Introduction

In childcare settings, there are frequently struggles to balance affordable rates for parents, adequate salaries for providers, equitable resource allocation, and quality service implementation. Parents often face dilemmas balancing work responsibilities and personal goals with family responsibilities and sensitively meeting the needs of their children. With multiple financial and regulatory factors affecting provision of services, needs of young children may be compromised when management decisions are made. Kai von Klitzing provides a personal reflection that details historical factors in Germany that have resulted in inequities in staffing ratios in childcare settings. Similar challenges exist worldwide, with children caught in the middle. Barriers to accessing high quality care may pose difficult decisions with limited options for families. Providers may find themselves stretched thin when the number of children in their care is too high and insufficient resources are available. Babies and toddlers do not have a voice in these adult decisions, and their emotional needs may be overlooked when cost-cutting measures result in less-than adequate ratios. When systems do not prioritize children’s needs, long-lasting developmental consequences may ensue. How can we, as champions of young children, advocate for systems change that prioritizes children, facilitates relationship development, and provides sensitive caregiving by wrapping a network of support around families?

Introduction by Jody Todd Manly, USA, Associate Editor

Recently, the German Bertelsmann Foundation published a study that investigated how many infants (aged 0–3) on average are looked after by one professional nursery teacher in German nurseries (Ländermonitoring Frühkindliche Bildungssysteme). This is a relevant topic for several reasons. The results show how much a wealthy western industrialized country invests in early childcare and whether there are regional differences between the Eastern (until 1990 German Democratic Republic/GDR) and Western (former Federal Republic of Germany/FRG) parts of our country. The two parts of Germany have quite different histories. In the former GDR infants mainly grew up in state nurseries and saw their working parents only in the evenings (in some nurseries they even stayed the whole week) and at the weekend. In contrast, in the FRG the ideal of early education was that children should stay with their mothers until age 3 and then enter preschool or kindergarten. These different concepts are still present in the minds of many parents today, although a certain convergence has taken place over the last 30 years. Socially and politically, the two parts of Germany have also developed differently. In the Western part there is greater prosperity compared to the Eastern part; there is more economic power, people earn more money and are wealthier. This causes many inhabitants of the Eastern part of the country to feel they have been short-changed or even neglected. There is still considerable migration from the East to the West, there is more xenophobia in the East, and the rightwing Populist Party is more successful there (latest polls 22%) compared to the West (12%). So I was curious about the Bertelsmann Foundation’s results: would the considerable social differences be reflected in the ways that infants are cared for in public nurseries?

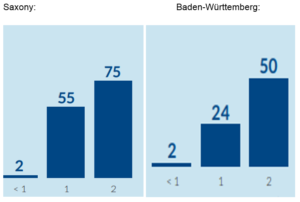

The results showed significant differences. In the largest East German state, Saxony, 2% of children aged < 12 months, 55% of children aged 1–2 years, and 75% of children aged 2–3 years spend more than 25 hours per week on average in a nursery. By comparison, in the West German state of Baden-Württemberg (BW) the numbers are significantly lower: 2% of children aged < 12 months, 24% of children aged 1–2 years, and 50% of children aged 2–3 years.

Furthermore, the majority of children in East Germany (Saxony 71%) spend more than 45 hours per week in the nursery whereas in West Germany (BW 50) only 24% spend more than 45 hours per week there. So quantitatively, in the Eastern part of Germany a large part of the care of infants aged 1–3 still takes places in institutions, whereas in the Western part of Germany mothers still provide most of the care.

Having this in mind I was surprised when I noticed the average staff member to child ratio: the Bertelsmann Foundation recommends a ratio of 1 professional nursery teacher to 3 infants aged 0–3. In the Western state (BW) the ratio currently is 1:3.2, whereas in the Eastern state (Saxony), the ratio is 1:7.5. That means that in the poorer Eastern region, more children aged 0–3 spend nearly twice as much time in nurseries compared to the richer Western region; at the same time, they receive less than half of the attention and care of their Western counterparts. Furthermore, the researchers drew our attention to the fact that there are always staff members who are not available because of illness, vacation or administrative work, so we may estimate that in the East German state on average one nursery teacher has to care for 8 to 9 children aged 0 to 3.

I must say I was really shocked by these results. Taking care of 8 infants at a time means being able to fulfil only their most basic needs like feeding and cleaning at the most. But there is no time to respond to their emotional needs for affection, attunement, consolation, regulation etc. That means that nationwide, a rich industrialized country like Germany does not provide sufficient care for the youngest members of the society, although it is a fact proven by many scientific studies that emotional neglect in the first three years creates a tremendous risk of later biological and psychiatric suffering over the whole life cycle. The foundations of moral, social, cooperative development have to be laid in the early years (See WAIMH’s 2017 position paper: The worldwide burden of infant mental and emotional disorder: report of the task force of the World Association for Infant Mental Health).

I was also shocked that the inequality of developmental opportunities between the two parts of our country seems to be deeply entrenched this early. After a few days I was even more shocked that the study, which had been reported in the newspapers, caused no public outcry at all. There is a lot of discussion in our media about the fact that adults in East Germany earn around 20% less than their colleagues in West Germany, and that old-age pensions are also lower. But the adult world does not notice that our very young children are at the mercy of this fundamental injustice and inequality!

I was already in a state of anger and sadness when a journalist from our local newspaper called and asked me, as the President of the World Association for Infant Mental Health, to comment on the results from the Bertelsmann Foundation. So, I put all my emotions into my response. The next day, an article appeared under the headline,

“Does Society Accept Child Maltreatment?”

Professor for Child Psychiatry Criticizes Persistent Inadequate Staffing Ratio in Eastern Nurseries“Kai von Klitzing, president of the World Association for Infant Mental Health, criticizes the dramatic shortage of nursery teachers in Saxon nurseries. ‘It looks as though society accepts childhood maltreatment.’ The professor for child psychiatry is surprised ‘that there is no real outcry about this unbelievable failure. Children in the eastern part of Germany seem to have only half the developmental opportunities of their counterparts in the western states.’ The medical doctor warns: ‘The lack of care can lead to emotional neglect in East German nurseries, which doubles the risk of biological as well as psychiatric illness over the life cycle. The lifelong feeling of having drawn the short straw, which is common in the eastern German states, is already being embedded during the first three years of life.’”

I must confess that these were provocative words. It was simply an attempt to summarize the state of scientific developmental knowledge and to open it up for public debate. It is clear that when one nursery teacher is responsible for 6 to 9 children aged 0 to 3 for several hours, most of the children may not receive adequate support or mirroring that could help them to regulate their own emotional states, to overcome their sadness at being separated from their parents, to manage their anxieties, and to fulfil their need to be loved and cared for. They may be well dressed, fed and clean, but it is possible that they will suffer emotional starvation for several hours every day. The younger they are the more this emotional neglect may overshadow their mood, their self-confidence, and their narcissistic homeostasis. Emotional neglect is probably the most common form of child maltreatment and one of the most important risk factors for many health problems, including cardiac, immunological and emotional diseases, as well substance abuse. Furthermore, early forms of neglect may have a negative effect on cooperative social and moral development, with enormous consequences for the society. For these reasons, I equate poor childcare with the strong words, emotional neglect and child maltreatment.

Three political parties are currently negotiating a coalition for the next government in our state. In addition to activities against climate change, the phasing out of brown coal mining, recruiting more police officers and teachers, improving the state nurseries is one of the hot topics. The politicians seem to agree that they must raise nursery teachers’ salaries and the quality of their education, and also significantly increase the staffing ratio. This makes me optimistic, because it shows that scientific efforts and advocacy for infants’ needs can lead to political change.

But I also received negative reactions to my statement in the local newspaper. One very good colleague of mine, a mother of 5 children and member of our local parliament, sent me the following email:

“I feel compelled to react to your statement published today in the newspaper. It is a shame that you used a term stemming from criminology in order to draw attention to a problem. And it is not objective or neutral to draw conclusions for the whole of society from a single (but important) issue. Furthermore, it is offensive to devalue the East Germans. Ultimately you attack women. I personally feel assaulted by your words. I protest against your reproach, that I emotionally neglected my children who all went to nurseries. I agree that the staffing ratio has to be improved. But the situation in the nurseries is the consequence and not the cause of the problems in our society.”

Immediately after I received this email, she called me and we had a very good conversation. She argued from a feminist point of view that the tradition in the former communist countries of providing nurseries for all infants from as early as possible enabled mothers to continue working even after they had children, and led to greater equality for women, a situation that was and is superior to the inequality of men and women in many Western countries.

The Swiss newspaper, Neue Zürcher Zeitung, recently entitled an article on the situation of parents in Germany: “On Callous Mothers (“Rabenmütter”) and Standout Fathers (“Spitzenväter”)” (30 Jahre Mauerfall: Was Gleichberechtigung ausmacht). The article went on to analyze the situation in Germany, where the women living in the Eastern parts defend their emancipated position against the traditional and old-fashioned role model in the Western parts of women who were ‘chained to house and home and economically dependent on their husbands.’ One of the reasons for the more progressive female position in the East is the fact that most children under 3 are cared for in a comprehensive network of nurseries. I think the author’s analysis was basically right, but in the whole article there is no mention of the situation of the young children.

The critique from my colleague affected me on a very personal level. We all try to raise our children in the best way possible within the circumstances in which we live. To do that we constantly have to make compromises. For example, if I raise my young child or children as a single parent, want to reach goals in my career or just have a job that provides a living for my family, I have no choice but to place my child or children in the nearest nursery that offers a place for day care. I hope of course that it is a good-quality nursery, but I see every day that there are not enough nursery teachers and that this places a burden on the teachers who are stressed and compromised in their ability to care for all the infants and young children in an age-appropriate way. I hope then that my child is resilient and can thrive in possibly less than optimal conditions. Sometimes I am also exhausted at the weekend and not as emotionally available for my child as I would like to be. All these limitations and inadequacies may provoke feelings of guilt in me, which is a heavy burden. But I have no choice: there are economic reasons why I cannot stay at home, and even if I could, I would not do it because I am also ambitious and do not want to give up my professional goals. So, when we express concern that our nurseries are shortstaffed and that infants do not receive the care that they need we are also criticizing ourselves for neglecting our own children by sending them to the available nurseries. So, our justified claim for quantitative and qualitative improvements in staffing in our nurseries may be accompanied by our own guilt feelings and doubts about our parental qualities.

There is a further dilemma: when we standup for infants’ rights to be raised within “sensitive and responsive caregiving relationships” (WAIMH Infant Rights Paper) and express our critique that these rights may not be guaranteed in under-resourced and under-staffed nurseries, we may be in conflict with women’s rights to participate equally in the social and professional life of our society. Of course this may imply the same problems for fathers, who feel responsible for their children. But in spite of the move towards a new fatherhood, most studies show that in our Western industrialized countries the vast majority of child-rearing work is still done by women. So, it is mostly women who are confronted with the dilemma between adequate care for their young children and maintaining their own professional careers and/or earning enough money for living. Therefore, as my colleague warned me, public critique of unsatisfactory conditions in nurseries can rapidly acquire a flavour of being reactionary and misogynist. (Incidentally, the same reproach can be made when we argue for the fundamental rights of unborn children).

The human rights attorney Bruce Adams argued at the Committee on the Rights of the Child Day of General Discussion, “Implementing Child Rights in Early Development”, on 17 September 2004 that many human rights are not absolute rights. For example, with respect to early childhood, there are two sets of interests: the mother’s well-being or autonomy, and the infant’s well-being. Like all basic rights, the right of the infant to grow up in the context of quantitatively sufficient, sensitive, and responsive caregiving relationships is also context-dependent and requires balancing decisions. This is what parents do in everyday life. On the one hand, they try to consider the needs of their young children, especially their need for a constant and affectionate parental figure; while on the other, they should not ignore their own wish to participate in adult life, their goals in their professional careers, and their economic situation, as well as their own need for adult intimacy. In the end, their parental practice is the result of compromise between these poles. If they completely lose sight of their children’s needs, they are neglectful parents.

To establish nurseries in which infants spend more or less time, are cared for by professional teachers and can have their first experiences with peers is a decision made by society in order to help parents and children to find compromises between the adults’ right to self-fulfilment, their economic needs and the infants’ right to reliable care. If a wealthy society and/or wealthy parents decide to resource these nurseries so that the staffing ratio makes it possible for nursery teachers to provide reliable care, with respect to each infant’s physical and emotional needs, we will have protected the rights of infants and very young children to the care they deserve in the early years.

To acknowledge the state principle of reasonable economic management and the goal of improving women’s rights to participation makes sense only if we also acknowledge the other side of the coin: the right of infants to grow up under suitable conditions. We can balance these poles, we can try to find compromises between different rights-holders in a society, but we cannot deny that our youngest members of the society, babies and infants, also have fundamental rights that must be seriously observed and respected.

Therefore, after all these reflections and considerations, I would conclude:

Yes, underfunding of nurseries in wealthy societies is a socially accepted form of child maltreatment!

Perspectives Editors reflective questions

The President of WAIMH, Professor Kai von Klitzing, has presented an historical context to understand the inequity of staffing ratios in early childhood care and education within Germany and foregrounds the infants’ experience of this inequity. Kai has raised these issues with courage and passion to give voice to infants’ experiences while also being compassionate, thoughtful, and acknowledging of the complex systems of care.

In so doing, his column calls us each, as WAIMH members and allied colleagues of WAIMH, to hold the infants’ experience in mind and to use this experience to find ways to voice what babies need in these circumstances. It also calls us connect with each other to further develop our professional sensitivity and responsiveness.

As such, we invite you to join with us and consider the following questions:

- What is needed within WAIMH so we can more fully acknowledge and support our early childhood education colleagues?;

- What is needed within WAIMH so we can continue to build a strong bridge between the health and education sectors?; and

- What useful global models and initiatives for early care and education from organisations such as UNICEF can we identify that lend support to our advocacy efforts with regard to this issue?

As editors we invite you to share your responses with us. We also especially invite early care and education colleagues and specialist consultants in the early care and education sector to be part of a special interest group to explore this issue on a global scale as a way to uphold the infants experience, be a voice for infants and their families, and to provide a WAIMH supported network for colleagues in this sector.

If you are interested in being part of this initiative, please contact the editors.

Authors

Kai von Klitzing, Germany