After reading this new issue of WAIMH Perspectives, with the description of the work reported in Guatemala, South Africa, and New Zealand, as well reference to the previously published document from Australia, Infants in Immigration Detention, I became convinced of the need to add the anthropological dimension to our clinical work. This is necessary if we want to understand and help populations, many vulnerable and disadvantaged, in their own communities, as well as refugees from warn-torn countries who have experienced traumatic losses, including the loss of their homes, belongings and places of work. Not by chance, this issue of Perspectives comes out at a time when the magnitude of the “European refugees’ problem” reveals itself as a huge challenge, not only for politicians, but also for mental health professionals.

Let’s imagine that you receive referrals of infants and young children – refugees – who have recently arrived in your country. Their families have fled their own war-torn country, a place that is very different from your own. You have worries about developmental delays in multiple domains, relational disturbances and significant signs of trauma and distress. Where will you begin? How will you determine the needs and strengths of the infants referred? How will you best help refugee families to cope?

On the other hand, you may travel far away to study early child development as Peter Rohloff and his colleagues describe in a very interesting paper, Field Report: Early Child Development in Rural Guatemala (LINK). Or, your work may be in your home country, as Kerry Anne Brown, Carla Brown, and Astrid Berg describe in their paper, A Parent Group Initiative in an Intensive Care Unit in South Africa (LINK), about practices in a pediatric hospital in South Africa.

Confronted by cultures where young children and their families face tremendous health, relational, and cognitive difficulties, you may be challenged to understand and deliver services that are respectful of unique customs or beliefs.

Clinicians who are oriented toward Western culture and values might find their tools of assessment and treatment approaches inadequate when responding to infants and families whose cultural beliefs and attitudes towards life’s adversities are different from their own. Ethno-psychiatry has existed as a field for years, but has been quite marginal. It may become a flourishing domain.

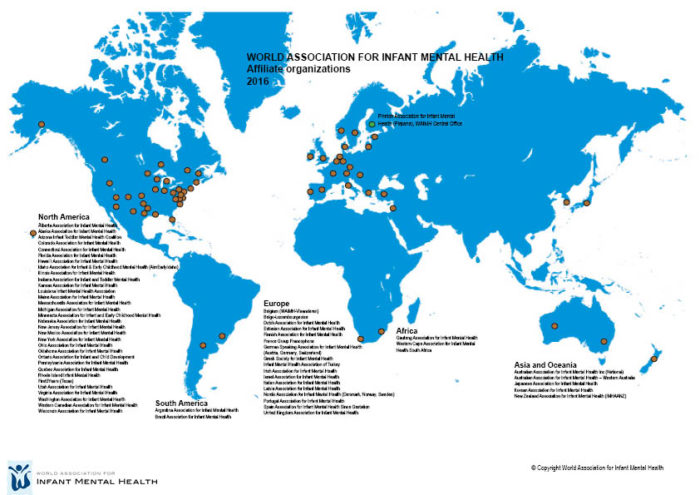

WAIMH, as a world association, is an organization where professionals from different disciplines and cultures bring their own views and clinical understanding. Still, tools of evaluation and therapeutic approaches primarily reflect Western practices and beliefs. In situations of war and humanitarian catastrophes, some may open their practices to very young children and families who have suffered displacement and are seeking help, far away from their native homes, and some may go to other countries to help children and families in need. For all, knowledge about each individual’s culture will be as important as knowledge in crisis intervention or treatment techniques. Just as the general practitioner needs to take advice from the expert in cardiology, we may each need to take advice from anthropologists or have them as members of our multidisciplinary teams!

We will have a chance to discuss these important issues in Prague this year when you come to the 15th WAIMH Congress Infant Mental Health in a Rapidly Changing World: Conflict, Adversity, and Resilience (LINK). Indeed, in light of our theme and recent events around the world, we have planned a Pre-Congress Symposium on WAIMH policy in times of peace and of humanitarian catastrophes.

Also related to the issues of policy, we include the WAIMH Position Paper on the Rights of Infants (LINK). The version that was presented in Edinburgh in 2014 (at the WAIMH Congress Presidential Symposium) has been amended in response to members’ comments and refined by WAIMH Board Members. Its present version is published in this issue of Perspectives. In addition, the WAIMH office will send a copy of the paper to each Affiliate President. Our wish is that each Affiliate starts using it with its local health policy makers and gives us feedback. After one or two years, we will decide whether WAIMH should move the policy document from a Position Paper to a Declaration (with its legal implications). As you will see, the infant’s right for culturally sensitive assessment and treatment is mentioned in the WAIMH paper.

Of additional importance, the assessment manual, Diagnostic Classification of Mental Health and Developmental Disorders of Infancy and Early Childhood, Revised (DC 0-3R), is under revision by the National Center for Infants, Toddlers and Families ZERO TO THREE in collaboration with WAIMH members. It will be presented during the WAIMH Pre-Congress day, with special attention given to the cultural aspects of diagnosing very young children.

Join us, meet, and discuss important clinical, policy, and research issues in Prague, the bridge between Eastern and Western Europe!

Warm regards to all of you.

Authors

Keren, Miri, MD,

WAIMH President,

Isreal