Key Words: Sankofa, Decolonization, Revitalization, Infant Mental Health History, Storytelling, Healing Justice

Funding: Irving Harris Foundation and the Academy of ZERO TO THREE Fellows

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

This manuscript has not been published elsewhere and is not under consideration by another journal.

Abstract

Conceptualizations of relational health, and infant mental health (IMH) have largely centered on the perspectives of White theorists and professionals. Often untold and less-centered less-central are the stories and contributions of culturally and racially diverse peoples who have supported, led, and labored on behalf of children and families for generations, despite harms perpetrated on their communities. The Sankofa IMH History Project supports revitalization by inviting diverse Storytellers to share stories and perspectives that are at risk of being left behind; recording them; and creating an archival resource for revitalizing relationships, IMH discourse, workforce development, practice, and policies. Symbology, QR codes, art, and reflective questions are used to prompt perspective-taking and collective reflection. Authors integrate text, oral tradition, spiritual, embodied, and cerebral wisdom, as means of engendering and transmitting knowledge, sustaining cultures, and informing revitalization and social change. The Sankofa Project is a love letter to our field.

Introduction

The Sankofa Infant Mental Health History Project (Sankofa Project) is an ongoing effort led by Indigo Cultural Center and co-held, co-dreamt, and co-created with the Steering Collective for the purpose of revisiting the history of infant mental health (IMH) and expanding our understanding of relational health.

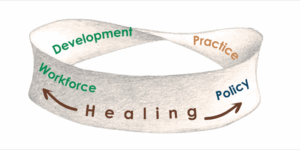

The conceptualization of IMH in the United States has largely centered on White theorists and professionals and infant-parent (usually mothers) dyads. Often untold and less-centered central are the stories and contributions of people and communities of color who have supported, led, and labored on behalf of young children and families for generations; the links between self, family, and community wellbeing that cultures worldwide have understood as inextricable; and how power and privilege have impacted the professional field’s development and directional focus through the decades. The Sankofa Project features the stories, wisdom, and contributions of IMH practitioners and scholars, illuminating the interconnected nature of workforce development, practice, and policy –much like the Möbius strip in Figure 1.

The Sankofa Project aims to support revitalization in IMH by inviting diverse storytellers to share stories at risk of being buried, left behind, unintegrated, or glossed over. Through recordings and archived resources, we aim to prompt pivots towards reimagining transformative relationships and possibility-creating (Ginwright, 2022). The Sankofa Project invites revitalizing ways of knowing and cultural practices –the cornerstones of replacing oppressive systems with systems that nurture healing and possibilities in communities. Figure 2. explains the significance of Sankofa.

History

The naissance and development of psychiatry 1650–1850 (Kendler et al., 2022), family studies in the early 1900s (Burgess, 2022), and pioneering work in IMH in the 1970’s (Policy Equity Group, 2023) coincided with European and United States imperialism and colonization (NIH, 2022). As language, cultures, and relationships were colonized often to the point of extinction, a knowledge vacuum about relational wellbeing was created. Not surprisingly, scholars and practitioners who saw the need to understand IMH health and develop evidence-based interventions in post-colonial societies were influenced by the colonialist, manifest destiny, eugenic, and White supremacist discourses of their times. We are deeply grateful to ancestors who persevered and kept language and knowledge about collective wellbeing alive through waves of genocide (Voce et al., 2021; NABS, 2020), so future generations might know, sustain, and pass forward healing practices rooted in abiding, relational principles that enabled cultures and communities to thrive for millennia (Richardson, et al., in press).

Key Concepts and Guiding Principles

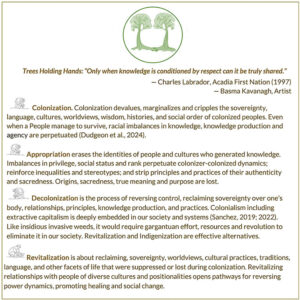

“While we can create good ideas and put them into words, there’s no assurance that these language-based symbolic representations will work for people who do not rely on verbal representation to express ideas. Sometimes, words, language- or number-based frames limit what is possible in terms of…mutual understanding between people (p. 4, Watanabe & Maharaj,2024). With this expansive approach in mind, the Sankofa Project’s Key Concepts are defined in Figure 4.

The Steering Collective is two years into its commitment to ongoing critical, reflective dialogue, discovery of diverse cultural guiding principles, and ways of living those principles. Combining principles and teachings from our own ancestors and those illuminated by Sankofa Project Storytellers, we hope to influence ways of being and being with among people who engage with the Project. QR Code 1, “Guiding Principles” features two elders revisiting principles that emerged while witnessing stories that inform the Sankofa Project, and engaging in critical reflective dialogue about the revitalization of IMH history. Along with centuries-long tradition of oral history, the video offers images and excerpts from their dialogue. We invite you to turn your phone camera on and scan the code below.

Colonization affects both colonizers and colonized in profound ways (Memmi, 1965). Revisiting what we “know” as professionals elicits many questions: What stories have not yet been illuminated about the history of our field? Are we working with fragmented truths that serve some, while harming others? What non-dominant sources of wisdom have been overlooked? What has been appropriated, exploited, and commodified, exacerbating harm? What did ancestors teach about relational and collective wellbeing? How might humility and resourcing community efforts (as opposed to outsider efforts) create new possibilities for healing in relationships and IMH workforce development, practice, and policy?

Land. Root. Seed. Culture. Community. Storytellers. Learners. (Methodology)

The need for revitalization has not been felt or dreamed by Indigo staff alone. There have been reverberations from many – particularly professionals of color – calling for change, truth-telling, and reckoning within our collective fields. Indigo partners with a small steering collective of IMH professionals who inspire and advise the design, process, and dissemination phases of the Sankofa Project. Each steering collective member brings a part of themselves, their stories, and their histories to how we see, think, and create together.

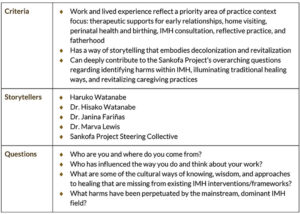

The Sankofa Project is a qualitative, emergent design endeavor featuring decolonizing methodology (Smith, 2005), on-going reflexivity, and theoretical sensitivity (Glazer, 1978). The primary means of collecting information are interviews with culturally and racially diverse IMH professionals. The Steering Collective began by generating a list of 20 people that could contribute to constructing a fuller history of IMH that centers the contributions of individuals and communities of color. Table 1 shows selection criteria, storytellers’ names, and examples of interview questions. In the end, we, the Steering Collective, also contributed reflections to the first Sankofa Project video, Part One: Land. Root. Seed. Culture. Community.

Table 1. Criteria. Storytellers. Questions.

At each interview, two to three members of the Steering Collective ask broad and exploratory questions to capture concepts and meanings. Interviewers explain their intent to reverse typical power dynamics by positioning interviewees as Storytellers, and themselves as witnesses and learners “at the feet of Storytellers” (Condon et al., 2022; Charlot-Swilley et al., 2024). Storytellers are asked to speak to the future, past, and present; their cultural context; IMH history; and their hopes for the field. Emergent themes are a basic building block of inductive, qualitative social science research. Themes are derived from the participants, not the researchers. Steering Collective members use a priori coding to analyze data generated in response to questions in interview guides and emergent coding for other data. (Charmaz, 2006; Saldaña, 2021).

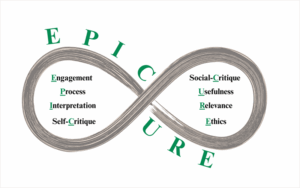

The EPICURE agenda (Stige et al, 2009) is used to decolonize and structure methods of investigation and generate accurate, credible, and useful results. Figure 5. shows connections among agenda elements.

The first part of the acronym –EPIC– addresses issues of process, highlighting the importance of reflective dialogue and self-critique in collaborative qualitative participatory action investigations. The second part – CURE– addresses the social implications of the work.

Implications: Integration, Innovation and Revitalization

The past lays the groundwork for things to come. What we know and understand about history influences who and how we are and what and how we do things in the present, and impacts the future. James Baldwin writes, “The great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us, are unconsciously controlled by it… History is literally present in all that we do” (Baldwin, 1965). He also offers, “If I love you, I have to make you conscious of the things you don’t see” (Baldwin, 1989).

Many current IMH policies – including funding, eligibility, programming, workforce development, etc. – are influenced by dominant versions of IMH history and practice. Yet, being in relationships is indigenous and endogenous to every human being. A historical accounting that acknowledges that our relatives and ancestors understood indigeneity and endogeneity in relationships informs a significantly different frame for IMH practice, policy, workforce development, and beyond.

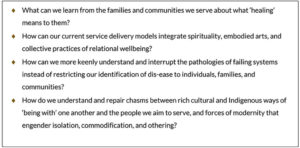

Practice. In Table 3, we offer reflective questions based on the Sankofa Project’s initial findings and themes, to invite readers to practice critical reflection and dialogue about what care looks and feels like as we co-journey with families and young children. Critical reflection and dialogue lead to healing justice-informed actions in service of ‘right’ relationships with families.

Table 3. Reflective Questions for Revitalizing Practice.

Policy. Major implications and recommendations that flow from this work relate to co-creating and revitalizing the infrastructure, networks, and conditions of our field. A revitalized IMH future must center and integrate an understanding of diversity, oppression, community assets, historical racial trauma, equity, and collective wellbeing (Irving Harris Foundation, 2028). We must acknowledge harms resulting from our past tendencies to not center the voices, traditions, ways of knowing, and worldviews of Indigenous, Black, Brown, Asian, and other People of Color. Elevating examples of policies informed by traditional wisdom and revitalizing ways of knowing will enable us to move beyond aspirations into realizing healing justice. Necessary, tangible movement forward must include sustained funding for the development of durable, cross-system infrastructure and workforce pathways that are based on expansive, expansive, anti-racist, revitalized, liberatory worldviews of IMH history.

Workforce Development includes the education and ongoing development of those who formally and informally support children and caregivers, prenatal to age five. Laying inclusive and revitalized historical groundwork in IMH, while partnering with and honoring the cultural wisdom and practices of communities, will support efforts to recruit, educate, train, and sustain a diversified workforce. The Sankofa Project’s efforts to document a re-storying of the history of the IMH field can contribute to supporting and growing the workforce into future generations and creating a more resonant and relevant IMH field for communities and families.

However, inclusion and revitalization only partially address the challenges and barriers to workforce development. Our accounting must acknowledge and address the systemic influence of historical and present-day enactments of power, privilege, marginalization, and oppression within individuals, relationships, and systems, as well as the mechanisms by which these are perpetuated and reproduced. Otherwise, it will be impossible to retain and sustain a diversified IMH workforce. Education and training efforts should align with expansive, revitalized worldviews – including approaches that extend understanding of relational contexts beyond self and other humans, to include earth, flora and fauna, spirit and divinity.

Such an expansive accounting invites and revitalizes buried or forgotten routes to healing and wellbeing not destroyed – impossible to destroy – because they live within relationships endogenous and indigenous to every human being. A diversified workforce needs a multitude of culturally rooted pathways to healing within their work, from secondary and vicarious trauma, and from societal and workplace harm and oppression.

Conclusion

It is possible to reach back and access cultural and indigenous routes to healing and wellbeing. It will involve changing not just what we do, but ‘how we be’ with one another, communities, families and children. Barbara Holmes inspires us, “There’s a point in our healing journey when we realize it is no longer personal. Our pain, the pain of our ancestry, is the pain of the world, and vice versa. Our healing is for humanity (2021). It will also involve looking at ourselves and our beloved field more fully and clearly –at both treasured contributions and harms. To be effective, decolonization and revitalization must be an authentic collective effort with commitment to sustained dialogue. We invite YOU, dear reader, to join us in going back, retrieving, studying, and passing on wisdom.

Our first video, The Sankofa Infant Mental Health History Project, Part One: Land. Root. Seed. Culture. Community, will be released in the fall of 2025. QR code 2 is a link to its webpage.

References

Baldwin, J. (1965, August). The White Man’s Guild. Ebony, XX No. 10, 47.

Baldwin, J. (1989). Conversations with James Baldwin. University Press of Mississippi, 156.

Burgess, N.J. (2022) Why Family Science? Because it shows us how families can thrive. NCFR website https://www.ncfr.org/about/what-family-science/why-family-science-cossa

Charlot-Swilley, D., Thomas, K., Mondi, C., Willis, D.W., & Condon, M-C. (2024). A Holistic Approach to Early Relational Health: Cultivating Culture, Diversity, and Equity. Journal of Environmental Research & Public Health, 21(5), 563.

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage.

Condon, M-C., Charlot-Swilley, D., & Rahman, T. (2022). At the feet of storytellers: Equity in early relational health conversations. Infant Mental Health Journal, 1–20.

Ginwright, S.A. (2022). The four pivots: Reimagining Justice, Reimagining Ourselves. North Atlantic Books.

Dudgeon (Bardi), P., Milroy (Palyku), H., Selkirk (Noongar), B., Wright (Nunga), A., Regan (Wongi and Noongar), K., Kashyap, S., Agung-Igusti, R., Alexi, J., Bray, A., Chan, J., Chang, E.P., Cheuk, S.W.G., Collova, J., Derry, K. and Gibson (Gamilaraay), C. (2024). Decolonization, Indigenous health research and Indigenous authorship: sharing our teams’ principles and practices. Medical Journal of Australia, 221: 578-586.

Holmes, B.A. (2021). Crisis Contemplation: Healing the Wounded Village.

Irving Harris Foundation. (2028). Diversity-informed Tenets for work with infants, children and families (available in English). Principios Informados en la diversidad para trabajar con bebés, niños, niñas y familias (y en Español) Date accessed: July 13, 2025.

Kendler, K.S., Tabb, K., & Wright, J. (2022). The Emergence of Psychiatry: 1650–1850 American Journal of Psychiatry (179).

Labrador, C. (1997). Trees holding hands. Oral Presentation. http://www.integrativescience.ca/Principles/TreesHoldingHands/

Memmi, A. (2016). The colonizer and the colonized (H. Greenfeld, Trans.). Souvenir Press.

National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition (NABS) (2020). Healing Voices: A Primer on American Indian and Alaska Native Boarding Schools in the U.S. 2nd Edition. https://boardingschoolhealing.org/education/us-indian-boarding-school-history/

NIH National Genome Project. (2022). Eugenics and Scientific Racism. NIH website https://www.genome.gov/about-genomics/fact-sheets/Eugenics-and-Scientific-Racism

Policy Equity Group. (2023). Thinking bigger to transform Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health. https://policyequity.com/thinking-bigger-to-transform-infant-and-early-childhood-mental-health/

Saldaña, J. (2021). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (4th ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd.

Sanchez, N. (2019). TED Talk: Decolonization is for everyone. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QP9x1NnCWNY

Sanchez, N. (2022). TED Talk: Re-thinking who we are through a decolonizing lens: Sisa Quispe. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zgdzdV-l3EY

Stige B, Malterud K, Midtgarden T. (2021). Toward an Agenda for Evaluation of Qualitative Research. Qualitative Health Research. 2009. 19(10):1504-1516.

Voce, A., Cecco, L., & Michael, C. Cultural genocide: the shameful history of Canada’s residential schools – mapped. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/ng-interactive/2021/sep/06/canada-residential-schools-indigenous-children-cultural-genocide-map

Watanabe, H., & Maharaj, S. (2024). Discovering the meaning of ‘Amae’ and its use in Infant Mental Health work and Beyond. Perspectives in IMH. 32 (1).

Authors

Sankofa Project Steering Collective:

Condon, Marie-Céleste

Reflective Consultant & Researcher,

United States

Subramaniam, Aditi

Massachusetts Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children,

United States

Pérez Byars, Natasha

Indigo Cultural Center

United States

Shivers, Eva Marie

Indigo Cultural Center

United States

Isarawong, Nucha

Barnard Center for Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health,

University of Washington School of Nursing,

United States

Walteros, Germán

Private Consulting

United States

Corresponding author: marie.celeste.condon.phd@gmail.com