Summary

The negative consequences of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) on the physical and mental health of infants and young children has been well-established. In order to reduce the potential effects of these stressful events, inquiring about ACEs in pregnant women, infants, and young children has been identified as an important avenue for prevention. As such, there has been an impetus to use questionnaires asking about ACEs in both the prenatal and pediatric primary care settings. Although the assessment and identification of childhood adversity may be a first step in mitigating poor health outcomes associated with exposure to ACEs, concerns about the potential for discomfort in being asked to report ACEs, lack of trauma-informed training available to healthcare providers, low availability of resources for individuals with high ACEs, and feasibility of asking such questions, have been raised with regard to obtaining ACE histories in primary care settings. The overarching goal of this narrative review was to summarize the existing literature on ACEs history taking in the healthcare setting for pregnant women and children under the age of 6 years. The current review had three main research objectives: 1) to summarize research on parent perspectives on the use of an ACEs-related questionnaire in the prenatal and primary care setting, 2) to summarize research on the perspectives of healthcare providers using an ACEs related questionnaire with patients in pregnancy and under the age of 6, and 3) to identify gaps in the current literature and provide recommendations for future research.

Introduction

Over the last two decades, there has been a fundamental shift in the understanding of the origins of health and disease across the lifespan: adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) can initiate a cascade of events that may lead to negative consequences for an individual’s physical and mental health. Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) include stressful or traumatic events such as abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction, that occur before the age of 18. The initial ACE study found that exposure to adversity is common with 65% of adults having experienced at least one ACE in childhood and 12% of adults experiencing 4 or more ACEs. They also found a dose-response association between ACEs and health difficulties: as ACEs increase, so too does the consequential effect on health (Felitti et al., 1998).

Although the medical field was revolutionized by this conceptualization of determinants of health and disease in adulthood, research in the fields of infant mental health and developmental psychopathology have long demonstrated the detrimental effect of early adversity (Cicchetti & Toth, 2015; Rutter, 1977). Specifically, exposure to adversity in early childhood has been linked to alterations in the developing brain that have consequences across domains of cognitive, behavioural, social, and emotional functioning (Shonkoff et al., 2012). More recently, the intergenerational transmission of adversity has been demonstrated, whereby parents with high levels of childhood adversity are more likely to have children who also experience adversity (Madigan et al., 2019), as well as developmental difficulties, child mental health disorders, and poor physical health (Choi et al., 2017; Folger et al., 2018; Madigan, Wade, Plamondon, Maguire, & Jenkins, 2017; Racine, Plamondon, Madigan, McDonald, & Tough, 2018). This transmission is hypothesized to occur via biological embedding as well as through environment experiences and exposures (Buss et al., 2017; Racine, Plamondon, et al., 2018). Given that pregnancy and early childhood are sensitive periods for experiencing adversity and its intergenerational transmission, identifying ACEs during these periods has been highlighted as a potential step in preventing the cascade of developmental issues characterized by high ACE scores (Garner et al., 2012; Hudziak, 2018).

In response to this research evidence, prenatal and pediatric clinics across North America and abroad have started to implement routine ACE history-taking to identify both children and their parents who may be at risk of poor health outcomes. Despite the adoption of ACEs history taking as a preventative measure, concerns related to this widespread implementation exist, most notably in relation to potential distress or discomfort for families, the lack of evidence-based treatments specifically tailored for families with high ACE scores, and the availability of resources and trauma training (Finkelhor, 2018; McLennan et al., 2019). Furthermore, there remains a lack of consensus on what adverse experiences should be included as items within the questionnaire (Lacey & Minnis, 2019). Lastly, little is known about whether asking parents about their child’s ACEs as well as their own leads to any tangible benefits or adverse events such as distress and discomfort. A summary of the perspectives of parents and healthcare providers in studies that have implemented ACE history taking is needed to inform practice and future research directions.

To our knowledge, there is no overview of how ACEs questionnaires are used in the prenatal and pediatric setting, and how feasible and acceptable this practice is to families and care providers. Therefore, the purpose of this narrative review was to understand the implications of asking about ACEs within these primary care settings. The three main objectives that guided this review were as follows: 1) to summarize research on parent perspectives on the use of the ACEs questionnaire in the prenatal and primary care setting, 2) to summarize research on the perspectives of healthcare providers using the ACEs questionnaire with patients in pregnancy and under the age of 6, and 3) to identify gaps in the current literature and provide recommendations for future research. The synthesis of information surrounding ACE history taking will provide tangible recommendations to practitioners who use the ACEs questionnaire, and inform clinical practice guidelines related to identifying child and parent ACEs in primary care.

Methods

A narrative review, as defined by Bryman (2012), served as the methodological guiding tool for this review. A narrative review was selected as outcomes were not consistently reported across studies and could not be easily extracted or analysed through a meta-analysis. A systematic approach to the literature search was conducted to allow for a comprehensive search and to increase the validity of findings (Bryman, 2012; Haddaway, Woodcock, Macura, & Collins, 2015).

To identify relevant articles, searches were conducted in January-February 2019 in the databases MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and CINAHL with no restrictions or filters enabled in the search. The search strategy was developed in collaboration with a Health Sciences librarian and included a combination of MeSH headings and search terms. ACEs were searched as Adverse childhood* and combined with terms related to “healthcare setting” and “screening”. A cited reference search was also conducted of key articles that were previously identified.

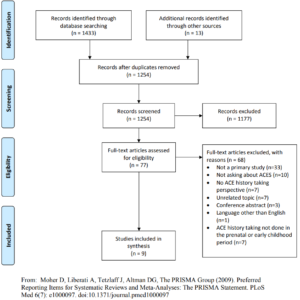

A total of 1,447 studies were initially identified, and primary studies were included if they: 1) asked parents about two or more categories of ACEs as defined by Felitti et al. (1998); and 2) reported on one of the following outcomes: provider outcomes, parent/child outcomes, and feasibility. Studies were excluded if they were conference abstracts and review articles, and if the topic was unrelated (i.e., not in a pediatric or prenatal setting). Furthermore, studies were only included if parents were asked about their own ACEs or the ACEs of a child who was under the age of 6. After abstract reviews and full-text article review of 77 studies, 9 articles were deemed to meet inclusion criteria for the narrative review (see Figure 1 for a detailed flow diagram of the review process).

Results

Study Characteristics

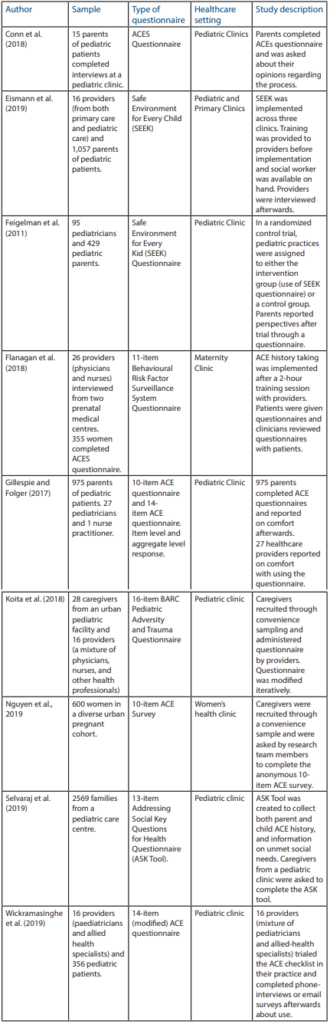

Of the 9 studies that met inclusion criteria, one study examined healthcare provider perspectives of ACE history taking, three studies provided parent perspectives, and the remaining 5 studies provided perspectives from both healthcare providers and parents. The majority of the studies provided outcomes on ACE history taking in pediatric care facilities (n=6), while the others provided perspectives in either a prenatal care setting (n=1), a primary care setting (n=1), or a mixture of both primary and pediatric care (n=1). With regards to the types of ACE history obtained, 4 studies obtained a parental report of their child’s ACEs, 3 studies obtained a report of parental ACEs only, and 2 studies obtained both child and parent ACEs. The majority of studies were conducted in the USA (n=8), while 1 was conducted in Australia. A description of the study characteristics can be found in Table 1.

Outcomes of obtaining an ACE history were identified from the included studies and were divided into two main categories: parent perspectives and healthcare provider perspectives. A summary of the results can be found in Table 2. Parent outcomes included parent comfort and perceived benefits of providing an ACE history. Healthcare provider outcomes included healthcare provider comfort, perceived benefits of history-taking practices, concerns, resource use and availability, and trauma-informed training. Healthcare providers also provided information on the feasibility of ACE history-taking such as the time required and the type of questionnaire used. Descriptive data were reported when provided by the study authors.

Parent Perspectives

Parent Comfort

Six studies provide information on parent comfort with being asked about their child’s ACEs or their own ACE history (Conn et al., 2018; Eismann, Theuerling, Maguire, Hente, & Shapiro, 2019; Feigelman, Dubowitz, Lane, Grube, & Kim, 2011; Flanagan et al., 2018; Koita et al., 2018; Nguyen et al., 2019; Selvaraj et al., 2019). One study reported that “only a small handful of caregivers” refused to complete the questionnaire or discuss results, although an exact percentage was not provided (Eismann et al., 2019), while another study reported that 5% of parents (35 out of 660) declined to complete the ACEs questionnaire when asked (Nguyen et al., 2019). Two other studies reported that the majority of patients (85-86%) wanted ACE history taking to continue (Flanagan et al., 2018; Selvaraj et al., 2019). In contrast, Koita et al. (2018) reported that 50% of parents who were asked about their children’s ACEs experienced discomfort, as items generated emotional responses of parents’ past experiences as children. However, patients still reported gratitude about being asked about adversity, and recognized the importance of being asked (Koita et al., 2018).

Of the four studies that asked about parental ACEs, there were mixed findings regarding parent comfort with reporting on their own ACEs (Conn et al., 2018; Flanagan et al., 2018; Gillespie & Folger, 2017; Selvaraj et al., 2019). Two studies found that parents were more comfortable reporting on their children’s ACEs than their own (Conn et al., 2018; Selvaraj et al., 2019). However, two other studies reported that the majority of parents (e.g., 62.6% in Gillespie & Folger, 2017) were comfortable with being asked about their own ACEs (Flanagan et al., 2018; Gillespie & Folger, 2017), were grateful to have been asked about adversity (Gillespie & Folger, 2017), and gave little resistance to providers (Gillespie & Folger, 2017). One study found that parent comfort with being asked about ACEs was moderated by patient ACE scores, with a greater majority of parents with low ACE scores (76.3%) reporting being comfortable with answering questions about ACEs, compared to parents with high ACE scores (34.9%) (Flanagan et al., 2018).

Although not a direct measure of parent comfort, one study reported that parent completion of ACE questionnaires differed by location within the facility, and timepoint when the ACEs history was obtained (Nguyen et al., 2019). The aforementioned study reported that 9.3% more parents completed ACEs questionnaires when asked in an examination room, in comparison to an outpatient waiting room. Furthermore, the study also reported that parents asked in the prenatal period may have been more comfortable answering questions regarding their ACE history in an outpatient setting, in comparison to parents in the postpartum period who were asked in an inpatient setting. Whether the time period or location impacted the comfort in reporting is unknown.

Perceived Benefits

Of the five studies that asked about parental ACEs, one study reported that obtaining an ACE history contributed to mothers feeling better understood by healthcare providers (Flanagan et al., 2018), and in another, improved satisfaction by parents was reported (Feigelman et al., 2011). Two studies reported that ACE history taking resulted in patients viewing their care provider as a resource (Conn et al., 2018; Selvaraj et al., 2019). Two studies also reported that patients recognized the importance of ACE history taking as it made them want to learn more about ACEs, resilience, and parenting (Conn et al., 2018; Gillespie & Folger, 2017).

Healthcare Provider Perspectives

Healthcare Provider Comfort

All four studies that reported on healthcare provider comfort asking about ACEs found that the majority of healthcare providers were comfortable asking about and discussing ACEs with patients (Eismann et al., 2019; Flanagan et al., 2018; Koita et al., 2018). One study reported that provider comfort increased with practice (Flanagan et al., 2018), while two others reported provider comfort increased with training (Eismann et al., 2019; Feigelman et al., 2011). Overall, the majority of healthcare providers were comfortable with asking about ACEs.

Perceived Benefits

Five studies reported on healthcare provider perceived benefits to ACE history taking (Eismann et al., 2019; Feigelman et al., 2011; Flanagan et al., 2018; Gillespie & Folger, 2017; Wickramasinghe, Raman, Garg, Jain, & Hurwitz, 2019). Providers found that asking about ACEs led to more understanding and trusting relationships with patients, and new conversations that allowed providers to support patients in new ways (Eismann et al., 2019; Gillespie & Folger, 2017). Providers saw patient ACEs history as valuable (Gillespie & Folger, 2017; Wickramasinghe et al., 2019) and wanted to continue the practice of asking about them (Feigelman et al., 2011; Flanagan et al., 2018; Wickramasinghe et al., 2019).

History-Taking Practices

Four studies reported on current history taking practices for asking parents about child ACEs (Eismann et al., 2019; Feigelman et al., 2011; Gillespie & Folger, 2017; Wickramasinghe et al., 2019). Three studies (Eismann et al., 2019; Gillespie & Folger, 2017; Koita et al., 2018) that undertook history taking with underprivileged populations asked about additional factors outside the original ACEs questionnaire such as food insecurity (Eismann et al., 2019) or neighbourhood violence (Eismann et al., 2019; Gillespie & Folger, 2017; Koita et al., 2018). One study reported high rates of ACE history taking (all 8 providers in the practice) because of the high instances of trauma in the population (Wickramasinghe et al., 2019). Overall, few providers asked about household dysfunction such as exposure to caregiver mental illness, caregiver substance use, or exposure to domestic violence, and providers were more likely to ask about ACEs if they worked with high-risk populations or had prior knowledge about the effect of ACEs on health.

Healthcare Provider Concerns

Four studies reported on healthcare provider concerns about ACE history taking (Eismann et al., 2019; Flanagan et al., 2018; Gillespie & Folger, 2017; Koita et al., 2018). Overall, the three major provider concerns about asking about ACEs were resource availability, lack of trauma training, and the increased time asking about ACEs would add to patient visits.

Three studies reported that providers were concerned that there were limited resources available to support patients with elevated ACEs (Eismann et al., 2019; Gillespie & Folger, 2017; Koita et al., 2018). Providers from Eismann et al. (2019) also reported being concerned about not knowing enough about resources in the community to assist caregivers. Providers from Flanagan et al. (2018) suggested that resources should be in place prior to implementing routinely asking about ACEs. Three studies identified a lack of knowledge on how to deal with trauma as a major concern, particularly with not knowing how to respond to patients with high ACE scores (Eismann et al., 2019; Flanagan et al., 2018; Gillespie & Folger, 2017). Gillespie and Folger (2017) reported that providers were particularly concerned about triggering an emotional response when asking about parental ACEs. Providers from Eismann et al. (2019) were concerned about offending parents when asking about their child’s exposure to parental mental health, substance abuse, or domestic violence.

Three studies reported concerns about the extra time asking about ACEs would add to patient visits (Eismann et al., 2019; Gillespie & Folger, 2017; Koita et al., 2018). Providers from Eismann et al. (2019) reported that they thought asking about ACEs was worth the extra time, but already had pre-existing time pressures to consider. Gillespie and Folger (2017) reported an initial concern about timing prior to when they started asking about ACEs, and this remained a concern in the post-study interview.

Resource Use and Availability

Five studies reported on resources available in the primary care setting. Four of these five studies reported that social workers or counselling services were available within the medical practices, which were either provided by the study authors or were existing beforehand (Eismann et al., 2019; Feigelman et al., 2011; Flanagan et al., 2018; Selvaraj et al., 2019). All four studies reported using their available resources when needed. One study that had social workers and community health workers on site reported that having these personnel onsite as resources was helpful (Eismann et al., 2019). Resources were not provided or available in one study as they were not reported to be needed (Gillespie & Folger, 2017). Overall, most practices had an integration of social services in preparation for ACE history taking and resources were typically used for children’s ACEs rather than parent ACEs.

Trauma-Informed Training

Three studies reported that providers received training before they started asking about ACEs (Eismann et al., 2019; Feigelman et al., 2011; Flanagan et al., 2018). Training ranged from 2-8 hours (mean=6 hours), and training procedures included an introduction to trauma-informed care, information on resources in the community, and the health effects of ACEs (Eismann et al., 2019; Feigelman et al., 2011; Flanagan et al., 2018). Two studies reported that training increased provider comfort with asking about ACEs and confidence in their ability to help patients (Eismann et al., 2019; Feigelman et al., 2011; Flanagan et al., 2018). One study found that after receiving training, physicians were more inclined to ask their patients about ACEs (Feigelman et al., 2011). In sum, more training was associated with higher comfort of healthcare providers and increased likelihood of asking about ACEs.

Timing

Three studies reported on the time it took to ask about ACEs (Eismann et al., 2019; Gillespie & Folger, 2017; Wickramasinghe et al., 2019). All studies used different tools to ask about ACEs, each with varied questions of varying lengths. For the two studies that asked about child ACEs, the 15-item Safe Environment for Every Child (SEEK) was used in one, and in the other the 14-item ACE questionnaire was used (Wickramasinghe et al., 2019). The third study asked about ACEs in parents, and used both the 10-item and the 14-item ACE questionnaire (Gillespie & Folger, 2017). However, all three studies found that asking about ACEs only added 1-5 minutes to the visit with each parent. One study that did not report timing did however report that interviews with high ACE patients were longer than interviews with low ACE patients (Flanagan et al., 2018). Providers from Eismann et al. (2019) reported that they thought the extra time added to the visit due to ACE interviews were worth it.

Questionnaire Type

Studies varied in the way they asked about ACEs. In addition to the 15-item SEEK questionnaire (Eismann et al., 2019), the 10-item ACE questionnaire (Gillespie & Folger, 2017) and the 14-item ACE questionnaire (Gillespie & Folger, 2017; Wickramasinghe et al., 2019), one study used the 11-item Behavioural Risk Factor Surveillance System Questionnaire (Flanagan et al., 2018) to screen for ACEs, and two studies (Koita et al., 2018; Selvaraj et al., 2019) created their own tool to identify ACEs by combining aspects from the original ACE questionnaire (Felitti et al., 1998) and other social factors. Furthermore, studies differed in the way they used their questionnaire. For instance, one study paired identified ACEs along with resilience factors, which providers found beneficial (Flanagan et al., 2018). Another study trialled both an item-level response questionnaire and an aggregate-level response questionnaire, and found that an aggregate-level response led to higher ACE identification (Gillespie & Folger, 2017).

Discussion

With the goal of mitigating the effect of ACEs on infant and maternal mental health and well-being there has been a rapid implementation of ACE history taking in prenatal and pediatric primary care settings. However, there are concerns that this practice may be premature due to the lack of evaluation of potential harms, the lack of targeted interventions for individuals with high ACEs, and challenges with regards to what ACE items should be asked about (Finkelhor, 2018; McLennan et al., 2019). Thus, we conducted a narrative review to summarize the existing literature on parent and healthcare provider perspectives on ACE history-taking within the primary care setting as well as identify implications for clinical practice and directions for future research. Three important findings emerged from the current review: 1) a large proportion of parents (up to 50%) experienced discomfort from being asked about ACEs, particularly parents with high ACEs, 2) trauma-informed training and adopting a trauma-informed approach is needed prior to implementing an ACE history-taking strategy within a clinic or organization (Racine, Killam, & Madigan, 2019), and 3) the availability of resources for patients and families who are asked about ACEs and need additional support is critical. Clinical implications of these findings for the practice of infant mental health as well as areas where more work and evidence are needed are discussed below.

Across the reviewed studies there was variability in the level of comfort parents experienced when reporting on ACEs in the primary care setting. While some parents reported feeling comfortable providing a report, other studies demonstrated that half of parents experienced discomfort when reporting on their family history of adversity (Koita et al., 2018). Furthermore, comfort for providing a report was influenced by the parent’s ACE score and the location the questionnaire was given, as parents generally felt more comfortable reporting on their child’s ACEs than their own, and were more likely to report their ACEs history in a private examination room in comparison to clinic waiting rooms. These findings suggest that healthcare providers should be mindful of the potential discomfort parents may experience when reporting on their histories of child adversity and use trauma-informed approaches that minimize re-traumatization (SAMHSA, 2014). For example, ensuring a safe and private clinic environment, as well as ensuring staff are aware of the wide impact of trauma are needed. There are also several strategies that could be used within primary care practice that could help reduce parent discomfort and distress. For example, using an aggregate-level ACEs score rather than asking about specific adversity experiences may help reduce discomfort and increase privacy (Gillespie & Folger, 2017). Finally, health organizations and clinics should consider whether asking about ACEs is appropriate in their setting and whether the information is needed or has the potential to improve the outcomes of infants and young children in their practice. For example, will obtaining this information change the approach to care or have the potential to improve outcomes? The potential benefits of ACEs history taking in clinical practice should be weighed against the potential harms, such as parent discomfort.

Healthcare providers identified that trauma-informed training was integral to knowing how to ask and respond when obtaining an ACE history. Across studies in the current review, healthcare providers varied in the training they received on ACEs, however, a consistent concern that was identified was how to respond to patients with high ACE scores. Training in trauma-informed approaches to patient-care was found to improve healthcare provider comfort in asking about ACE. Thus, trauma-informed training should be required by all staff to successfully meet the needs of complex families. Components of a trauma-informed training program should provide information on the impacts of ACEs on health, instructions on how to sensitively respond to individuals who have experienced trauma, and guidance on how to use and incorporate community resources (SAMHSA, 2014). Future research is needed to evaluate how using trauma-informed training approaches may be associated with parent-child health outcomes.

A third important finding identified by the current review is the importance of having resources available for patients to access if they are identified as needing support following an ACE history taking. Studies in our review demonstrated that the presence of mental health personnel, such as social workers, was not only feasible but also already present in several studies. Healthcare providers generally reported that these additional resources were helpful for addressing ACEs. Pediatricians interviewed in a study conducted by Bright, Thompson, Esernio-Jenssen, Alford, and Shenkman (2015) suggested that the use of a multidisciplinary team integrated with community supports such as social workers, teachers, and psychologists was beneficial when asking about past histories of trauma. For organizations where these resources are not readily available, the development of community partnerships can help to fill these service gaps and connect families with the resources they need such as treatment programs, food vouchers, and housing aid (Hall, Porter, Longhi, Becker-Green, & Dreyfus, 2012; Jichlinski, 2017; Plax, Donnelly, Federico, Brock, & Kaczorowski, 2016). Future research needs to identify which resources are beneficial for families with high ACE scores as well as guidance for healthcare professionals on how to acquire and develop community partnerships to meet their patients’ needs.

There remain several important future directions to consider with regards to ACE-history taking. First, there was no standardized measure for obtaining an ACEs history across studies. As can be seen in the current review, studies used different questionnaires of different lengths, resulting in a variation in the length of time added to the interview, and the items asked. Currently, there remains no consensus on which adverse childhood experiences are most important to ask about in primary care (Finkelhor, 2018; McLennan et al., 2019). While all studies in this review generally asked about abuse, neglect, or household dysfunction as specified by the original ACE study (Felitti et al., 1998), some studies also asked about factors outside the scope of ACEs such as food insecurity (Eismann et al., 2019; Koita et al., 2018), neighbourhood violence (Eismann et al., 2019; Gillespie & Folger, 2017; Koita et al., 2018), or refugee trauma (Wickramasinghe et al., 2019). These factors have been argued to produce similar effects on long-term health, which suggest that a rigorous evaluation of which childhood adversities should be asked about is needed (Finkelhor, 2018; Finkelhor, Shattuck, Turner, & Hamby, 2013; Lee, Larkin, & Esaki, 2017; Purewal et al., 2016). Indeed, the types of questions that are relevant may vary and differ across clinical populations. However, as noted by Lacey and Minnis (2019), there remains a lack of evidence-based justification as to why even the original 10 ACEs ought to be included in an ACEs questionnaire, let alone other adversities as well. Thus, future research should identify which ACEs are most pertinent to infant mental health outcomes, and how they can be applied across a variety of populations.

A second, future direction is to identify the potential benefits of considering past and current resilience factors that may be present in the lives of infants and young children. One study found that the use of a resilience questionnaire in pregnancy in addition to asking about adversity was beneficial (Flanagan et al., 2018) as identification of resilience factors helped providers better understand patients current coping abilities and availability of support resources. Furthermore, research has demonstrated that resilience factors, such as social support, can attenuate the association between ACEs and relationship difficulties (Madigan, Wade, Plamondon, & Jenkins, 2016), as well as ACEs and difficulties in pregnancy (Narayan, Rivera, Bernstein, Harris, & Lieberman, 2018; Racine, Madigan, et al., 2018). For instance, Madigan et al. (2016) found that the associations between ACEs and marital conflict in the postnatal period was moderated by neighborhood social support: higher ACEs was not associated with marital conflict when neighborhood social support was identified as being high. In addition, a study conducted by Narayan et al. (2018) found that the identification of resilience factors, or benevolent childhood experiences, accounted for the reduced impact of high ACE scores on prenatal health. Thus, social support can act as an important buffer of the effect of ACEs on maternal health and functioning. As such, an understanding of the supports and coping skills that are present for families may be important indicators of overall health and functioning.

A third future direction is to identify when it may be most appropriate to take an ACEs history. As one study reported, the prenatal period may be a more opportune time than the postpartum period as to prevent the likely influence of stress and postpartum hormones from influencing patient comfort with completing the questionnaires (Nguyen et al., 2019). Parents may also have a more well-established relationship with a provider seen routinely in pregnancy than with inpatient staff immediately following birth. Overall, more research is needed to determine appropriate developmental timing for ACEs history taking.

Clinical Implications

The studies included in the current review suggest that asking about ACEs as a preventative measure to improve maternal and infant mental health provides some benefits such as an increased communication and identification of trauma, as well as increased interest in the relationships between trauma and parenting. However, there are major cautions to obtaining an ACE history in the healthcare setting as limited research is available on adverse events related to asking about ACEs. Although parents across studies included in the current review reported varying levels of discomfort with completing the questionnaire, no research to date has identified the extent to which the practice of asking about ACEs in primary care may lead to re-traumatization, particularly for individuals with substantial trauma histories, and how to mitigate these negative outcomes. Research is needed to identify both short and long-term adverse outcomes of asking about ACEs. Furthermore, a randomized control trial conducted by MacMillan et al. (2009) found that asking about interpersonal violence had little impact in reducing rates of interpersonal violence. As such in the context of ACEs, consideration as to whether the benefits of asking about ACEs is worth the risk of parent discomfort, or whether universal implementation of trauma-informed approaches (e.g., fostering trust, transparency, and empathy with families) may be sufficient, is critical. For organizations wishing to implement ACEs history-taking practices, it is important to ensure adequate resources to support caregivers and young children with high ACE scores are available. These resources may include partnerships with social services within the community such as but not limited to, counseling services or housing aid services. Having additional personnel on staff such as social workers may aid in the creation of these partnerships. Lastly, as one of the major concerns reported by providers was how they should deal with patients who’ve experienced trauma, healthcare providers considering adopting ACE-taking practices should ensure adequate trauma training is obtained prior to implementation.

Limitations

There are limitations to the current narrative review. The summaries generated in the current review were limited by the available evidence. Specifically, few studies reported on adverse outcomes related to ACE-history taking. This could be due to multiple reasons, such as publication bias, the low ACE prevalence across study samples, as well as the failure to collect data on adverse outcomes. For instance, most studies asked participants whether they were comfortable with being asked about ACEs, but not if patients experienced any discomfort or distress related to being asked. Future research should identify potential adverse outcomes of asking about ACEs in order to more accurately inform whether its implementation is appropriate. Another limitation of this review is that different questionnaires that asked about ACEs were used across studies. Therefore, comfort and other outcomes cannot be directly compared as they would be influenced by the type and format of the questionnaire (i.e. wording of questions), as well as the population being asked about ACEs. Research in this area would benefit from the development and use of an evidence-based standardized questionnaire. Furthermore, another limitation is because of the nature of the literature, our results were limited to the data that was available. Many studies reported the results in terms of “majority” and “minority”, which limited the specificity of our results.

Conclusions

While the results of this narrative review suggest that there are some benefits to asking about ACEs in the prenatal and pediatric primary care settings, such as parents feeling more understood by health care providers and healthcare provider perceptions of improved relationships with families, these benefits were contingent on trauma-informed training and the availability of resources and interventions for families. There remains a large need to evaluate whether asking about ACEs in the primary context improves patient outcomes. Organizations or practitioners who are considering implementing a system to identify the trauma experiences of the young children and parents they work with should consider whether specifically asking families about these experiences is necessary and whether other trauma-informed approaches, such as universal training for staff and the availability for resources for families presenting with difficulty, would be sufficient (Racine et al., 2019). The implementation and inclusion of an ACEs questionnaire in primary care should be carefully considered in the context of both the potential benefits and limitations.

References

Bright, M. A., Thompson, L., Esernio-Jenssen, D., Alford, S., & Shenkman, E. (2015). Primary Care Pediatricians’ Perceived Prevalence and Surveillance of Adverse Childhood Experiences in Low-Income Children. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 26(3), 686-700. doi:10.1353/hpu.2015.0080

Bryman, A. (2012). Social Research Methods (4th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Buss, C., Entringer, S., Moog, N. K., Toepfer, P., Fair, D. A., Simhan, H. N., . . . Wadhwa, P. D. (2017). Intergenerational Transmission of Maternal Childhood Maltreatment Exposure: Implications for Fetal Brain Development. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 56(5), 373-382. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2017.03.001

Choi, K. W., Sikkema, K. J., Vythilingum, B., Geerts, L., Faure, S. C., Watt, M. H., . . . Stein, D. J. (2017). Maternal childhood trauma, postpartum depression, and infant outcomes: Avoidant affective processing as a potential mechanism. Journal of Affective Disorders, 211, 107-115. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2017.01.004

Cicchetti, D., & Toth, S. L. (2015). Multilevel developmental perspectives on child maltreatment. Development and Psychopathology, 27(4 Pt 2), 1385-1386. doi:10.1017/S0954579415000814

Conn, A. M., Szilagyi, M. A., Jee, S. H., Manly, J. T., Briggs, R., & Szilagyi, P. G. (2018). Parental perspectives of screening for adverse childhood experiences in pediatric primary care. Families, Systems & Health, 36(1), 62-72. doi:10.1037/fsh0000311

Eismann, E. A., Theuerling, J., Maguire, S., Hente, E. A., & Shapiro, R. A. (2019). Integration of the Safe Environment for Every Kid (SEEK) Model Across Primary Care Settings. Clinical Pediatrics, 58(2), 166-176. doi:10.1177/0009922818809481

Feigelman, S., Dubowitz, H., Lane, W., Grube, L., & Kim, J. (2011). Training pediatric residents in a primary care clinic to help address psychosocial problems and prevent child maltreatment. Academic Pediatrics, 11(6), 474-480. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2011.07.005

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., . . . Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245-258. doi:10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8

Finkelhor, D. (2018). Screening for adverse childhood experiences (ACEs): Cautions and suggestions. Child Abuse & Neglect, 85, 174-179. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.07.016

Finkelhor, D., Shattuck, A., Turner, H., & Hamby, S. (2013). Improving the adverse childhood experiences study scale. JAMA Pediatrics, 167(1), 70-75. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.420

Flanagan, T., Alabaster, A., McCaw, B., Stoller, N., Watson, C., & Young-Wolff, K. C. (2018). Feasibility and Acceptability of Screening for Adverse Childhood Experiences in Prenatal Care. Journal of Womens Health, 27(7), 903-911. doi:10.1089/jwh.2017.6649

Folger, A. T., Eismann, E. A., Stephenson, N. B., Shapiro, R. A., Macaluso, M., Brownrigg, M. E., & Gillespie, R. J. (2018). Parental Adverse Childhood Experiences and Offspring Development at 2 Years of Age. Pediatrics, 141(4). doi:ARTN e2017282610.1542/peds.2017-2826

Garner, A. S., Shonkoff, J. P., Siegel, B. S., Dobbins, M. I., Earls, M. F., Garner, A. S., . . . Pediat, S. D. B. (2012). Early Childhood Adversity, Toxic Stress, and the Role of the Pediatrician: Translating Developmental Science Into Lifelong Health. Pediatrics, 129(1), E224-E231. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-2662

Gillespie, R. J., & Folger, A. T. (2017). Feasibility of Assessing Parental ACEs in Pediatric Primary Care: Implications for Practice-Based Implementation. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 10(3), 249-256. doi:10.1007/s40653-017-0138-z

Haddaway, N. R., Woodcock, P., Macura, B., & Collins, A. (2015). Making literature reviews more reliable through application of lessons from systematic reviews. Conservation Biology, 29(6), 1596-1605. doi:10.1111/cobi.12541

Hall, J., Porter, L., Longhi, D., Becker-Green, J., & Dreyfus, S. (2012). Reducing adverse childhood experiences (ACE) by building community capacity: a summary of Washington Family Policy Council research findings. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 40(4), 325-334. doi:10.1080/10852352.2012.707463

Hudziak, J. J. (2018). ACEs and Pregnancy: Time to Support All Expectant Mothers. Pediatrics, 141(4). doi:10.1542/peds.2018-0232

Jichlinski, A. (2017). Defang ACEs: End Toxic Stress by Developing Resilience Through Physician-Community Partnerships. Pediatrics, 140(6). doi:10.1542/peds.2017-2869

Koita, K., Long, D., Hessler, D., Benson, M., Daley, K., Bucci, M., . . . Burke Harris, N. (2018). Development and implementation of a pediatric adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and other determinants of health questionnaire in the pediatric medical home: A pilot study. PLoS One, 13(12), e0208088. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0208088

Lacey, R. E., & Minnis, H. (2019). Practitioner Review: Twenty years of research with adverse childhood experience scores – Advantages, disadvantages and applications to practice. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. doi:10.1111/jcpp.13135

Lee, E., Larkin, H., & Esaki, N. (2017). Exposure to Community Violence as a New Adverse Childhood Experience Category: Promising Results and Future Considerations. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 98(1), 69-78. doi:10.1606/1044-3894.2017.10

MacMillan, H. L., Wathen, C. N., Jamieson, E., Boyle, M. H., Shannon, H. S., Ford-Gilboe, M., . . . McMaster Violence Against Women Research Group, f. t. (2009). Screening for Intimate Partner Violence in Health Care Settings: A Randomized Trial. JAMA, 302(5), 493-501. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1089

Madigan, S., Cyr, C., Eirich, R., Fearon, R. M. P., Ly, A., Rash, C., . . . Alink, L. R. A. (2019). Testing the cycle of maltreatment hypothesis: Meta-analytic evidence of the intergenerational transmission of child maltreatment. Development and Psychopathology, 31(1), 23-51. doi:10.1017/S0954579418001700

Madigan, S., Wade, M., Plamondon, A., & Jenkins, J. M. (2016). Neighborhood Collective Efficacy Moderates the Association between Maternal Adverse Childhood Experiences and Marital Conflict. American Journal of Community Psychology, 57(3-4), 437-447. doi:10.1002/ajcp.12053

Madigan, S., Wade, M., Plamondon, A., Maguire, J. L., & Jenkins, J. M. (2017). Maternal Adverse Childhood Experience and Infant Health: Biomedical and Psychosocial Risks as Intermediary Mechanisms. Journal of Pediatrics, 187, 282-+. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.04.052

McLennan, J. D., MacMillan, H. L., Afifi, T. O., McTavish, J., Gonzalez, A., & Waddell, C. (2019). Routine ACEs screening is NOT recommended. Paediatrics & Child Health. doi:10.1093/pch/pxz042

Narayan, A. J., Rivera, L. M., Bernstein, R. E., Harris, W. W., & Lieberman, A. F. (2018). Positive childhood experiences predict less psychopathology and stress in pregnant women with childhood adversity: A pilot study of the benevolent childhood experiences (BCEs) scale. Child Abuse & Neglect, 78, 19-30. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.09.022

Nguyen, M. W., Heberlein, E., Covington-Kolb, S., Gerstner, A. M., Gaspard, A., & Eichelberger, K. Y. (2019). Assessing Adverse Childhood Experiences during Pregnancy: Evidence toward a Best Practice. American Journal of Perinatology Reports, 9(1), e54-e59. doi:10.1055/s-0039-1683407

Plax, K., Donnelly, J., Federico, S. G., Brock, L., & Kaczorowski, J. M. (2016). An Essential Role for Pediatricians: Becoming Child Poverty Change Agents for a Lifetime. Academic Pediatrics, 16(3 Suppl), S147-154. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2016.01.009

Purewal, S. K., Bucci, M., Gutiérrez Wang, L., Koita, K., Silvério Marques, S., Oh, D., & Burke Harris, N. (2016). Screening for adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) in an integrated pediatric care model. Zero to Three, 37(1), 10-17.

Racine, N., Killam, T., & Madigan, S. (In press). Trauma-informed care as a universal precaution: Beyond the Adverse Childhood Experiences questionnaire. JAMA Pediatrics.

Racine, N., Madigan, S., Plamondon, A., Hetherington, E., McDonald, S., & Tough, S. (2018). Maternal adverse childhood experiences and antepartum risks: the moderating role of social support. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 21(6), 663-670. doi:10.1007/s00737-018-0826-1

Racine, N., Plamondon, A., Madigan, S., McDonald, S., & Tough, S. (2018). Maternal Adverse Childhood Experiences and Infant Development. Pediatrics, 141(4). doi:10.1542/peds.2017-2495

Rutter, M. (1977). Family, area and school influences in the genesis of conduct disorders In L. Hersov, M. Berger, & D. Shaffer (Eds.), Aggression and Antisocial Behavior in Childhood and Adolescence (pp. 95-113). Oxford, England: Pergamon Press.

SAMHSA. (2014). SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. Retrieved from Rockville, MD:

Selvaraj, K., Ruiz, M. J., Aschkenasy, J., Chang, J. D., Heard, A., Minier, M., . . . Bayldon, B. W. (2019). Screening for Toxic Stress Risk Factors at Well-Child Visits: The Addressing Social Key Questions for Health Study. Journal of Pediatrics, 205, 244-+. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.09.004

Shonkoff, J. P., Garner, A. S., Siegel, B. S., Dobbins, M. I., Earls, M. F., Garner, A. S., . . . Wood, D. L. (2012). The Lifelong Effects of Early Childhood Adversity and Toxic Stress. Pediatrics, 129(1), e232. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-2663

Wickramasinghe, Y., Raman, S., Garg, P., Jain, K., & Hurwitz, R. (2019). The adverse childhood experiences checklist: Can it serve as a clinical and quality indicator? Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 0(0). doi:10.1111/jpc.14368

Funding

Research support was provided to Dr. Madigan by the Alberta Children’s Hospital Foundation and the Canada Research Chairs program. Dr. Racine was supported by a Postdoctoral Trainee Award from the Alberta Children’s Hospital Research Institute (ACHRI), the Cumming School of Medicine, and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

Authors

Whitney Ereyi-Osas, Nicole Racine PhD, Sheri Madigan PhD

Department of Psychology, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada

Alberta Children’s Hospital Research Institute, Calgary, AB, Canada

Address correspondence to: Sheri Madigan, Department of Psychology, University of Calgary, 2500 University Ave., Calgary, AB, T2N 1N4, Canada, Phone: (403) 220-5561; Fax: (403) 282-8249; email: sheri.madigan@ucalgary.ca