Abstract

This article introduces and describes WePlay Denver, a culturally responsive, community-engaged, and evidence-informed parent-child play and support group. WePlay Denver offers groups in both English and Spanish within the local community. This article describes WePlay’s approach, how the program pivoted to launch their first virtual groups, and shares the program’s strengths, limitations, and future directions that may be applied to other early childhood and parenting support groups.

Introduction

WePlay Denver (WePlay) is a facilitated play, support, and psychoeducation program with mental health components for caregivers with young children between the ages of 6 – 36 months. WePlay was inspired by the parent-child support group of the same name at the Chicago Children’s Museum. WePlay is a caregiver-infant group model identified as a cooperative learning environment and therapeutic playgroup where participants can build their knowledge and parenting toolkit through the facilitated program content, parent-child interactions, and peer-to-peer reflections. The different dynamics and social layers between the caregiver and their child, one caregiver to another, one child to another, and the program facilitators to the participants, gives the cohort collective ownership of each session.

Using Chicago’s model of a theme-based, multi-session cohort as a launchpad, Dr. Tracy Vozar, from the University of Denver’s Graduate School of Professional Psychology (GSPP) and Sarah Brenkert, from the Children’s Museum of Denver at Marsico Campus (CMD), developed the initial WePlay Denver model. The resulting program highlights the strengths of both institutions and mental health and child development backgrounds. CMD brought the value of engagement, relationships, and development through play-based educational experiences. GSPP incorporated their expertise with mental health, caregiver-child relationships, community support, and early childhood development. The program developers’ collective purpose was to offer caregivers a space for connection and respite from the challenges of parenting. Their intention was for parents to feel motivated and equipped to better connect with and support their children, leading to enhanced outcomes for both adults and children. To achieve these goals, WePlay adopted a community-engaged, culturally responsive, and evidence-informed approach, which represent the three foundational pillars of the program.

Pillar I: WePlay is Community-Engaged

WePlay was designed by and for the community with a commitment to utilizing a flexible caregiver-driven approach, increasing the accessibility of services and building strong community partnerships. During the early stages of content development, the WePlay team scheduled a series of focus groups. By inviting community voices to the planning table, the team hoped to learn more about individual’s interests, successes, and challenges of parenting. Focus group participants were primarily recruited from MotherWise, a Denver-based community organization that connects family-centered and health-focused resources to young, low-income families in Colorado (Baumgartner & Paulsell, 2019). Through this existing partnership between MotherWise, GSPP, and CMD, WePlay team members were able to attend English-speaking and Spanish-speaking community events hosted by MotherWise and connect with prospective families. Those who expressed interest in being part of the focus group, and/or in the pilot WePlay cohort, provided their contact information. CMD hosted separate English-language and Spanish-language focus groups between March and September of 2019. During the English-language focus groups, 6 parents attended; 5 of which identified as mothers and 1 as a father, all ranging in age from their 20’s to 40’s. During the Spanish-language focus groups, 2 parents attended; both identified as mothers and members of the Latinx community, ranging in age from 20s to 30s. The team provided food, transportation, a gift for the child, free admission to CMD, and on-site supervision of children present during the focus group to enhance participation.

The scope and sequence of WePlay Denver groups were built off of the preferences and interests expressed within the focus groups and from conversations with community partner organizations. Some of the main themes to develop and directly inform the content of WePlay included helping children socialize, meeting other parents, reducing stress, understanding early childhood development, managing our own emotions, and creating opportunities to play. Participants wanted to hold WePlay groups in a community space like CMD that would help them feel comfortable and welcomed in a therapeutic playgroup. They also expressed interest in focusing the group’s educational and developmental content on younger children, ranging from early crawlers to early walkers, which resulted in the WePlay planning team selecting the 6 months to 15 months age range for the pilot group. On a case-by-case basis, children that were outside of the age range were considered for participation in the pilot cohort (e.g., two families who participated in the focus groups with children that were slightly outside of the age range were included in the pilot cohort).

The team also noticed differences in the hopes and interests between the English-language and Spanish-language focus groups, validating the team’s inclination to develop content to suit the community, cultural, and engagement needs of each cohort within the program. For example, themes of interest in the English-language group included ways to play and engage with very young children and child development. In the Spanish-language group, families were more interested in support around transitioning back to work as new parents as well as English-language support. These differences were incorporated into the initial WePlay sessions. Recruitment for focus groups, and particularly the Spanish-language group, was limited, therefore, plans were developed to ask potential participants for their input on group content during the initial recruitment discussion.

As the WePlay planning team built out the scope and sequence for the program’s pilot cohort, the intended audience was informed by the feedback gathered from the focus groups, the age range, and the developmental stage of the participating infants (i.e., 7-17 months). The program content was designed to include age-appropriate and responsive play, caregiver support, engaging materials and activities, enriching take-home materials, and continuous activities beyond the program’s sessions. The pilot’s format evolved into a 6-week series, with each 90-minute session focusing on a specific type of play and a developmentally informed psychoeducational topic, with paired take-home materials and resources to continue the learning beyond the walls of CMD. In addition, based on focus group input and support from grant funding, all participants accessed WePlay services for free, received access to transportation, snacks for both the caregiver and child during each session, and a year-long family membership to CMD. All of these factors are used as incentives for recruitment and retention to encourage weekly participation from the families. The team found that these factors, particularly the access to free transportation and free CMD admission for their family members during WePlay sessions, were successful in motivating participants’ attendance. Using the early feedback from focus groups and ongoing feedback from cohort participants, the WePlay planning team continued to prioritize factors that would help reduce logistical barriers and stressful aspects that may discourage participants from attending.

GSPP and CMD recognize the presence of implicit bias, including socio-economic bias, in the planning and facilitation of these groups is the result of operating as a small team; the knowledge, research, perspectives, and life experiences are therefore limited to those within the group. The awareness of implicit bias, paired with a strong investment in creating a continuous and cooperative learning environment for all, motivates the WePlay team to remain evidence-based and be responsive to the varying needs or interests from one cohort to the next. As a way to help minimize socio-economic bias, for example, the WePlay team offers the same incentives for all participants, regardless of their income status. In addition, WePlay is aware that the incentives participants receive may impact responses in interviews and on questionnaires, thus reflecting more positive and favorable program findings. In an effort to minimize positive responding due to incentives, all group members received incentives before completing the final surveys and feedback interviews and interviews were conducted by a team member new to the group members. While incentives may have impacted participants’ responses, WePlay team members were intentional and found success in welcoming feedback from families in an effort to improve future groups.

Flexible caregiver-driven approach. Through this pilot experience, the team saw early success with the flexible, caregiver-driven approach. Facilitators from GSPP and CMD teams are present during each group session and work to invite participants to ask questions and engage in discussion. This open dialogue format contributed to the warm and inviting nature of the program. Making the content relatable for the whole group and inviting participants to bring their own experiences into the conversation created a sense of authenticity that likely would not have been achieved otherwise. It also helped to dispel parental concerns, worries, and to normalize behaviors displayed by their child. For example, through group dialogue, parents heard from other parents and facilitators that the concerning behaviors their child was exhibiting (e.g., mild aggression towards peers or siblings, difficulties sharing) were common with the other children in the group and during their developmental period. In groups, parents and facilitators shared helpful approaches to address challenging behaviors and ways to scaffold positive behavior (e.g., quotes from participants illustrating this are included below).

As a result of the personal experiences shared by other caregivers and the informed perspectives shared by WePlay team members, many participants felt empowered to embrace new information to address unhelpful advice and criticisms from family members. For example, a parent was being criticized by family members for picking up her infant when he desired, suggesting that she was spoiling him. After discussing with the group and sharing anecdotal and research evidence that you cannot spoil a baby, the parent felt heard and supported. She asked, “Can I film you saying this for Facebook?”, and laughed.

Every week, new topics of interest and ideas generated by group members were discussed by the WePlay team and new materials were generated to be responsive to group members’ interests. In addition, facilitators queried group members regularly during groups to ask if there were additional topics or types of play that they would like covered. For example, one family was struggling with toilet training and asked that this topic be discussed during the group. In response, both group members and facilitators listened to the parent’s questions and struggles, provided useful strategies, and followed up with resources. During the next session, the parent described the group’s assistance and attention to the toilet training topic to be very helpful, both in terms of the child’s progress and parent-child relationship.

The WePlay team strongly believes that this flexible, caregiver-driven approach, resulted in steady attendance and retention. This overall format felt strong and responsive towards the caregivers in the initial groups, so the team felt encouraged to carry the collaborative approach forward into subsequent cohorts.

Accessibility. WePlay also emphasized accessibility. All participants were offered either free rides to and from CMD or free parking. In addition, because some participating families also had older children, CMD offered free admission to siblings and other family members during and after WePlay sessions to minimize the need for additional childcare.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, WePlay moved its programming online. The team created a website that provided access to online resources, including videos demonstrating play activities and discussing psychoeducational topics. The website also included information about accessing mental health care during the pandemic, tips on how to talk about the virus with young children, and links to other online activities for families, such as live music time and virtual dance parties. The team also reached out to WePlay families that had either been a part of the recruitment contact list or past participants. The respondents generously offered their insight related to learning topics, the value of play, what sort of resources they needed, which digital platforms they preferred, and more. This information helped the team to validate, reshape, or create ideas for this new era of WePlay including topics that were specific to the events of 2020, such as COVID-19, discussing racial justice with children, and mindfulness.

In fall 2020, WePlay held its first virtual groups. Prior to sessions, the team delivered the physical materials used in the WePlay program to the participants’ homes for use during the online sessions. The kits featured open-ended toys and objects that support multiple levels of developmentally-appropriate play, such as juggling scarves, egg shakers, plastic cups and bowls, sensory balls, and more. Kits also included bilingual board books, printed infographics, snacks, gift cards for groceries or home goods, and a free family membership to CMD. The intended goal of providing these interactives was to share different ways to activate play-based learning using multi-functional items or everyday objects, ultimately giving families autonomy in deciding how they want to use these materials. One family, for example, used the hand-made sponge balls and measuring cups from one session to make their bath times more playful. Another child used a plastic storage bin as a multipurpose bathtub and bed for her dolls. The use of everyday objects in these kits also helped to foster the creativity and reimagining of other everyday objects within families’ living space. For example, if cups and bowls were included in the kit, it would be an opportunity to talk about channeling imaginative and creative play by using these objects as drums as well as encourage families to identify other household objects that could also be used as a musical instrument. This approach to play-based learning encourages positive development and interactions through simple and easy-to-replicate ideas diminishing barriers in accessing resources.

Virtual sessions were reduced to 60-minute experiences based on previous group members and facilitator feedback of how much time was feasible and enjoyable over Zoom with young children present. Separate virtual groups were held in both English and Spanish. In order to keep WePlay as accessible as possible, team members worked with families to troubleshoot any connectivity or technical issues before and at the start of sessions. Because this first-ever approach to virtual WePlay included primarily returning participants, the children in the initial virtual groups were between the ages of 6-32 months.

Community partnerships. The WePlay program is also committed to fostering community partnerships. For example, one of WePlay’s main referral sources is MotherWise Colorado, a local organization that provides free parenting workshops to empower women and families (Baumgartner & Paulsell, 2019). In addition to the central collaboration between GSPP and CMD, WePlay partners with the Denver Botanic Gardens to provide families with access to unique child-friendly activities. In addition, WePlay partners with Rocky Mountain Human Services (RMHS), an agency that provides various supportive services for families and children including early intervention. Through the partnership with RMHS, families with children who have special needs have participated in WePlay. WePlay conducted its first virtual cohort with families recruited from RMHS and look forward to incorporating feedback received into future groups so that WePlay can continue to provide tailored and supportive services to families with special needs and developmental considerations. Finally, the WePlay program is committed to expanding access to mental healthcare for families with young children. WePlay provides an important port of entry for parents adapting to the stressors of parenting. The WePlay program has connected many participants with free or low-cost services from area clinicians that specialize in perinatal to five years, mental health6.

Pillar II: WePlay is Culturally Responsive

A key foundation of the WePlay model is the importance of culture and language in the developing caregiver-child relationship. The cultural sensitivity of the WePlay model is particularly pertinent because it addresses the needs present within the population of Colorado. Approximately 12% of Colorado’s population speaks Spanish (Colorado Health Institute, 2015) and 1.1 million Coloradoans identify as Latinx (Latino Leadership Institute, 2017). Both nationally, and in Denver, very few mental health professionals are able to offer services in Spanish, which contributes to poor communication between Hispanic individuals and their health care providers (American Psychiatric Association, 2017). WePlay-Español facilitators and supervisors are culturally and linguistically sensitive clinicians trained in offering evidenced-based psychotherapy in Spanish and English. WePlay-Español accounts for different culture-specific core values (e.g.: simpatia and respecto) and stressors such as social mobility, adaptation problems to a new language, behavioral norms, and values of the new environment (Rogler et al.,1991, cited in Welsh, 2013). WePlay-Español facilitators aim to reduce acculturative stress from assimilation issues (Crockett et al., 2007), thus promoting mental well-being (American Psychiatric Association, 2017) while supporting participants around childcare practices and normative developmental behaviors. By providing information, clarifying doubts, and answering questions, WePlay-Español helps to fill a gap for participants who may feel hesitant or unwilling to ask questions of their care providers for fear of appearing disrespectful.

WePlay values cultural responsiveness in several ways, perhaps most specifically by offering separate groups in two of the dominant languages in our community, English and Spanish, and by creating content based on the interests of each cohort. The cultural sensitivity addressed by this model is not limited to language. WePlay addresses the specific needs and interests of each group. As mentioned previously, the focus groups indicated notable differences in the needs and interests of the English and Spanish participants, which lead to different content in the subsequent groups. For example, in the English group, parents were more interested in learning about parenting skills, whereas in the Spanish group there was a higher interest in learning about how to keep the culture of origin while adapting to a new culture. In addition, the Spanish language group was more likely than the English language group to share their personal experiences, which often shifted focus in the Spanish language group to topics such as challenges in accessing medical care. WePlay-Español facilitators follow the lead of the participants when a new topic would arise and would share resources, if available. WePlay Español facilitators also take note of new topics to bring up as possibilities for discussion in future cohorts.

In addition to understanding differences across the English and Spanish-speaking groups, it is important to highlight and consider the intra-group differences in WePlay-Español. For example, participants differed in how long they have been in the United States and their degree of acculturation and assimilation with American culture varied. Participants’ also differed in their willingness to share lived experiences and details about their multifaceted cultures. Furthermore, although all members within a cohort spoke the same language, participants often spoke different dialects reflective of different countries or regions. Participants’ range of abilities in speaking and understanding English was also reflective of these intra-group differences. A similar challenge expressed across WePlay-Español participants was how to adapt to American culture and parenting practices while also preserving their own culture and heritage. These shared experiences facilitated enriching discussions, regarding topics such as bilingualism and how to honor participants’ ancestral cultures, and permeated the conversations in WePlay Español.

Pillar III: WePlay is Evidence-Informed

The WePlay program aims to support caregivers and their young children by sharing best practices from nationally recognized early childhood organizations (e.g., Zero to Three; Harvard University’s Center on the Developing Child), as well as incorporating findings from empirical research regarding temperament and differential susceptibility, addressing challenging behaviors, and strengthening attunement (e.g., Belsky et al., 2007; Troutman et al., 2012; Troutman, 2015; Troutman, 2016; Marvin et al., 2002) into the program’s psychoeducation and resource materials. WePlay understands that in order to promote healthy child development, it is imperative to support caregivers’ well-being and mental health (Mensah & Kiernan, 2010; Smith, 2004). Therefore, WePlay invites discussion of caregiver-focused topics such as social support and self-care practices. In addition, caregivers are introduced to empirically supported parenting strategies, such as skills and techniques from Integration of Working Models of Attachment – Parent Child Interaction Therapy (IoWA-PCIT; Troutman, 2011) as well as parenting resources from Zero to Three and other credible sources, that promote children’s positive social and emotional development.

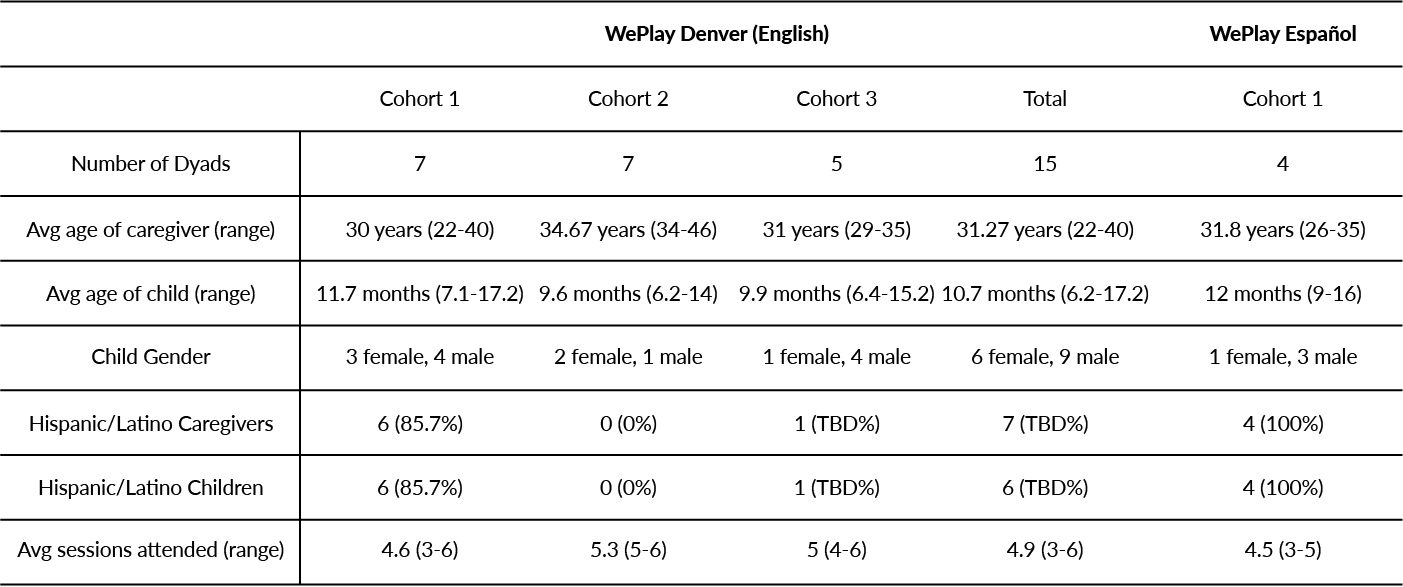

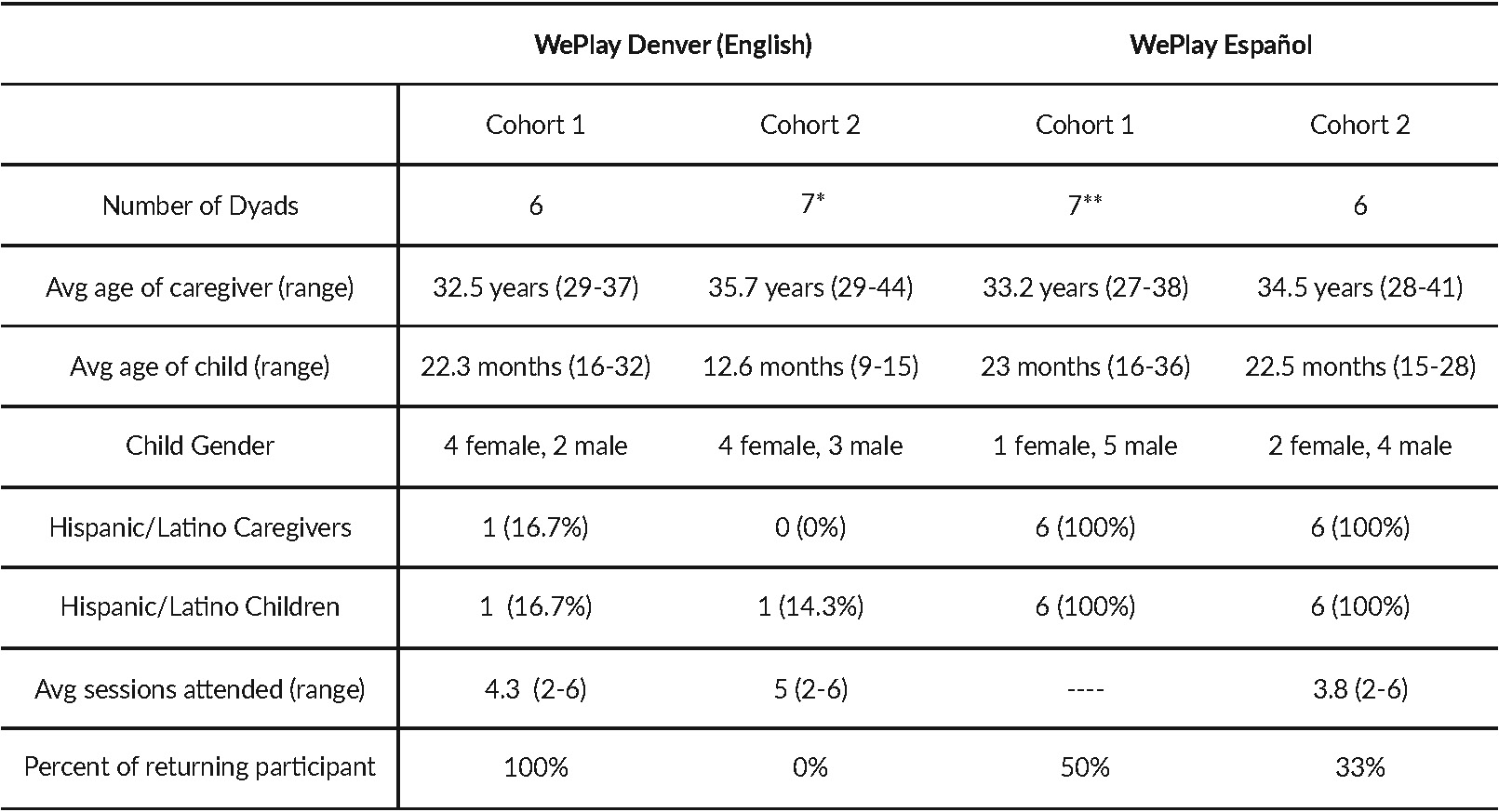

WePlay also applies findings from program evaluation research into the development and planning of groups. WePlay collects pre- and post-group data on several important indicators associated with positive outcomes for caregivers and children, including caregiver well-being, mental health, and parenting-related factors. More specifically, caregivers’ depression and anxiety symptoms are assessed using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression (Cox et al., 1987) and the Postpartum Worry Scales (Moran et al., 2014). In addition, caregivers’ parenting self-efficacy, parenting stress, and self-compassion as assessed using the Assessment of Parenting Tool (Moran et al., 2016), the Parenting Stress Index-Short Form (Abidin, 1995), and the Self-Compassion Scale-Short Form (Raes et al., 2011). Data collected for each English and Spanish cohort helps WePlay facilitators better understand how participation benefits caregivers and children as well as which areas WePlay may need to target with additional support. Demographic data of WePlay English and Español cohorts are included in Tables 1-2. Descriptive data from WePlay’s pre-and post- group surveys will be analyzed in future dissemination efforts. In addition to reporting scales, caregivers are invited to participate in a brief 20- to 30-minute semi-structured post-group interview regarding their experiences in WePlay. Results from each cohort are reviewed by the team and integrated into the planning of future WePlay groups.

Table 1. Demographic Data from in-person WePlay Groups.

Table 2. Demographic Data from Virtual WePlay Groups.

Note. * One family had twin children, so there were 6 caregivers and 7 children

** Missing data from 1 participant. Only 6 dyads used for subsequent calculations.

Attendance data was not collected from WePlay Español Cohort 1.

Qualitative data for all English language cohorts, in-person and virtually, were examined using a thematic analysis approach and analysis of data for Spanish language cohorts is planned for the coming year. Themes across interviews from in-person WePlay English groups (total n= 15 caregiver-child dyads, across 3 cohorts) highlighted how the psychoeducation components of the group helped caregivers learn about parenting approaches, child development, and how to best meet their child’s needs. Caregivers expressed how beneficial it was to learn from other caregivers with children of similar ages and how validating it was to share similar experiences with peers. Caregivers appreciated the focus on caregiver well-being in groups and learned how important it is to care for themselves as well as their children. Children enjoyed the groups and caregivers appreciated how groups offered opportunities for children to socialize with peers around their developmental stage. Children and caregivers also enjoyed WePlay materials and activities and continued to engage with them after the program concluded. Overall, the positive experiences during WePlay were evidenced by the number of caregivers requesting program extension and interest in re-joining future groups.

“Yes – especially old age stuff about you spoiling them or they are trying to manipulate. And I learned that you really can’t do that. Reassuring that you are there and paying attention to their needs instead of closing up.”

Caregiver from WePlay English In-Person Group (When asked if they learned things from the group)

“I did. I learned that some of the challenging behaviors were typical for his age. It was helpful to know that it was not specific to him but just part of development. It wasn’t that I was doing something wrong. And I learned some tips on how to manage his behavior as well as how I react to those challenging moments.”

Caregiver from WePlay English In-Person Group (When asked if they learned things from the group)

Preliminary qualitative data (n = 6 caregiver-child dyads, all returning participants) from the English language WePlay virtual groups with children between 6-32 months of age suggested caregivers’ appreciated weekly material deliveries, play activities, timely psychoeducation topics (e.g., toilet training, wearing face masks during the pandemic, dealing with tantrums, and raising anti-racist children), and hearing fellow caregivers’ perspectives on psychoeducation topics. Data also suggested that weekly reminders including Zoom information facilitated group attendance. In addition, while caregivers noted how great it was for their children to see other kids, it was sometimes challenging to engage children through virtual formats, as would be expected developmentally. Lastly, caregivers noted several recommendations to increase child engagement, provide additional opportunities for caregivers to request psychoeducation topics and expressed wishes to expand and grow WePlay to include more families and varying developmental ages.

“…I think there was room to ask about whatever was going on in your life so I appreciated that. For me, those were two things that were coming up and I talked to Tracy about them or other people in the group and they were really helpful with ideas so I like the ability to talk about whatever was going on in our life. I like the ability to bring up questions and talk about life…”

Caregiver from WePlay English Virtual Group

Furthermore, qualitative data from our virtual WePlay cohort (n = 6 caregiver-child dyads) recruited through RMHS with children between 9-15 months of age suggested families appreciated the accessibility of virtual group formats, psychoeducation topics and play activities, receiving validation for parenting struggles, learning from other parents’ experiences, having a space to connect with other families, as well as children seeing other children. Some families provided feedback that the timing of the group conflicted with their child’s nap schedule. They also suggested that future groups could include examples as to how enriching activities may be incorporated into everyday activities. Furthermore, families expressed wanting more interactions with other parents but also acknowledged the inherent limitations of the virtual format. Lastly, families shared new play material ideas (e.g., household objects such as couch cushions).

Challenges

While WePlay’s flexible and caregiver-led approach promotes tailoring of support and resources to directly meet the needs of the community, this non-manualized model is accompanied by several challenges regarding implementation fidelity, program evaluation, and grant funding.

WePlay does not use a manualized approach but rather integrates various theoretical perspectives to inform and guide the team’s approach to groups. For example, psychoeducation topics and activities designed to strengthen caregiver-child attunement are conceptualized through an attachment theory perspective (Ainsworth, 1978), while content aimed to address disruptive and challenging behaviors derives from integrated behavioral and attachment frameworks (Troutman, 2015; Troutman, 2016). The importance of considering caregivers’ and children’s individual differences and goodness of fit inform our discussions on creating an environment that is responsive and sensitive to the temperamental and relational characteristics of participants (Chess & Thomas, 1991).

Using a non-manualized approach introduces challenges in implementing groups with fidelity. Because cohort groups are each unique and topics are informed by the members of each cohort, it is difficult to communicate the exact learning objectives of each group cohort session until WePlay is underway. WePlay’s non-manualized approach also presents complications in program evaluation. Because caregivers in different cohorts are potentially being introduced to different psychoeducation topics and play activities, it is hard to determine which aspects of the groups are leading to various outcomes. Instead of identifying which specific topics and activities facilitate change, WePlay is curious to evaluate the holistic effectiveness of flexible caregiver-led groups in caregiver and caregiver-child relationship outcomes.

Lastly, because the majority of program funders and stakeholders favor a manualized approach that is strongly supported by empirical research, it is difficult to ensure WePlay’s financial sustainability. Without funding, WePlay is unsupported in regard to dissemination, sustainability of services in current communities served, and in expansion efforts of services outside of the Denver metro area. The team plans to utilize innovative programmatic evaluation techniques that showcase the value of flexible caregiver-led programs and promote funders’ interest and engagement.

Strengths

A unique strength of the WePlay program is the collaboration across museum and academic staff. CMD team members bring knowledge of child development, play, and activities that are novel in academic mental health programming. Similarly, clinical psychology faculty, staff, and trainees bring expertise in social-emotional development, perinatal to five mental health, Latinx psychology, and parent-child relationship development that is novel to the CMD setting. The team as well as group members have found this unique collaboration to be an excellent fit for the specific goals of the WePlay program and participating families. The team members learn from one another, and the group members learn with a dynamic interdisciplinary group of facilitators. The content, breadth, and depth within the group has expanded as a result of the skills and knowledge each team member brings to WePlay. Further, for group members who might hesitate to join a group within a formal clinical setting, the museum setting, focus on play, and relationship-based curriculum are welcoming characteristics. On numerous occasions, the WePlay program has been the initial port of entry for engaging families in additional mental health services. Our team has also benefited from a train-the-trainer model wherein staff, students, and faculty who have led a prior group are shadowed by newer team members. In this way, new team members learn the WePlay model by actively participating in the groups, with the support of more experienced members. This training strategy facilitates program replication and expansion.

Given the newness of the WePlay approach and the various team members and knowledge areas combined in the model, the team put in place various feedback mechanisms among stakeholders. First, one of the team members shadowing a more experienced staff person would take notes during the group to be shared at the next team meeting. Team meetings occurred following group sessions and provided a space for reflection, shared observations, noted strengths and challenges of the group, and potential areas for revision in future groups. The ever-evolving nature of the group’s content meant an openness to new topics and activities. The adaptability to new content also meant that team members often had to think quickly and creatively during a session or plan to address a topic the following week after generating new content. Sometimes planned activities or topics were swapped for other, more pertinent topics such as when the topic of promoting sleep practices was not a pressing concern for the group but supporting and troubleshooting toilet training was.

Another unique strength of the WePlay program is the training opportunities it provides for students. Clinical psychology doctoral students were involved in all aspects of the approach from the initial planning, focus groups, and design of the broader WePlay curriculum. In addition, WePlay allows students to provide group support to parent-child dyads in a less clinical setting, providing students with a unique clinical experience. Similarly, WePlay provides students with the opportunity to be involved in an ongoing and malleable community-focused research project, where students connect with community partners, help collect and analyze data, and use participant feedback to modify the content and structure of future WePlay groups.

WePlay’s model of incorporated mental health screening and referrals offers trainees the experience of providing both group psychoeducation and more intensive clinical services when needed. Due to the unique, community-based, and collaborative nature of WePlay, many trainees are excited to volunteer to participate. WePlay benefits from the trainees’ excitement by having plenty of staff to facilitate groups and to co-create content. In addition, students (including three of the current authors) have been actively involved in associated presentations and publications describing the WePlay program, thereby promoting their overall professional development.

Previous research on parent-child playgroups has demonstrated positive effects in numerous areas. Studies have found that these types of groups not only provide parents with valuable information about parenting, they also allow participants to make friends, build a peer support network, and foster a sense of community (Strange et al., 2014). Another study found that improvements in parent-child interactions were maintained up to 32-weeks after participating in a parent-child playgroup, suggesting that the positive impacts of groups are long-lasting (Westrupp et al., 2018). While quantitative data has not been analyzed, qualitative and anecdotal data suggests that WePlay participants enjoyed peer support, information from experts on child development, and learning new ways to connect with their children. Participants also reported that the WePlay program was particularly beneficial during experiences of isolation due to the COVID-19 Pandemic.

“…(Child’s name) was born, I mean all of the babies are in the same age range, he was born last July. He’s almost one so he was born into a pandemic world so I pictured the start, I pictured especially, I don’t know, I think one of the best things you can do for the little ones is just put them together and let them learn from each other. I think that’s one of the best things you can do for new moms as well. I pictured that being part of our daily life – going to libraries or even friend’s houses or parks and that just couldn’t do it or I didn’t feel particularly comfortable until recently. So, I think that’s just what I enjoyed most even though (child) couldn’t be with the other babies playing with them directly. I can always tell that he was hearing others’ voices which is so nurturing for him. He was able to play with so many new materials. Yeah, so it really just provided the space that was good for the babies and I think good for the moms too. So I really look forward to just that time of being together. And I think everyone would have preferred to be in person. I know that we would have. But it was filling this gap that we have been missing in this first-year. “

Caregiver from WePlay English Virtual Group

“I just wanted to say thank you. The groups were really amazing, and we were so, so honored to be a part of them. We get to learn so much and we get to, you know do something. It was so exciting like ‘yay, every Tuesday we have this!’”

Caregiver from WePlay English Virtual Group

Future Directions

As WePlay grows and expands, the team plans to collaborate with Denver metro area libraries as well as other child service agencies, such as RMHS, to continue increasing access to the WePlay program. WePlay has also begun conversations about developing a mobile shuttle that will improve accessibility for WePlay and additional mental health programming to more remote areas of Colorado. In addition, WePlay will introduce a new approach to ensure all caregivers have the opportunity to share their interests and concerns that inform psychoeducation topics. WePlay will provide anonymous pre-group surveys so that caregivers can list topics for the psychoeducation component of the group and share any details they find important about their child and/or family.

Over time, the team has found that caregivers value the perspectives of their peers and that caregivers within cohorts typically share similar psychoeducation topic ideas. Therefore, despite similarities and differences in topics covered across cohorts, WePlay plans to create a “tool-kit” of psychoeducation topic resources that can increase fidelity regarding the content covered. The tool-kit will also be beneficial to others who wish to replicate or offer similar programs in their communities. Furthermore, WePlay will continue to tailor and develop content and materials for cohorts with children across varying developmental stages and who have special developmental needs and considerations. Consistent with WePlay’s program model, feedback from the program participants, community partners, and other WePlay stakeholders will be continually solicited and integrated into future program planning and development.

References

Abidin, R. R. (1995). Parenting Stress Index, Third Edition: Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, inc.

Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Hillsdale, N.J. : New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

American Psychiatric Association. (2017). Mental Health Disparities: Hispanics and Latinos. https://www.psychiatry.org/File%20Library/Psychiatrists/Cultural-Competency/Mental-Health-Disparities/Mental-Health-Facts-for-Hispanic-Latino.pdf

Baumgartner, S., & Paulsell, D. (2019). MotherWise: Implementation of a Healthy Marriage and Relationship Education Program for Pregnant and New Mothers, OPRE Report # 2019-42, Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and human Services.

Belsky, J., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & van Ijzendoorn, M. H. (2007). For better or for worse: Differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Current Directions in Psychological Science: A Journal of the American Psychological Society, 16(6), 300-304. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00525.x

Chess, S., & Thomas, A. (1991). Temperament and the concept of goodness of fit. In J. Strelau & A. Angleitner (Eds.), Explorations in temperament: International perspectives on theory and measurement (pp. 15-28). Plenum Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-0643-4_2

Colorado Health Institute (2015). Speaking of Health: A Look at the Health of Colorado’s Spanish Speakers. Colorado Health Access Survey. Retrieved from www.coloradohealthinstitute.org

Cox, J. L., Holden, J. M., & Sagovsky, R. (1987). Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 150, 782-786. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.150.6.782

Latino Leadership Institute. (n.d.). Latino Colorado. Retrieved from https://latinoslead.org/latino-research/

Marvin, R., Cooper, G., Hoffman, K., & Powell, B. (2002). The Circle of Security project: Attachment-based intervention with caregiver-pre-school child dyads. Attachment & Human Development, 4(1), 107-124. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730252982491

Mensah, F. K., & Kiernan, K. E. (2010). Parents’ mental health and children’s cognitive and social development: families in England in the Millennium Cohort Study. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology, 45(11), 1023–1035. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-009-0137-y

Moran, T. E., Polanin, J. R., & Wenzel, A. (2014). The Postpartum Worry Scale-Revised: An initial validation of a measure of postpartum worry. Archives of Women’s Mental Healh, 17(1), 41-48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-013-0380-9

Moran, T. E., Polanin, J. R., Evenson, A. L., Troutman, B. R., & Franklin, C. L. (2016). Initial validation of the Assessment of Parenting Tool: A task- and domain-level measure of parenting self-effiacy for parents of infants from birth to 24 months of age. Infant Mental Health Journal, 37(3), 222-234. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21567

Pew Research Center tabulations of the 2017 American Community Survey (1% IPUMS). https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/09/16/key-facts-about-u-s-hispanics/

Raes, F., Pommier, E., Neff, K. D., & Van Gucht, D. (2011). Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the Self-Compassion Scale. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 18(3), 250-255. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.702

Rogler, L. H., Cortes, D. E., & Malgady, R. G. (1991). Acculturation and mental health status among Hispanics: Convergence and new directions for research. American Psychologist, 46(6), 585–597. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.46.6.585

Smith M. (2004). Parental mental health: Disruptions to parenting and outcomes for children. Child & Family Social Work, 9(1), 3-11.

Strange, C., Fisher, C., Howat, P., & Wood, L. (2014). Fostering supportive community connections through mothers’ groups and playgroups. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70(12), 2835-2846.

Troutman, B., Moran, T., Pelzel, K., Luze, G., & Lindgren, S. (2011). Developing a blueprint for training Iowa providers in early childhood mental health. Iowa Early Childhood Mental Health Professional Development Work Group.

Troutman, B. (2015). Integrating Behaviorism and Attachment Theory in Parent Coaching (1st Ed.). Springer International Publishing https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-15239-4

Troutman, B. (2016). Integrating behaviorism and attachment theory in addressing disruptive behavior. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 55(10), S229. doi:10.1016/j/jaac.2016.09.396

Troutman, B., Moran, T. E., Arndt, S., Johnson, R. F., & Chmieliwski, M. (2012). Development of parenting self-efficacy in mothers of infants with high negative emotionality. Infant Mental Health Journal, 33(1), 45-54. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.20332

Westrupp, E. M., Bennett, C., Cullinane, M., Hackworth, N. J., Berthelsen, D., Reilly, S., Mensah, F. K., Gold, L., Bennetts, S. K., Levickis, P., & Nicholson, J. M. (2018). EHLS at School: school-age follow-up of the Early Home Learning Study cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC pediatrics, 18(1), 148. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-018-1122-y

US Census Bureau. (2015). Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014-2060. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.pdf

Authors

Gross, Lauren, M.A.*

Lavin, Kelly, Ph.D.*

Moormeier, Kayce

Pahwa, Esha, M.A.

Cerqueira, Mariana, M.D., Mpsy

Moran Vozar, Tracy, Ph.D., IMH-E® (IV-R/F)

(*equal contributions)