Introduction

The impact of investing in early childhood development is paramount for the development of any country (Heckman, 2000). It is imperative that institutions that are home to young children outside of parental care, arguably the most at risk population in early childhood, be part of any national plan for early childhood development. Defining the numbers of children who are orphaned or without permanent parents is a worldwide challenge because of the lack of a consistent definition of the status of these children, lack of documentation on these children and lack of resources to monitor these children and the care they receive. Approximately 88% of children labeled as “orphans” by international agencies have been found to have one living parent (Sherr, Varrall, Mueller, Richter, Wakhweya, Adato, & Desmond, 2008), but regardless these children are part of the child protection system.

Today, there is a strong international movement to prevent children from entering protection systems, to increase family reunification or adoption and to shift those children still in the system from institutional to family based care. There are, however, many factors leading to children’s placement in institutions and in the protection system. These factors, such as poverty, disease, social factors and violence, are major international challenges that are far from being resolved, and pose obstacles to transitions to families regardless of whether children have living parents.

While there is much international effort made to confront these major challenges, each country is ultimately sovereign and governments make independent decisions weighing cultural, political and economic (among others) factors. Despite pressure from the international community, resources will be dedicated and problems will be addressed as each country deems fit. Barriers in reaching the ideal protection system for children are in many ways similar to other international challenges and include a mix of internal and external politics, historical experiences and simple resource availability and allocation. The same lack of resources that limits a government’s knowledge of exactly how many children are outside of family care also limits its ability to monitor and evaluate existing care–whether institution or family based. In many countries, governments do not currently take fiscal responsibility for children without guardianship and their care–a role filled largely by non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Not having control of the funding in this climate of minimal resources, nascent foster care systems suffer from the same lack of training that institutions do, but with less accountability and less support. Even where resources are more available, children in poor foster care have been shown to be more likely to develop behavioral, educational, and emotional problems than children who are raised by abusive and high-risk parents (Jones Harden, 2004; Lawrence, Carlson, & Egeland, 2006). Simply placing a child in foster or family based care does not ensure quality nor protection of the child.

If countries do have enough resources to begin a comprehensive overhaul of their foster care system, children will still continue to spend some time in institutional care, as they do in countries where there is an established foster care system. Even if children are in transition to family based care or adoption, the impact this time can have in early childhood is enormous. A positive experience in this institutional care period can improve and even facilitate children’s positive integration to families and society; a negative experience can have lifelong detrimental effects (Bruskas 2010; Jones Harden, 2004; Cassidy & Berlin 1994).

Approximately 31.4% of the population in Latin America is described as living in poverty unable to meet basic needs including food, shelter, clothing, water and sanitation, education, and healthcare and at risk for violence (Social Development Division and the Statistics and Economic Projections Division of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, 2012). This developing region is home to approximately 12 million orphans, the equivalent to approxiamtely 6% of the total population (United Nations Children’s Fund, 2009). As elsewhere, the vast majority of Latin American children’s institutions are ill-prepared to receive children, lacking the fundamental infrastructure support systems required for healthy socio-emotional development and plagued with caregiving practices that create more psychological distress (Rosas & McCall, 2009). Evidence demonstrates that children under the age of three are particularly vulnerable to developmental delays when not provided with appropriate care and attention (Johnson, 2000; Smyke, Koga, Johnson, Fox, Marshall, Nelson, Zeanah, the BEIP Core Group, 2007). More importantly, there is a strong body of international evidence that shows the positive effects of quality care and attention (Baker-Henningham & Lopez Boo, 2010; Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University, 2007; David & Appell, 2001).

The impact of poor caregiving and poor institutional care is far reaching. Research has been consistent in demonstrating that stressful experiences in childhood are pathways toward poor outcomes in adulthood, including premature mortality, disease, disability, antisocial behaviors and serious mental health problems (Caspi, Henry, McGee, Moffitt, & Silva, 1995; Felitti et al., 1998; Whitaker, Orzol, & Kahn, 2006). These poor outcomes have high cost implications for any society and contribute to intergenerational transmission of poverty, poor health and development. Meanwhile, research suggests that perhaps as much as 50% of the impact of stress and risk factors can be mitigated with targeted caregiving (Duncan & Brooks-Gunn, 2000). Early childhood education programs have been shown to have the potential to generate government savings that more than repay their costs and produce returns to society as a whole that outpace most public and private investments (Kilburn & Karoly, 2008). Programs that address early childhood development, especially for children at risk, have consistently shown the significant benefit of investments in young children, while failing to invest is costly to families, communities, businesses and nations (Cobb, 2003). There are no studies on the return of investment for child protection centers, though the costs associated with adults who have received poor institutional care are well documented (Tobis, 2000; Penglase, 2005). For developing countries the promise of return on investment in early childhood is more than a moral imperative, it is a path out of poverty.

There are studies of the development of children at risk in Latin America (BakerHenningham, & Lopez Boo, 2010; Green, 1998; Raffaelli, 1999), and studies on positive outcomes for children removed from institutional care (Smyke, et al, 2007; Nelson, Zeanah, Fox, Marshall, Smyke, & Guthrie, 2007), but few studies exist internationally on the impact of intentional improvement of care for children in institutions (David & Appell, 2001; Smyke et al., 2007; McCall, Groark, Fish, Harkins, Serrano, & Gordon, 2010; Sparling, Dragomir, Ramey, & Florescu, 2005; The St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team; 2005; Vorria, Papaligoura, Dunn, Van IJzendoorn, Steele, Kontopoulou, 2003; Dobrova-Krol, Van IJzendoorn, BakermansKranenburg, & Juffer, 2010). Prior to this effort to systematically improve and assess institutions and caregivers in Nicaragua, no studies existed on the impact of Latin American institutions on children’s development.

Background to Case Study

Whole Child International (WCI) was created in 2004 as a not-for-profit nongovernmental organization, with a mission to improve the quality of care for children, prioritizing those children most at risk i.e. those residing in institutions, and those at risk in early childhood. WCI was founded with the belief that there are simple cost effective ways to improve existing institutions and the quality of care they provide using existing resources. Inspired by developmental research such as the Pikler Institute experience (David & Appell, 2001) and Bowlby’s Attachment Theory (Bowlby, 1958), as well as current brain research that affirms a secure and caring one-to-one relationship between a caregiver and a young child coupled with adequate nutrition is the most critical component for healthy cognitive, physical, and socio-emotional development (Schore, 2001), WCI aims to improve quality of care to meet the highest standards in child development through the same evidenced based best practices recommended for any early childhood intervention, applied to limited resource settings.

Nicaragua

Nicaragua has a population of 5,727,707 with 31.7% under 14 years of age, and is the second poorest country in Latin America and the Caribbean after Haiti with a per capita gross domestic product of 7.08 billion dollars (Central Intelligence Agency, 2013). Nicaragua’s high poverty rates especially affect vulnerable groups such as children. It is estimated that about 114,000 children live in extreme poverty and 25,000 children and teenagers live on the street. Over 3,000 children and adolescents are currently being placed in child protection centers, called Protection Centers, either because of orphanhood, abandonment or the application of special protection measures established in the Children’s and Adolescent’s Code (Government for Reconciliation and Unity of Nicaragua, 1998). Enforcing the Code and ensuring quality of care in the child protection centers is a serious challenge for the Ministry of Family Adolescence and Children (MIFAN), the institution charged with oversight of the child protection system. MIFAN suffers from scarce financial and human resources. Only 1 out of approximately 85 child protection centers is public (the rest are run by nongovernmental and religious organizations) and only 30 of the private child protection centers receive some form of partial state subsidy through MIFAN (Ministerio de la Familia Adolescenia y Niñez, 2012). The exact number of child protection centers and the quality of the care they provide is unknown and unregulated due to this same lack of resources in MIFAN and lack of attention by greater non-governmental organization community. Government officials responsible for child protection centers and early childhood programs changed frequently through the early years of WCI’s work, only reaching some stability during the two years of the Technical Cooperation (2010-2012), when the largest successes were achieved.

Intervention Overview

In 2006, WCI began implementation of a multifaceted intervention consisting of intensive training, low cost improvements to the physical environment, and policy and regulatory reform in Nicaragua. First, WCI began its work through a pilot program with MIFAN in the one state run child protection center (Groark, McCall, Fish, & the Whole Child International Evaluation Team, 2008) and later under a Technical Cooperation with the InterAmerican Development Bank under the Korean Poverty Reduction Fund (#ATN/KP/12327-NI).

The premise of the WCI intervention is centered on the minimum set of conditions needed to ensure that every child’s basic psychological needs are met-by focusing on four fundamental areas of evidence based best practices. These four practice areas are: 1) supporting an organizational structure that will sustain a primary relationship between caregiver and child; 2) improving the quality of interaction between caregiver and child; 3) ensuring that the physical space supports child development; and 4) ensuring that each child’s own sense of being an individual is honored. WCI’s intervention is designed to provide for children’s socio-emotional wellbeing through a series of cost-effective interventions. The four practice areas are addressed through three intervention components: a) government training and collaboration; b) organizational training and change; and c) academic training and development.

WCI intentionally works with the existing resources of institutions, teaching them to more effectively use resources at their disposal to the benefit of the children in their care. WCI does not intend to take over the responsibility for institutions or their functioning. It is important to note that this intervention does not address nutrition and throughout the entire intervention there was no change in the nutrition that children received (Groark et al., 2008; Groark et al., in press). Addressing the challenge of accessibility of quality in early childhood care in severely limited resource settings, WCI focuses on the technical guidance and training for the professionalization of early childcare staff in limited resource settings through a train the trainer approach. A key goal of the overall intervention is to create local capacity at every level, lowering the cost of implementation, and ensuring the sustainability of the work.

Method

Sample

WCI worked with five child protection centers ranging in population from 13 children in the smallest child protection centers to 79 in the largest. Children residing at these institutions ranged in age from birth to 6 years old and included children with mild to severe special needs. One child protection center was tracked over the course of 6 years; the remaining four were tracked over the course of 2 years. The populations in each orphanage varied over the course of study related to various attrition factors. The inclusion criteria for child protection centers were the primary child protection centers in the capitol city that care for children birth to 6 years of age.

Procedures

WCI trained caregivers and other child protection center staff (e.g., administrative staff, cleaning staff, cooking staff, security guards, etc.) through their signature caregiver training program. This program combines interactive classroom trainings on topics such as positive communication, routine care and interactions, environment and materials, observation, freedom of movement, value of play, neuroscience and cognitive development, and professional care and boundaries, with on-site oneon-one technical assistance provided by local staff. WCI also trained government and child protection center staff in Nicaragua’s first university level course on early childhood care developed with Loyola Marymount University and The School of Public Health of the National Autonomous University of Nicaragua (Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios de la Salud, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Nicaragua, Managua).

WCI worked closely with the administrative and supervisory staff of the child protection centers to increase the likelihood of success in application of what they learned through the various intervention activities. Some activities were purely administrative such as the essential development of regular caregiver schedules and assignments in order to maintain consistent care with the same children (Shabazian & Lopez, 2011). Other activities included necessary physical improvements to each child protection center including providing child size furniture (e.g., beds, cribs, tables, chairs and rockers), introducing child safety gates, and creating protected play spaces for the younger children. The intent of these furnishings was to help facilitate caregiver-child interactions during routines (David & Appell, 2001) while assuring that other children have space to move freely within a safe area. WCI also created developmentally appropriate environments by adding soft spaces, loft play structures, and sand boxes.

Perhaps the largest and one of the most unique aspects of Whole Child’s Intervention has been the focus on intensely developing the relationship between the caregiver and a mentor (the WCI local trainers assigned to each child protection center). The mentoring activity, termed “technical assistance”, was performed almost exclusively by the local trainers to ensure clear and culturally respectful communication. The child protection centers themselves did not provide any training or orientation for new staff prior to intervention.

Before beginning technical assistance the WCI mentors observed each caregiver for approximately an hour and evaluated her level of independence in successful implementation of sensitive and respectful caregiving based on Gray and Gray’s (1985) mentoring scale (see Addendum). Local trainers were cautioned not to evaluate caregivers as «good» or «bad» but rather to assess their level of comprehension and independence in application of quality caregiving based on their actions and activities. This information was then compiled with the entire technical team and the first week of technical assistance hours were allotted based on the ratings, i.e. a caregiver who rates a «P» or Level 5 will only require minimum follow up for answering questions and confirming the rating a task that can be done with an hour or less of observation, whereas a caregiver that is rated a «Mp» or Level 2 shows signs of having participated in training but is not successfully or independently implementing the concepts and may need several hours in each of her shifts. Ratings were reassessed in every instance of Technical Assistance and the information was compiled and analyzed by the WCI technical team in weekly team meetings to re-allot hours of technical assistance for the coming week. Technical assistance was never given for greater than a 2 hour block at a time though it was occasionally given in multiple 1 hour blocks, though never greater than three 1 hour blocks in 1day. This individualized the amount of time that each caregiver received based on her needs and ability to independently apply the concepts learned. All caregivers received at least 1 hour of technical assistance every week (and some received as much as 15 hours), which required some WCI staff to work on «off» hours including very early morning, late evening, or weekends.

Mentoring activities varied based on the activities during the time of mentoring, and the level of independence of the caregiver. Technical assistance included: answering questions to clarify concepts, answering application questions for specific situations that arose, asking the caregiver questions regarding her practice, probing the caregiver to reflect on her practices, and modeling interactions with children. Local trainers received specific training and feedback on their performance in these areas (both «staged» beforehand and «live» with a caregiver) from the WCI Technical Supervisors, Expert Trainers, Expert Technical Consultant and Country Director. Local trainers were specifically instructed to respect the role of the caregiver with the children–in no way to diminish that role by becoming a supervisor or judge, rather to defer to the caregiver and provide feedback in more opportune moments except if a child was in imminent physical danger. Supervisors at each center (director, technical team) were updated at least monthly by the WCI technical team on the progress of the caregivers with specific positive examples of growth and moments that continued to be challenges.

After the 9 months of caregiver training passed, the WCI technical team reobserved every caregiver on all 19 objectives of the caregiver training to provide an overall rating with areas for continued improvement. At this time additional mini trainings specific to each center were provided if there was a concept that many caregivers were not performing independently. In some cases this was a review of the same information presented in the WCI Caregiver Training program, in other instances training was provided on working with children with special caregiving needs. In the first few weeks after the end of the formal WCI Caregiver Training, technical assistance time was more evenly distributed between all caregivers in that most caregivers did have an area they could continue to improve upon. After a month, technical assistance time became more focused on the caregivers that continued to struggle for independent application.

Results

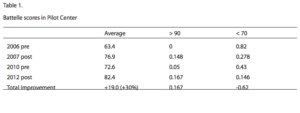

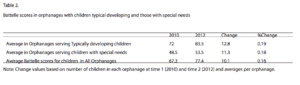

Within 4 months of WCI’s collaboration with the centers, children demonstrated marked increases in their developmental milestones and those children that had participated in the pilot program showed an average improvement of 13% in their scores since the start of the intervention (Groark et al., 2008). Scores also demonstrated an improvement in the quality of care that children received: caregivers displayed warmer, sensitive, and responsive interactions with children; children’s development in all domains (cognitive, language, physical, and socialemotional) improved (Groark et al., in press). (See Table 1 and 2).

Since 2006, children in the pilot child protection center improved on average 30 points on the Battelle Development Index, with the number of children scoring under 70 (i.e., presenting as if diagnostically intellectually disabled, though they are not) decreasing by 62%. Children with special needs were especially positively impacted by the intervention with percentage change of improvements on the Battelle Development Index similar to typically developing children. Height rose on average from the 8th to the 54th (cross sectional) percentile, and weight rose on average from the 5th percentile to the 30th (cross sectional) percentile. (See Table 1 and 2)

Discussion

The three areas of greatest challenge and simultaneously greatest success were government collaboration, technical assistance and sustainability. First, though WCI enjoyed a positive relationship with the government throughout the intervention, there was no regulatory guidance monitoring or evaluation of the child protection centers independent of WCI efforts. The WCI intervention did not require a monetary investment from MIFAN. Coupled with the pervasive lack of resources at MIFAN, and the push to close child protection centers championed at the international level, for much of the early years of the WCI intervention there was little government interest. There was renewed interest and increased collaboration with WCI following a wave of adoptees being returned from their adoptive families, closing child protection centers following information of the quality of care being shared with MIFAN, the reopening of child protection centers to be able to accommodate the influx of children, and the increased attention to poor the care being provided for children with special needs.

WCI and MIFAN did eventually collaborate on one major lasting achievement: the inclusion of best practices in the policies governing early childhood care in Nicaragua via the National Early Childhood Policy and the Norms for Restitution of rights and special protection for girls, boys and teens. This document was prepared by a graduate of WCI’s university course who is a MIFAN director responsible for all programs for children 0-6 years of age. The policy includes many of the topics covered in the WCI university course including the children’s rights perspective in program planning, caregiver and staff preparation and training, keeping siblings together, consistency of caregivers, value of attachment, and definition of small groups of care. Though this new policy has not been fully implemented, the inclusion of these topics which had not previously been discussed on the national agenda was a major sustainable accomplishment and helped highlight the success of the WCI intervention. Many child protection centers have already been voluntarily implementing the new norms based on the WCI recommendations).

A second major challenge was found in providing technical assistance. The concept of having a mentor for a job they had been doing for in some cases more than 20 years was at first difficult for staff to comprehend. While WCI staff was able to engender trust, it became clear that WCI staff needed further training on mentoring, professional coaching and technical assistance. It was also difficult for child protection center staff to reconcile suggestions given by WCI trainers that did not always match with those given by their own supervisors, who were learning as they went through WCI trainings as well. Supervisor support for interventions dramatically improved over the course of the University course; future interventions will incorporate a restructuring of the training time line.

The third major challenge was sustainability. WCI has been committed to the strengthening of local capacity from its inception. During the intervention, WCI restructured our staffing plan and provided greater preparation to the local trainers. By leveraging the supervisory role of the child protection center leaders through their participation in the University course with the guidance from WCI trainers, WCI was able to reduce our role in the major task of directly advising caregivers. This enabled the WCI staff to focus more on helping supervisors figure out how to enact the necessary changes and mentor their own staff, required to build local capacity to ensure sustainability. Future interventions will continue with an even more aggressive transfer of responsibility to child protection center staff through supporting their development of monitoring and evaluation skill sets.

The choice of having local trainers provide all mentoring activities, with outside experts providing guidance to them, was intentional. Requesting that all child protection center staff (not just caregivers) attend all trainings to engender a pervasive understanding of the role of the child protection center in fostering positive development for all children was also deliberate. These efforts were demonstrated to be successful by children’s improvement in the pre and post intervention evaluations. However, from the time of the first post intervention evaluation in 2007 to the next evaluation in 2010, though scores did not dip to their pre-intervention levels, they were not maintained near the level of the post intervention evaluation. The drop in scores and increase in caregiving challenges when centers reverted back to unstable groups with variable caregivers served as a poignant reminder to centers the difference between what the successes had been when best practices were successfully implemented and typical institutional care.

Limitations

This study used pooled cross-sectional data, a collection of cross-section datasets observed at different points in time. In this case, data were collected at the two child protection centers in 2010 and then in 2012, with different subject groups. The analysis consisted of comparing the differences between the subject groups. The limitation of using pooled crosssectional data lies in the fact that the same subjects are not followed over time and therefore it is difficult to establish causality.

Further limitations involve the reliability, validity and generalizability of case studies. As this case study focuses on a single intervention in one country, the issue of generalizability is greater than with other types of qualitative research. Another concern regarding case study research is an ethical one, which is introduced by the subjectivity of the researcher. Case studies are based on the analysis of qualitative data, which requires the researcher to interpret the findings and leaves room for personal bias.

Conclusion and Future Implications

The work of WCI is focused on exploring the possibility of improving resource limited institutions in a cost effective, culturally sensitive manner. Attention given to the problem of vulnerable children outside of family care must incorporate the improvement of the institutions themselves as, despite the best efforts of all involved, children will spend time in these places, sometimes most of their formative years. As we seek to solve the problem of providing care for children outside of family care, especially in limited resource settings, there is value in investing in child protection center s and institutions and the children that reside and receive care there. For many governments of developing countries implementing a new child protection system or radically overhauling the existing system will take too much money and time, and is not part of plans in the foreseeable future. Especially when they do not currently shoulder the fiscal responsibility for children outside of family care, many of whom are cared for in institutions funded by NGOs and religious organizations.

This case study seeks to serve as a counter point to “The Bucharest Early Intervention Project” (Smyke et al., 2007) where it was shown that trained foster care was superior and provided a more positive development experience for children than typical institutional care. Well prepared, supported and monitored foster care is simply not likely to happen in the foreseeable future in much of the developing world. The dichotomy need not be quality (un-attainable) foster care or poor institutional care. There is another cost effective, realistic option. Implementing national regulations and improving the quality of the institutions themselves, as WCI has done, is cost effective and sustainable, though ideally temporary.

Future research should take the lessons of the BEIP and WCI intervention and look to isolate the components to better understand exactly which factors contribute most to children’s over all wellbeing. The focus should not be on the walls within which children live, but the relationships that help them do so.

The period of early childhood is crucial in lifelong development. The success of these most vulnerable children is the key to responsible development, a path out of poverty, and will ultimately lead to greater international stability.

References

Baker-Henningham, H., & Lopez Boo, F. (2010). Early childhood stimulation interventions in developing countries: A comprehensive literature review series. Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank.

Bowlby, J. (1958). The nature of the child’s tie to his mother. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, XXXIX, 1-23.

Bruskas, D. (2008). Developmental health of infants and children subsequent to foster care. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 23(4), 231-241. doi: 10.1111/j.1744- 6171.2010.00249.x

Caspi, A., Henry, B., McGee, R., Moffitt, T., & Silva, P. (1995). Temperamental origins of child and adolescent behavior problems from age three to age fifteen. Child Development, 66, 55-68. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995. tb00855.x

Cassidy, J., & Berlin, L. J. (1994). The insecure/ambivalent pattern of attachment: Theory and research. Child Development, 65(4), 971–991.

Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. (2007). A Science-based framework for early childhood policy: Using evidence to improve outcomes in learning, behavior, and health for vulnerable children. Retrieved from https://developingchild.harvard.edu/index.php/resources/reports_and_working_papers/policy_framework/

Central Intelligence Agency. (2013). The world fact book: Nicaragua. Retrieved from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/nu.html

Cobb, K. (2003). The ABCs of early childhood development: A discussion on the economics of early childhood development. The Region, 17(4), 1-5. Retreived from https://www. minneapolisfed.org/publications_papers/pub_display.cfm?id=3351

David, M., & Appell, G. (2001). Loczy, an unusual approach to mothering. Budapest: Association Pikler-Loczy for Young Children.

Dobrova-Krol, N. A., Van IJzendoorn, M. H., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & Juffer, F. (2010). Effects of perinatal HIV infection and early institutional rearing on physical and cognitive development of children in Ukraine. Child Development, 81(1), 237-251. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01392.x

Duncan, G. J., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2000). Family poverty: Welfare reform and child development. Child Development, 71, 188-196. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.40.5.727

Felitti, V. J., Anda , R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245-258. doi:10.1016/S0749- 3797(98)00017-8

Government for Reconciliation and Unity of Nicaragua. (1998, May 27). Law 287- 98 Código de la Niñez y Adolescencia. Approved el 24 de Marzo de 1998. Published in La Gaceta No. 97.

Gray, W. A. & Gray, M. M. (1985). Synthesis of research on mentoring beginning teachers. Educational Leadership, 43(3), 37-43.

Green, D. (1998). Hidden lives: Voices of children in Latin America and the Caribbean. London: Cassell.

Groark, C. J., McCall, R. B., Fish, L, & the Whole Child International Evaluation Team. (2008). Managua orphanage baseline report. Retrieved from https://www.ocd.pitt.edu/Files/ PDF/managuaorphanage.pdf

Groark, C. J., McCall, R. B., McCarthy, S. K., Eichner, J. C., Warner, H. A., Salaway, J., & Palmer, K. (in press). The effects of a social-emotional intervention on caregivers and children in five Central American institutions. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Office of Child Development. Prepared for: Whole Child International and the InterAmerican Development Bank.

Heckman, J. J. (2000). Policies to foster human capital. Research in Economics, 54(1), 3-56.

Johnson, D. E. (2000). Medical and developmental sequelae of early childhood institutionalization in Eastern European adoptees. In C. A. Nelson (Ed.), The effects of early adversity on neurobehavioral development: The Minnesota symposium on child psychology series(pp. 113-162). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Jones Harden, B. (2004). Safety and stability for foster children: A developmental perspective. The Future of Children, 14 (1), 31-47. Retrieved from https://futureofchildren.org/futureofchildren/publications/docs/14_01_02.pdf

Kilburn, M. R., & Karoly, L. A. (2008). The economics of early childhood policy: What the dismal science has to say about investing in children. Retrieved from https://www.rand.org/pubs/occasional_papers/OP227.html

Lawrence, C., Carlson, E., & Egeland, B. (2006). The impact of foster care on development. Development and Psychopathology, 18, 57-76. doi:10.10170S0954579406060044

McCall, R. B., Groark, C. J., Fish, L., Harkins, D., Serrano, G., & Gordon, K. (2010). A social-emotional intervention in a Latin American Orphanage. Infant Mental Health Journal, 31(5), 521-542. doi:10.1002/imhj.20270

Ministerio de la Familia Adolescencia y Niñez. (2012). Acreditación a centros de protección social y especial. Retrieved from https://www.mifamilia.gob.ni/?page_id=249

Nelson, C. A., Zeanah, C. H., Fox, N. A., Marshall, P. J., Smyke, A. T., & Guthrie, D. (2007). Cognitive recovery in socially deprived young children: The Bucharest Early Intervention Project. Science, 318(5858), 1937-1940. doi:10.1126/science.1143921

Penglase, J. (2005). Orphans of the Living: Growing up in care in twentiethcentury Australia. Perth: Curtin University Books.

Raffaelli, M. (1999). Homeless and working street youth in Latin America: A developmental review. Interamerican Journal of Psychology, 33(2), 7-28. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1104&context=psychfacpub

Rosas, J., & McCall, R. B. (2009). Characteristics of institutions, interventions, and resident children’s development. (Unpublished manuscript). University of Pittsburgh Office of Child Development, Pittsburgh, PA.

Schore, A. N. (2001). Effects of a secure attachment relationship on right brain development, affect regulation, and infant mental health. Infant Mental Health Journal, 22(1-2), 7-66.

Shabazian, A. N., & Lopez, M. E. (2011). Best practices in early childhood care in limited resource institutions. Managua, Nicaragua: Whole Child International.

Smyke, A.T., Koga, S.F., Johnson, D.E., Fox, N.A., Marshall, P.J., Nelson, C.A., Zeanah, C.H., & the BEIP Core Group (2007). The caregiving context in institution-reared and family-reared infants and toddlers in Romania. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48(2), 210-218. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01694.x

Social Development Division and the Statistics and Economic Projections Division of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. (2012). Social panorama of Latin America. Santiago, Chile: United Nations Publications.

Sparling, J., Dragomir, C., Ramey, S. L., & Florescu, L. (2005). An educational intervention improves developmental progress of young children in a Romanian orphanage. Infant Mental Health Journal, 26(2), 127-142.

The St. Petersburg-USA Orphanage Research Team (2005). Characteristics of children, caregivers, and orphanages for young children in St. Petersburg, Russian Federation. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology: Special Issue on Child Abandonment, 26(5), 477-506

Vorria, P., Papaligoura, Z., Dunn, J., Van IJzendoorn, M. H., Steele, H., Kontopoulou, A., & Sarifidou, A. (2003). Early experiences and attachment relationships of Greek infants doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2005.06.002

Tobis, D. (2000). Moving from residential institutions to community based social services in Central and Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. Washington, DC: World Bank

United Nations Children’s Fund. (2009). Progress for children: A report card on child protection. Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/protection/files/Progress_for_Children-No.8_ EN_081309%281%29.pdf

Whitaker, R. C., Orzol, S. M., & Kahn, R. S. (2006). Maternal mental health, substance use, and domestic violence in the year after delivery and subsequent behavior problems in children at age 3 years. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(5), 551-560. doi:10.1001 /archpsyc.63.5.551

Orphanage Improvement: An Important Part of the Child Protection Discussion

Authors

Lopez, Meghan E.,

Whole Child International,

Shabazian, Ani N.,

Loyola Marymount University,

Spencer, Karen A.,

Whole Child International,

Nicaragua