ZERO TO THREE Corner

The international adoption of children who have been raised in institutions abroad is on the rise in the United States and is not without controversy. Reasons for the increase include higher rates of infertility in couples who have delayed parenthood; increased numbers of children who are relinquished, abandoned, or orphaned around the world; and the influence of third party agencies. Internationally adopted children face numerous risks and vulnerabilities, including the loss of their family, country, language, and culture. Critics argue that international adoption helps a relatively small number of children who find adoptive parents but may impede countries from developing social programs that would benefit the vast majority of children who are suffering due to poverty or social and political problems.

The issue of international adoption has featured prominently in media headlines, spurred in recent years by public interest in the family-building activities of superstars such as Angelia Jolie and Madonna. Although newsworthy and fashionably interesting, neither the practice nor the controversy surrounding international adoption is new. As Rosenblum and Olshansky (2007) highlight in their discussion of diverse pathways to parenthood, adoption plays a significant role in the formation of kinships in the United States, with roughly 2.5% (16 million) of all children under age 18 being adopted (U.S. Census Bureau, 2007). Likewise, international adoptions have increased from 5% of all adoptions in the late 1980s to 15% of all adoptions in 2001 (Kane, 1993; Selman, 2002), a threefold increase that indicates significant growth in the popularity of adoption as a method of family building (Johnson, 2005).

International adoption is currently estimated to involve over 40,000 children a year moving between more than 100 countries (Juffer & van IJzendoorn, 2005). The 2000 U.S. census reported 199,136 international adoptees younger than 18 years living with families in the United States (Johnson, 2005) and official U.S. immigration data indicates a further increase of 107,841 over the four years 2001–2005 (U.S. Department of State, 2007a; U.S. Department of State, 2007b). Given the scale of the increase, there can be little doubt that hundreds of thousands of American families, their child-care practitioners, and other service providers are participating in and are directly or indirectly affected by the explosive growth in international adoption.

Trends in international adoption in the United States

The early history of international adoption has been well documented (Altstein & Simon, 1991; Selman, 2002; Weil, 1984). It emerged as a valued, legal, and morally motivated practice in the aftermath of World War II, when thousands of orphaned and destitute European children were brought to the United States. International adoption in this earlier period was motivated by care and concern for children in distress in foreign countries.

In the latter part of the 20th century, American involvement in conflicts in Korea and Vietnam increased the motivation for and practice of international adoption. Other factors included the humanitarian fallout from civil conflicts in countries such as Greece, El Salvador, and Haiti, and, more recently, the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe and the introduction of population control initiatives in China (Hollingsworth, 2003; O’Halloran, 2006).

Trends and patterns in international adoption over time suggest that increases in international adoption are not generally motivated by humanitarian responses to war and conflict (Selman, 2002). Instead, they have become an attractive option for infertile couples in western societies, who may or may not also be motivated by the desire to care for children in need. Whereas in the 1960s and 1970s adopters might have been motivated to assist children in need of a home, potential adoptive families today are seeking babies who are healthy and voluntarily relinquished (Momaya, 1999; O’Halloran, 2006).

During the last three decades, several studies (Kane, 1993; Selman, 2002; Weil, 1984) have examined the growth and trends in the migration patterns of children through international adoption, both worldwide and to the United States. These studies have demonstrated a rapid and significant increase in the number of international adoptions to the United States since the 1980s. In comparison to other countries, the United States has shown the biggest growth in international adoptions and now accounts for over half of all such adoptions worldwide.

Most analysts agree (Hollingsworth, 2003; Johnson, 2005; Kane, 1993; Selman, 2002; Weil, 1984) that three important factors have driven the increase in international adoptions to the United States:

- Increased demand for children from within the United States.

- The abject poverty of southern hemisphere countries and the subsequent abundant number of children who have been abandoned, left destitute, or relinquished by their birth families, in addition to those who have been orphaned.

- The activities of third parties, such as adoption agencies, who strongly influence and facilitate the current child migration process.

In addition, the following factors have played a specific role in the increasing demand for international adoption in the United States.

Increased reproductive health choices and decreased fertility

Most western societies have seen a drop in fertility rates over the last few decades, and the United States is no exception. Current reproductive trends indicate that at least one quarter of American women have their first baby after 35 years of age. This, along with greater reproductive choices, has led to increased involuntary infertility. The net result has been that fewer unplanned or unwanted infants are born in the U.S., and many more parents find themselves unable to build a biological family later in their lives (Darnell, 2004; Johnson, 2005; O’Halloran, 2006; Selman, 2002).

Increased maternal choice and support for unmarried mothers

Increased maternal choices to retain rather than relinquish a nonmarital child have played a significant role in reducing the number of children available for domestic adoption. Declining stigma, coupled with welfare benefits and support services, has allowed single parenting to become a feasible option, and has resulted in fewer American children being made eligible for domestic adoption (Hollingsworth, 2003; Johnson, 2005; O’Halloran, 2006).

Birth parents’ rights and open adoption systems

Increased protection of birth parents’ rights, the development of the foster care system, and the movement away from closed adoptions have influenced the number, age, and nature of children available within domestic adoption systems. Currently, a child’s eligibility for adoption is determined more by court processes than by parental choice. Children being made available for adoption tend to be older, with some level of mandated contact with birth parents (Johnson, 2005). Despite the changing demographic in nationally available children (e.g., in 2001 only 2% of children adopted from foster care were less than 12 months, as compared to 44% of international adoptees that year), the demand for younger children and closed adoption has remained constant (Johnson, 2005; O’Halloran, 2006)

Commercially driven adoption agencies and third party placements

The United States (unlike the United Kingdom) permits independent and third-party adoption placements; consequently, commercially driven agencies are frequently involved in facilitating adoption placements from overseas countries (O’Halloran, 2006). Evidence suggests that international adopters in the United States are economically advantaged, educated, and older (Juffer & van IJzendoorn, 2005; Momaya, 1999; Wallace, 2003). Waiting periods for national adoption tend to be longer regardless of wealth and somewhat less certain, based on age or marital status. In the international adoption arena wealth, or buying power, is often able to facilitate adoption placements. Adoptive parents may have greater choice in the age and background of the child and a shorter waiting period, if they are willing to spend significantly more money than they would for a national adoption. Factors that may influence eligibility in the United States are often much less restrictive in the international adoption arena and more influenced by other eligibility criteria, such as income and willingness to adopt (O’Halloran, 2006).

Risks and controversies

Along with the increasing demand for and rapid growth in international adoption, growing concerns have been raised by or on of behalf of sending countries. These concerns have mainly centred on the following issues.

The removal of adoptable children from their birth country

International adoption, in particular recent trends demonstrating an increase in the demand for younger, healthy infants, may lead to the removal of the most adoptable children from their own countries (O’Halloran, 2006). International adoption preempts the possibility of meeting the needs of native adopters and leaves behind children who are statistically less likely to be adopted. Several analysts (Hollingsworth, 2003; Selman, 2002; Wallace, 2003) have raised concern over issues of social justice and inequity in the current era of explosive growth.

The removal of children from their birth culture and kin

International adoption often results in a permanent removal of a child, either directly, through a closed adoption process still allowed in many sending countries although prohibited in the United States. or indirectly, by the financial and geographic barriers to continued contact with birth culture and kin (O’Halloran, 2006). This may have implications for the future development and identity rights of the internationally adopted child (Mohanty & Newhill, 2005). Despite the fact that international standards encourage adoptive parents to ensure the child has an opportunity to learn about their birth culture, evidence shows that very few adopting families are able to sustain this over time (Wallace, 2003)

Circumstances of poverty often create greater vulnerability

The unremitting poverty and hardship experienced in poorer sending countries often make birth parents more vulnerable to pressure to relinquish a child for financial gain (O’Halloran, 2006). A lack of support services and poverty increase the likelihood of abandonment of children, in particular if birth parents feel they are giving the child a chance at better care (Hollingsworth, 2003; Wallace, 2003). Furthermore, postadoption opportunities for contact are limited, either by the nature of the adoption, or by the inability to practice openness because of the distance and financial resources required. Consequently, access to “open” adoptions is severely limited (O’Halloran, 2006).

Market-driven economies introduce new risks for children

The current rapid growth in the movement of children across borders and the increased demand and supply of children has resulted in market-related conditions developing for the legitimate trade of children (Kane, 1993). However, such developments create precisely the conditions under which it becomes difficult to protect the rights of children and the “best interest of the child” are less and less likely to be taken into consideration (O’Halloran, 2006). Market-related conditions for adoptions raise concerns that the legality of an adoption process may be compromised on account of the wealth or financial status of the adopter or of their representing agency, as was demonstrated by the recent adoption by Madonna from Malawi. Although the Hague Convention on Intercountry Adoption (see box) provides an international regulatory framework, its capacity to standardise and raise levels of practice is limited by the fact that a number of countries that participate in international adoption and send children to the United States are not yet signatories, have not yet ratified the convention (Kane, 1993; O’Halloran, 2006), or do not have the capacity to implement its provisions.

The risks of increased baby trafficking

International adoption regulations within the US are stringent, but very little can be done to ensure that sending countries adhere to those regulations, regardless of whether they are signatories to the Hague Convention (D’Amato, 1998; O’Halloran, 2006)—as evidenced in the cases of Romania in the early 1990s, Cambodia in the late 1990s, and current growing concern over the adoption trade in Guatemala (Bainham, 2003; Wittner, 2003). The problems remain the same. Only the countries of focus change; as one gateway closes, another opens. Although proponents of international adoption argue that child trafficking is an unlikely and frequently exaggerated outcome (Johnson, 2005), recent history seems to suggest otherwise (Bainham, 2003; Fieweger, 1991; Wallace, 2003; Wittner, 2003). A case in point is how unscrupulous baby brokers took advantage of loopholes in Romanian law after the fall of the Soviet Union (brought to the attention of the general public in an expose by the U.S. television show “60 Minutes”), facilitating over 10,000 Romanian adoptions in 1990–1991 and resulting in an emergency moratorium on adoptions from that country (Bainham, 2003). Likewise, the exposure of baby-selling rings in Cambodia by the U.S. television program “20/20” and the resultant moratorium on adoptions from that country by the U.S. in 2001 (Wittner, 2003). These examples provide ample food for thought about the threat that international adoptions can be used for trafficking. It is naive to presume such actively does not present serious risks for children and vulnerable communities in sending countries.

meet the standards of the Convention.

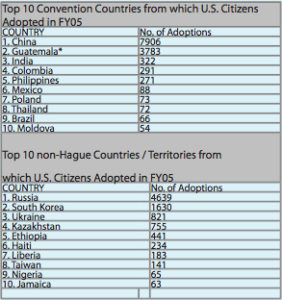

Source: U.S. Department of State

The Hague Convention on intercountry adoption

The Hague Convention strengthens protections for adopted children by:

- Ensuring that intercountry adoptions take place in the best interests of children; and

- Preventing the abduction, exploitation, sale, or trafficking of children.

Currently, 68 countries have joined the Convention, which was completed and circulated for comments by member countries on May 29, 1993, under the auspices of the Hague Conference on Private International Law, an international organization formed in 1893. The Convention is expected to be fully implemented in the United States in 2007. At that time, private adoption service providers will need to be accredited, temporarily accredited, or approved, or be supervised by a provider that is accredited, temporarily accredited, or approved, in order to provide adoption services in cases involving the United States and another Convention country.

The challenges facing international adoptees

There are many difficulties in achieving a match between the adoptive home circumstances and the needs of the internationally adopted child (O’Halloran, 2006), often because of the high degree of uncertainty within the adoption process itself, the great geographic distances over which the process has to be managed—often with considerable costs attached (Bledsoe & Johnston, 2004; Johnson, 2005)—and the difficulties in accessing verifiable information regarding parental consents, health, and genetic background (Miller, 2005b). Internationally adopted children have often come from deprived settings and from cultures in which they have multiple caregivers, and they need to make tremendous and rapid adjustments upon arrival in the United States (Mohanty & Newhill, 2005; Shapiro, Shapiro, & Paret, 2001). Some commonly cited challenges include the following.

The initial transition and adjustment to a new environment

Internationally adopted children and their new families face multiple challenges in their adjustment to family life in the United States. Many children adjust well, but understandably some find this sudden transition difficult and often display behavioral and emotional difficulties related to everyday activities such as sleeping, eating, or bathing (Miller, 2005a). The length of prior institutionalisation, if any, as well as the age of the child at adoption, can affect the ease with which children adjust to their new environment; younger children tend to adjust more quickly than older children (Diamond et al., 2003; Gold, 1996; Goldberg & Marcovitch, 1997). However, any young child who experiences a complete change in environment and routine may as a result become withdrawn or distraught. Although new parents are excited, they may be ill prepared to deal with this transitional period and require additional support (Groza & Ryan, 2002; Groza, Ryan, & Cash, 2003; Haradon, 2001; Levy-Shiff, Zoran, & Shulman, 1997; Mohanty & Newhill., 2005).

Medical, developmental, and behavioral challenges

Internationally adopted children face greater risk of possible exposure to infectious diseases (Chen, Barnett, & Wilson, 2003; Lebner, 2000) or other illness, malnutrition (Altemeier, 2000), or failure to thrive, which adoptive parents may not be fully aware of or prepared for at the time of adoption. Many children may display developmental delays or cumulative cognitive deficits depending on their age, the impact of the quality of care they have received prior to adoption, or the length of pre-adoption institutionalisation (Juffer et al., 2005; Mason & Narad, 2005; Serbin, 1997; Weitzman & Albers, 2005). These children face learning a new language under great communicative pressure and are likely to need specialised assistance in developing the particular knowledge essential to thriving in their new cultural context (Gindis, 2005; Mohanty & Newhill, 2005). Sensitive and timely preschool placement and long-term remediation are crucial (Caro & Ogunnaike, 2001; Costello, 2005; Gindis, 2005). Children’s developmental outcomes can often be significantly improved by access to family and community services and resources in the postadoption period (Barnett & Miller, 1996; Bledsoe & Johnston, 2004; Caro & Ogunnaike, 2001; Galvin, 2003; Groza et al., 2003; Haradon, 2001; Mohanty & Newhill, 2005).

Dealing with issues of culture and identity

Many studies report international adoptees’ confusion about their race, ethnicity, and cultural identity, and experiences of racism and discrimination (Mohanty & Newhill, 2005; Silverman, 1997; Vonk, 2001). Although in most situations a child’s culture has a positive meaning and helps a child to identify with others and define him- or herself, in the case of international adoption, culture may have both positive and negative meanings for the child, because an internationally adopted child’s cultural background may be closely related to experiences of loss, deprivation, or abuse (Benson, Sharma, & Roehlkepartain, 1994; Mohanty & Newhill, 2005; Silverman, 1997; Vonk, 2001). Ethnic identification and pride play an important role in the development of positive self-esteem and overall psychological adjustment and can serve as a protective factor against behavioral problems, particularly during adolescence (Mohanty & Newhill, 2005). Research suggests that internationally adopted children adjust better if they are provided with a nurturing environment that openly acknowledges the physical differences they may have from their adopted family or peers. It is also helpful if internationally adopted children are exposed to positive role models from their countries of origin, and if acknowledgment is given to the psychological similarities between themselves and their new family and country (Mohanty & Newhill, 2005; Trolley, Wallin, & Hansen, 1995; Vonk, 2001). Cultural competence on the part of the adoptive parents is critical, and the internationally adopted child’s self-esteem is often positively correlated to parental cultural competence and the extent to which children are exposed to their culture of origin. Further research is required to fully understand the exact mechanisms of positive adjustment in internationally adopted children and to better operationalise the construct of cultural competence. To strengthen internationally adopted children’s adaptive psychosocial functioning, family support services should be sensitive to issues which may undermine parental support for the child’s identity (Feigelman & Silverman, 1984).

Implications for policy, research, and practice

Social policy changes in adoption processes within the United States, the protection of parental rights, and the provision of legislative and welfare support to keep young children with their biological parents in all reasonable circumstances and to encourage open adoptions have resulted in fewer young, healthy children being available through public and private adoption systems within the United States (Johnson, 2005; O’Halloran, 2006). In the 2002 national survey of attitudes about adoption (Harris Interactive, Inc., 2002, p. 29), 84% of respondents stated that, if they were thinking about adopting, a major concern would be making sure that birth parents could not take the child back. Many prospective parents felt they wanted to adopt the child, not the child’s family nor the problems that prompted the adoption process in the first place (Johnson, 2005).

The development of increased maternal and paternal rights in the United States is aligned with the international principles established by the Hague Convention that champion the right of children to be raised by their birth parents in their birth cultures and countries unless compelling circumstances dictate otherwise. To some extent, the wealth—and the social policy protection associated with that wealth—of the United States has protected these rights for its youngest citizens. Yet this circumstance—although perhaps inadvertently—has created a demand for younger, healthier children accessed from outside the country through closed adoption with a greater and greater frequency from somewhat poorer countries that are less or not able to provide their children with such protections (Hollingsworth, 2003; Wallace, 2003).

Although there can be no disputing that adoption presents a healthier and more successful option for children without family care than any nonpermanent social program (Bartholet, 1993), we need to ask whether international adoption reduces political will to develop systems that encourage and support domestic adoption in more prosperous sending countries (as evidenced in South Korea) or exploits the inability of poorer countries to do so while providing for the parenting and family-building needs of western society. The fact that countries such as South Korea, China, Thailand, and the former communist states of Eastern Europe are sending children to the United States and Sweden despite having birth levels below replacement level warrants both political and ethical consideration (Kane, 1993; Selman, 2002; Weil, 1984).

In contrast, international adoption as a means of family building is proving to be fairly successful for American adopters. Younger, healthier children from closed adoptions from other countries are better adjusted than domestically adopted children (Miller, 2005b). A recent large meta-analysis (Juffer et al., 2005) of the behavioral and mental health outcomes in internationally adopted children suggests that most internationally adopted children are well adjusted. Even though they are more frequently referred for mental health services than their nonadopted peers (Juffer et al., 2005), international adoptees have fewer behavior problems and are less frequently referred to mental health services than domestically adopted children (Juffer et al., 2005). Trends indicating that the demand for younger children is more frequently being met through international adoption (Johnson, 2005) at the expense of domestically available older children (O’Halloran, 2006) should give us pause for thought.

Concluding thoughts

Superstar Angelina Jolie, despite critiques of her family building activities, in fact models quite well the Hague requirements for preserving a child’s cultural heritage by ensuring that her children have frequent contact with their birth culture and country, and by drawing attention to the needs of children in their countries of origin. Critics would be hard pressed not to concede that she has met the international standards enshrined by the Hague Convention. The questions is to what extent the average international adopter in the United States can afford, or is willing and able, to do the same.

It is often argued that the practice of international adoption helps to save children from a life of institutionalisation, but in reality very few institutionalized children in sending countries benefit from international adoption. International adoption does little to change the status quo or encourage and support the development of family preservation or domestic adoption systems in sending countries. It is quite possible that international adoption may be courting inertia around developing adequate child welfare programs in sending countries (Hollingsworth, 2003; Selman, 2002; Wallace, 2003).

Although in no way invalidating the rights of individual children to a better and more stable family life, we must acknowledge our responsibility to strive for the same conditions and opportunities for all children regardless of the country of their birth. In advocating for a better world for all children, an important first step is to raise awareness and attention of the complexities within the debate surrounding international adoption and to advocate, with the hindsight and wisdom afforded to us by history, for a deeper, more complex, and realistic perspective of what may be in “the best interests of the child” within these debates.

References

Altemeier, W. A. (2000). Growth charts, low birth weight, and international adoption. Pediatric Annals, 29, 204–205.

Altstein, H., & Simon, J. (1991). Intercountry adoption: A multinational perspective. New York: Praeger.

Bainham, A. (2003). International adoption from Romania: Why the moratorium should not be ended. Child and Family Law Quarterly, 15, 223–236.

Barnett, E. D., & Miller, L. C. (1996). International adoption: The pediatrician’s role. Contemporary Pediatrics, 13, 29–48.

Bartholet, E. (1993). International adoption: Current status and future prospects. Future of Children, 3, 89–103.

Benson, P. L., Sharma, A. R., & Roehlkepartain, E. C. (1994). Growing up adopted: A portrait of adolescents and their families. Minneapolis: Search Institute.

Bledsoe, J. M., & Johnston, B. D. (2004). Preparing families for international adoption. Pediatrics in Review, 25, 242–250.

Caro, P., & Ogunnaike, O. (2001). International adoption: Strategies in early childhood classrooms to help facilitate family success. The Journal of Early Education and Family Review, 9, 6–10.

Chen, L. H., Barnett, E. D., & Wilson, M. E. (2003). Preventing infectious diseases during and after international adoption. Annals of Internal Medicine, 139, 371–378.

Costello, E. (2005). Complementary and alternative therapies: Considerations for families after international adoption. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 52, 1463–1478.

D’Amato, A. (1998). Cross-country adoption: A call to action. Notre Dame Law Review, 73, 1239–1249.

Darnell, C. L. (2004). “I wanted a baby so bad”: A look at international adoption. Healing Magazine, 9, 12–14.

Diamond, G. W., Senecky, Y., Schurr, D., Zuckerman, J., Inbar, D., Eidelman, A., et al. (2003). Pre-placement screening in international adoption. IMAJ, 5, 763–766.Feigelman, W., & Silverman, A. R. (1984). The long term effects of transracial adoption. Social Service Review, 58, 588–602.

Fieweger, M. E. (1991). Stolen children and international adoption. Child Welfare, 70, 285–291.

Galvin, K. (2003). International and transracial adoption: A communication research agenda. Journal of Family Communication, 3, 237–253.

Gindis, B. (2005). Cognitive, language and educational issues for children adopted from overseas orphanages. Journal of Cognitive Education and Psychology, 4, 290–315.

Gold, A. L. (1996). Factors pre and post adoption associated with attachment relationships between international adoptees and their adoptive parents. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Toronto, Canada.

Goldberg, S., & Marcovitch, S. (1997). International adoption: Risk, resilience, and adjustment. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 20, 1–2.

Groza, V., & Ryan, S. D. (2002). Pre-adoption stress and its association with child behavior in domestic special needs and international adoptions. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 27, 181–197.

Groza, V., Ryan, S. D., & Cash, S. J. (2003). Institutionalization, behavior and international adoption: Predictors of behavior problems. Journal of Immigrant Health, 5, 5–17.

Haradon, G. L. (2001). Facilitating successful international adoptions: An occupational therapy community practice innovation. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 13, 85–99.

Harris Interactive, Inc. (2002). National adoption attitudes survey: Research report. Retrieved April 19, 2007, from www.adoptioninstitute.org/survey/Adoption_Attitudes_Survey.pdf

Hollingsworth, L. D. (2003). International adoption among families in the United States: Considerations of social justice. Social Work, 48, 209–217.

Johnson, D. E. (2005). International adoption: What is fact, what is fiction, and what is the future? Pediatric Clinics of North America, 52, 1221–1246.

Juffer, F., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2005). Behaviour problems and mental health referrals of international adoptees: A meta-analysis. JAMA, 293, 2501–2515.

Kane, S. (1993). The movement of children for international adoption: An epidemiologic perspective. Social Science Journal, 30, 323.

Lebner, A. (2000). Genetic “mysteries” and international adoption: The cultural impact of biomedical technologies on the adoption family experience. Family Relations, 49, 371–377.

Levy-Shiff, R., Zoran, N., & Shulman, S. (1997). International and domestic adoption: Child, parents, and family adjustment. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 20, 109–129.

Mason, P., & Narad, C. (2005). International adoption: A health and developmental prospective. Seminars in Speech and Language, 26, 1–9.

Miller, L. C. (2005a). Immediate behavioral and developmental considerations for internationally adopted children transitioning to families. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 52, 1311–1330.

Miller, L. C. (2005b). International adoption, behavior, and mental health. JAMA, 293, 2533–2535.

Mohanty, J., & Newhill, C. (2005). Adjustment of international adoptees: Implications for practice and a future research. Children and Youth Services Review, 28, 384–395.

Momaya, M. L. (1999). Motivation towards international adoption. Unpublished master’s thesis, California State University, Long Beach.

O’Halloran, K. (2006). The politics of adoption: International perspectives on law, policy & practice. The Netherlands: Springer.

Selman, P. (2002). Intercountry adoption in the new millennium: The “quiet migration” revisited. Population Research and Policy Review, 21, 205–225.

Rosenblum, K., & Olshansky, E. (2007). Creating a family: Diverse pathways to parenthood. Zero to Three, 27(5).

Serbin, L. A. (1997). Research on international adoption: Implications for developmental theory and social policy. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 20, 83–92.

Shapiro, V., Shapiro, J., & Paret, I. (2001). International adoption and the formation of new family attachments. Smith College Studies in Social Work, 71, 389–418.

Silverman, B. (1997). Cultural connections in international adoption. Adoption Therapist, 8, 1–4.

Trolley, B. C., Wallin, J., & Hansen, J. (1995). International adoption: Issues of acknowledgement of adoption and birth culture. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 12, 465–479.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2007). United States census 2000. Available from United States Census 2000 Gateway, www.census.gov/main/www/cen2000.html

U.S. Department of State (2007a). Significant source countries of immigrant orphans (totals of IR-3 and IR-4 immigrant visas issued to orphans) fiscal years 1992–2004. Available from Bureau of Consular Affairs, travel.state.gov/visa/frvi/statistics/statistics_2541.html

U.S. Department of State. (2007b). Significant source countries of immigrant orphans (totals of IR-3 and IR-4 immigrant visas issued to orphans) fiscal years 1996–2005. Available from Bureau of Consular Affairs, travel.state.gov/visa/frvi/statistics/statistics_2541.html

Vonk, M. E. (2001). Cultural competence for transracial adoptive parents. Social Work, 46, 246–255.

Wallace, S. R. (2003). International adoption: The most logical solution to the disparity between the numbers of orphaned and abandoned children in some countries and families and individuals wishing to adopt in others? Arizona Journal of International & Comparative Law, 20, 689–724.

Weil, R. H. (1984). International adoptions: The quiet migration. International Migration, 18, 276–293.

Weitzman, C., & Albers, L. (2005). Long-term developmental, behavioural, and attachment outcomes after international adoption. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 52, 1395–1419.

Wittner, K. M. (2003). Curbing child-trafficking in intercountry adoptions: Will international treaties and adoption moratoriums accomplish the job in Cambodia? Pacific Rim Law & Policy Journal, 12, 595–629.

Copyright 2010, ZERO TO THREE. All rights reserved. For permission to reprint, go to www.zerotothree.org/reprints

Zero to Three Corner. International Adoption: Benefits, Risks and Vulnerabilities

Authors

Rochat, Tamsen,

Richter, Linda,

Child, Youth, Family and Social Development Programme,

Human Sciences Research Council,

South Africa