga (leadership), manaakitanga (respectful regard), kaitiakitanga (guardianship) and wairuatanga (spirituality) are also embraced as respected Māori ethical principles fundamental to this Kaupapa Māori research project (Mikahere-Hall, 2019).

Results

Under each of the five overarching themes, a number of sub-themes were identified. These sub-themes provided further nuance and insight into how these core ideas were enacted, understood, and experienced in diverse whānau contexts. For example, within Whānau constellated caregiving systems, sub-themes reflected varied caregiving roles taken up by extended whānau members and the fluidity of relational responsibilities. Similarly, Mahi Tūhono and Mahi Pāmamae included sub-themes such as narrative healing, Te Oro Tapu (sacred prayer song), reconnection with whakapapa, and expressions of intergenerational resilience. Together, these themes and sub-themes formed an integrated framework that highlights Māori ways of knowing, being, attaching and healing in the context of child wellbeing and protection. While a number of sub-themes emerged within each category, this article presents only the overarching themes due to word count constraints. Sub-theme analysis will be explored further in future work due for publication in 2025.

Theme 1: Whakapapa

Whakapapa emerged as the foundational connection linking children to ancestral past, present relationships, and future generations. Unlike Western attachment’s focus on individual relationships, whakapapa provides inherent belonging transcending circumstances. As stated by one kaumatua (elder):

There is only one of me there is only one of you but we descend from and we have decadency. So how to remain as mātua tupuna (ancestors) do we extend and expand that. We are not talking one generation here we are talking thousands of generations nē (isn’t it). It is the preservation of our ira (gene).

This kaumatua spoke of whakapapa as central to the rituals concerning death, where making ancestral connections to the deceased are recited for the benefit of the living. Acknowledging the important contribution the deceased has made to the continuity of whānau and the footprints left behind in the form of tamariki (children), mokopuna (grandchildren) and the potentiality for future generations to quote:

“Those gatherings are important exposure to your understanding of your evermore whakapapa (genealogy)”

This genealogical framework ensures children’s worth exists independently of individual relationships, providing security through collective identity rather than dyadic bonds. One female kaumātua explained:

You could say that it takes a valley to bring up a child and it can go from the bottom of that road; …to the end of that road. As the children are growing in that valley they have always got someone that’s watching out for them, being protective of them. So, by the time someone gets from the beginning to the end of that road everybody’s looking, watching and thinking “Oh yeah there goes P—he’s okay he’s safe, he’s going home or he’s going the other way, or he’s going wherever he’s going. So, the protection [of the child] was the whole valley being involved.”

Whakapapa challenges Western individualistic assumptions by positioning collective responsibility as fundamental to child development.

Theme 2: Te Reo Māori (The Māori Language) as a Healing Language

Te reo Māori emerged as a transformative healing language, shifting from deficit-based terminology to concepts promoting connection. Participants consistently described how English language pathologised their experiences while te reo Māori offered healing alternatives. When explaining the importance of the Māori language several kaumatua talked about the spiritual ethos of the language and the importance of karakia (incantations/prayer) mihimihi (acknowledgements).

It is hard for us to hear sometimes, when you use our reo [language] it is not harsh it doesn’t talk about disorders it thinks about all things having connection and relationships be it good or be it bad

This linguistic transformation challenges Western diagnostic frameworks that label Indigenous children and families as problematic. The shift from “attachment disorders” to “tūhono” (connection) and “tūhonotanga” (connectedness) reframes challenges as opportunities for strengthening bonds.

Theme 3: Whānau Constellated Caregiving

Whānau constellated caregiving systems encompassed grandparents, siblings, and extended networks beyond nuclear family models. This collective approach distributes caregiving responsibility across multiple relationships and affirms the centrality of communal care in Māori child-rearing practices.

I think that really ideally, we want all our Māori children to grow up with secure identities, with knowing who they are and to have those connections as wide as possible…that buffer of whānau around them.

This quote speaks to the importance of identity and belonging as outcomes of expansive whānau support. The metaphor of a “buffer” suggests both protection and emotional grounding, highlighting how secure cultural identity is shaped through multiple, relational threads.

The belief is in them; it is in them. A lot of people think I want to go and do this or I want to go here, but no, you have to believe in your children and the moko [abbreviation for grandchild] you are there for them. It’s like We! We are going to do this; it is not an ‘I’ thing. We are a very tight family.

This expression of shared belief and collective action affirms how caregiving is framed not as an individual task, but as a coordinated whānau endeavour. The emphasis on “we” over “I” underscores a deep interdependence and a values-based commitment to uplift tamariki as a shared responsibility. One key informant described:

The task is not for every hand, yet no hand at all but for many hearts to gather around the tamaiti, so that in the giving, both the tamaiti and the village grow.

This whakataukī (proverb) inspired reflection beautifully captures the reciprocity embedded in caregiving: as tamariki are nurtured by the collective, the collective itself is enriched. It illustrates a philosophy where care is relational, continuous, and spiritually grounding. Together, these insights reveal whānau constellated caregiving as a dynamic and culturally grounded model, in which caregiving is not only about protection, but also about empowering identity, collective resilience, and the growth of the entire community.

Theme 4: Ūkaipō-Kainga as Nurturing Environments

Ūkaipō-Kainga represents nurturing environments including spatial and spiritual connections to ancestral lands. Security emerges from place-based connections extending beyond human relationships.

In terms of the bond or attachment, in most cases, whānau, I think are awesome, because breast feeding is something that they chose to do,…you know it’s the intergenerational thing, we are breast feeders, we are ūkaipō [mother’s sustenance], you know ūkaipō how we all connect to Papatūānuku [mother earth], this connection to our tūpuna whenua [ancestral land]. It reminds us to nurture our babies, ourselves and our environment.

This theme challenges Western attachment’s focus on human relationships by incorporating environmental and spiritual dimensions of security. Connection to place provides grounding and identity that supports attachment relationships.

Theme 5: Mahi Tūhono-Mahi Pāmamae

Mahi Tūhono-Mahi Pāmamae integrates trauma-centered healing approaches including waiata (song), oriori (prayer-song), and aroha as intentional healing behaviors. As one of our guiding research elders promoted in her life’s work “We have to sing the soul back into being” Hinewirangi Kohu-Morgan (10/12/1947 – 15/02/2023). Traditional practices become therapeutic interventions promoting security, with a key informant research participant stating:

Aroha, is always part of healing, it is intentional life-giving behaviour, the cohesive bond, when this is missing our babies our mokopuna learn to know the nothingness

This integration of cultural practices with trauma healing demonstrates how Indigenous approaches address both individual and collective healing needs, providing alternatives to Western therapeutic interventions.

Discussion

Western attachment theory, whilst valuable in many contexts, emerged from particular cultural assumptions about nuclear family structures, maternal responsibility, and individual psychological development (Keller, 2017; Vicedo, 2017). When applied universally without cultural adaptation, these frameworks can pathologise Indigenous caregiving practices and justify ongoing colonial interventions that separate children from their communities (Choate et al., 2019). The predominance of Western theories in infant mental health practice represents what Indigenous scholars identify as epistemic injustice—the systematic devaluation of Indigenous knowledge systems in favour of Western academic paradigms (Smith, 2012). The Tūhono research study is not a dismissal of the important infant-mother relationship; however, it is a shift toward the whānau and the key members that make up this constellation of people there to support, nurture and grow the expanding whānau and to protect the mother, infant child and children.

International Validation

The Tūhono framework’s core insights have been validated by recent international scholarship. Waters et al. (2024) reached remarkably similar conclusions about expanding beyond dyadic relationships, while Wright et al. (2025) identified epistemic violence in attachment theory applications—issues the Tūhono framework addressed previously. This convergence may suggest the framework’s foundational influence on emerging Indigenous attachment scholarship and it is imperative that this work continues to develop. The convergence of conclusions demonstrates the framework’s prescient identification of Western attachment theory’s limitations for Indigenous populations.

Theoretical Contributions

The Tūhono framework offers three key theoretical contributions: First, it positions Indigenous knowledge as primary rather than supplementary to Western frameworks. Second, it demonstrates how cultural practices function as therapeutic interventions. Third, it establishes community-led models positioning Indigenous communities as authorities over their children’s wellbeing rather than subjects of external intervention.

Practice Implications

The framework provides immediate applications for transforming infant mental health practice. Assessment approaches must incorporate whakapapa connections, whānau constellation caregiving, and place-based relationships. Intervention strategies should integrate traditional healing practices and prioritise cultural language over diagnostic terminology. Training programmes require fundamental restructuring to centre Indigenous knowledge systems. This includes understanding collective caregiving models, recognising cultural practices as therapeutic interventions, and developing greater cultural understanding and responsiveness in Indigenous worldviews to increase safety. Child welfare systems need systemic transformation to honour Indigenous ways of understanding secure relationships while addressing contemporary challenges.

Conclusion

The Tūhono framework, developed through a pioneering decade-long research investigation has established Indigenous attachment research as a legitimate field and influenced international scholarship. Its validation through recent international studies reaching similar conclusions demonstrates the framework’s transformative potential for infant mental health practice globally.

The Tūhono framework offers essential foundations for decolonising child welfare systems while revitalising traditional practices promoting secure relationships and healing from intergenerational trauma. Future research should focus on implementation strategies, cross-cultural applications, and measuring outcomes using Indigenous evaluation frameworks. The framework’s influence on emerging scholarship indicates growing recognition that Indigenous knowledge systems provide sophisticated, complete alternatives to Western paradigms. This work contributes to global Indigenous movements towards epistemic justice and community self-determination in child welfare.

Glossary – Māori Terms

| 1. Aroha | caring, affectionate, compassion |

| 2. Aotearoa | Māori name for the country known as New Zealand |

| 3. Iwi | extended kinship group, tribe, nation, people, nationality |

| 4. Kāinga | (as part of Ūkaipō-Kāinga) home, settlement, village |

| 5. Karakia | prayer, to recite prayer chant, incantation ritual |

| 6. Kaumātua | elder, elderly man, elderly woman, person of status in the family |

| 7. Kaupapa Māori | Māori approach, Māori topic, Māori customary practice, Māori institution, Māori agenda, Māori principles, Māori ideology – a philosophical doctrine |

| 8. Mahi | to work, do, perform, make, accomplish, practise |

| 9. Mahi Pāmamae | intentional work focus on healing painful experiences |

| 10. Mahi Tūhono | intentional work focus on attachments and connections |

| 11. Mana motuhake | autonomy, self-determination, independence, sovereignty, control over one’s own destiny |

| 12. Manaakitanga | generosity, kindness, support |

| 13. Mātua tupuna | mātua -grown-up, adult, parental – tupuna -ancestor, grandparent |

| 14. Mihi / Mihimihi | to greet, to acknowledge |

| 15. Moko | grandchild abbreviation for mokopuna |

| 16. Mokopuna | to be a grandchild, a descendant |

| 17. Oriori | prayer song, lullaby |

| 18. Pāmamae | traumatic, upsetting, distressing, painful, to feel hurt, trauma |

| 19. Papatūānuku | earth mother, primordial mother |

| 20. Pono | be true, valid, honest, genuine, sincere |

| 21. Pūrākau | narrative, storytelling |

| 22. Rangatahi | young person, adolescent, youth |

| 23. Rangatira | to be of high rank, leader |

| 24. Rangatiratanga | chieftainship, right to exercise authority, chiefly autonomy, leadership |

| 25. Reo | language, reference to Māori language (as part of te reo Māori) |

| 26. Tamariki | children |

| 27. Tamaiti | child |

| 28. Tāonga | treasure, gift, special gift |

| 29. Te Ara Tika | Correct path – relating to ethical conduct |

| 30. Te Oro Tapu | sacred sound |

| 31. Te reo Māori | The Māori language |

| 32. Te Tiriti o Waitangi | Treaty document signed in Waitangi in 1840 |

| 33. Te-āta-tu Pūrākau | the emerging dawning narrative used to metaphorically capture what arises from a state of unknown (darkness) into the light (clarity) because of narrative content analysis. Te āta (the dawn) tu (rise) Pūrākau (Pū -root source, rākau -tree) |

| 34. Tika | to be correct, true, upright, right, just, fair, accurate, appropriate |

| 35. Tikanga Māori | Māori protocols and values |

| 36. Tino rangatiratanga | esteemed authority, autonomy |

| 37. Tūhono | to join, attach, bond connect |

| 38. Tūhonotanga | attachment |

| 39. Tūpuna | ancestors, grandparents |

| 40. Tūpuna whenua | ancestral land |

| 41. Ūkaipō | mother, source of sustenance, nurture |

| 42. Ūkaipō-Kāinga | places of belonging, belonging to, home, nurturing |

| 43. Waiata | song, to sing |

| 44. Wairuatanga | spirituality, beliefs |

| 45. Whakapapa | table, lineage, recite genealogies, layers-upon layer as in generations |

| 46. Whakataukī | proverb |

| 47. Whāngai | to feed, nourish, bring up, foster, adopt, raise, nurture, rear |

| 48. Whānau | to be born, give birth, born into family, kinship group |

| 49. Whānau hauā | disabled whānau |

| 50. Whanaungatanga | relationship, kinship, sense of family connection – a relationship through shared experiences and working together which provides people with a sense of belonging |

References

Ainsworth, M. D. S., & Marvin, R. S. (1995). On the shaping of attachment theory and research: An interview with Mary D. S. Ainsworth (Fall 1994). Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 60(2-3), 3-21. https://doi.org/10.2307/1166181

Bishop, R. (2010). Effective teaching for Indigenous and minoritized students. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 7, 57-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.10.009

Choate, P. W., Kohler, T., Cloete, F., CrazyBull, B., Lindstrom, D., & Tatoulis, P. (2019). Rethinking Racine v Woods from a decolonising perspective: Challenging the applicability of attachment theory to Indigenous families involved with child protection. Canadian Journal of Law and Society, 34(1), 55–78. https://doi.org/10.1017/cls.2019.8

Cunneen, C., Rowe, S., & Tauri, J. M. (2017). Fracturing the colonial paradigm: Indigenous criminological perspectives. In A. Deckert & R. Sarre (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of Australian and New Zealand criminology, crime and justice (pp. 385-400). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-55747-2_26

Durie, M. (2006). Measuring Māori wellbeing [Paper presentation]. New Zealand Treasury Guest Lecture Series, Wellington, New Zealand.

Fricker, M. (2007). Epistemic injustice: Power and the ethics of knowing. Oxford University Press.

Hall, A. (2015). An indigenous Kaupapa Māori approach: Mother’s experiences of partner violence and the nurturing of affectional bonds with tamariki [Doctoral dissertation, Auckland University of Technology]. AUT Research Repository. https://hdl.handle.net/10292/9273

Hudson, M., Milne, M., Reynolds, P., Russell, K., & Smith, B. (2010). Te Ara Tika: Guidelines for Māori research ethics: A framework for researchers and ethics committee members. Health Research Council of New Zealand.

Independent Children’s Monitor. (2024). Te aroturuki i ngā whakahaere – Experiences of care in Aotearoa: Annual report 2024. https://www.icm.org.nz/reports/annual-report-2024/

Keller, H. (2017). Attachment. A pancultural need but a cultural construct. Current Opinion in Psychology, 15, 59–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.02.003

Keller, H., & Otto, H. (2009). The cultural socialization of emotion regulation during infancy. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 40(6), 996-1011. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022109348576

Lee-Morgan, J. B. J. (2019). Purakau from the inside-out: regenerating stories for cultural sustainability Decolonizing Research: Indigenous Storywork as Methodology.(eds JA Q’um Q’um Xiiem, JBJ Lee-Morgan and J. De Santolo) pp, 151-170.

Lee, J. (2009). Decolonising Māori narratives: Pūrākau as a method. MAI Review, 2, 1-12.

LeVine, R. A. (1974). Parental goals: A cross-cultural view. Teachers College Record, 76(2), 226-239.

McLachlan, A. D., Wirihana, R., & Huriwai, T. (2017). Whai tikanga: The application of a culturally relevant value centred approach. New Zealand Journal of Psychology (Online), 46(3), 46-54.

Maleku, A. (2025). Toward epistemic justice in social work research: (Re) imagining global knowledge production. The British Journal of Social Work, 55(2), 613-620. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcaf052

Mikahere-Hall, A. (2017). Constructing research from an indigenous Kaupapa Māori perspective: An example of decolonising research. Psychotherapy and Politics International, 15(3), e1428. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppi.1428

Mikahere-Hall, A. (2019). Tūhono Māori: A research study of attachment from an Indigenous Māori perspective. Ata: Journal of Psychotherapy Aotearoa New Zealand, 23(1), 61-76. https://doi.org/10.9791/ajpanz.2019.07

Oranga Tamariki. (2023). Report on disparities and disproportionality experienced by tamariki Māori in the care and protection system. https://www.orangatamariki.govt.nz/about-us/research/our-research/report-on-disparities-and-disproportionality-experienced-by-tamariki-maori/

Pouwhare, R., & Steagall, M. M. (2023). The Māui Narratives: from bowdlerisation, dislocation and infantilisation to veracity, a Māori practice-led approach. LINK PRAXIS, 1(1), 243-285.

oyal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care. (2024). He Purapura Ora, he Māra Tipu: From redress to puretumu torowhānui: Final report. https://www.abuseincare.org.nz

Smith, L. T. (2012). Decolonising methodologies: Research and Indigenous peoples (2nd ed.). Zed Books.

Statistics New Zealand. (2013). Te Kupenga 2013. http://archive.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/people_and_communities/maori/kei-te-pewhea-to-whanau-2012/new-approach-measuring-whanau.aspx

Vicedo, M. (2017). Putting attachment in its place: Disciplinary and cultural contexts. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 14(6), 684–699. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2017.1289918

Waters, S. F., Richardson, M., Mills, S. R., Marris, A., Harris, F., & Parker, M. (2024). Beyond attachment theory: Indigenous perspectives on the child–caregiver bond from a northwest tribal community. Child Development, 95(6), 1829-1844. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.14127

Wright, A., Gray, P., Selkirk, B., Hunt, C., & Wright, R. (2025). Attachment and the (mis)apprehension of Aboriginal children: Epistemic violence in child welfare interventions. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 32(2), 175-199. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2023.2280537

Authors

Mikahere-Hall, Alayne,

Taupua Waiora Research Centre, Auckland University of Technology,

Auckland, New Zealand

Wilson, Denise,

Taupua Waiora Research Centre, Auckland University of Technology,

Auckland, New Zealand

Pou, Pita Perehama,

Community Elder and Cultural Advisor,

Mangakahia, New Zealand