Abstract

Mothers who experienced adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and specific childhood maltreatment (CM) may exhibit specific risk for negative parenting behaviors; however, it is imperative to investigate potential mechanisms that may prevent the intergenerational transmission of such experiences. For example, ACEs/CM and negative parenting behaviors have been associated with mother-young child insecure attachment, but these variables rarely have been examined collectively. Thus, this study examined mother-young child insecure attachment patterns as mediators in the relationship between mothers’ ACEs/CM and negative parenting behaviors in a sample of 146 mothers with young children who ranged in age from 1½- to 5-years. Results indicated that mother-young child avoidant, anxious, and disorganized attachment patterns mediated significantly and fully the relationship between mothers’ ACEs and negative parenting behaviors and between mothers’ CM experiences and negative parenting behaviors. These findings suggested the need for trauma-informed parenting interventions with ports of entry that could support facilitation of mother-young child secure emotional connections and decrease the risk for maltreatment potential in mothers with histories of ACEs/CM themselves.

Decades of literature have described an intergenerational model for the ongoing cycle of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), or experiences of childhood maltreatment (CM; i.e., abuse and neglect) and household dysfunction, that can occur in families. Unfortunately, little is known regarding why such intergenerational cycles continually repeat. Formative in providing an empirical estimate of these intergenerational cycles, Kaufman and Zigler (1987) suggested that approximately one-third of individuals who experienced CM maltreated their own children. More recently, parents who reported CM were found to be more than two times as likely to have children who also experienced CM (Madigan et al., 2019). As may be expected, those parents who endorsed more chronic and frequent CM or multiple types of CM were even more likely to display abusive behaviors towards their own children (Jaffee et al., 2013; Pears & Capaldi, 2001). For example, higher rates of CM in parents were related to greater instances of physical punishment, child neglect, sexual abuse, and reports to Child Protective Services (CPS) in the children of these parents (Banyard, Williams, & Siegel, 2003; Widom, Czaja, & DuMont, 2015). A meta-analysis of 47 studies found wide-ranging support for this intergenerational cycle of CM, albeit with small to medium effect sizes (Thornberry, Knight, & Lovegrove, 2012). Certainly, although mothers with CM histories may exhibit a heightened risk for negative parenting behaviors (Lang, Garstein, Rodgers, & Lebeck, 2010), not every mother who experienced CM will go on to maltreat her own children (Madigan et al., 2019; Pears & Capaldi, 2001). Rather, mediating factors in the relationship between mothers’ ACEs/CM and their parenting behaviors with young children should be examined to help further the understanding of how these intergenerational cycles may occur (Thornberry et al., 2012).

Fundamental to the discussion of ACEs and CM experiences is the consideration that 91% of children are reportedly perpetrated against by a parental figure (USDHHS, 2018). As the very nature of caregiving necessitates providing safety for children, this paradox has striking implications for parent-young child attachment. The negative relationship between ACEs, CM experiences, and attachment was supported by a meta-analysis of 55 studies, with findings suggesting that children with CM experiences displayed significantly fewer secure attachment behaviors and significantly greater insecure or disorganized attachment patterns with their primary caregivers (relative to children without CM experiences; Cyr, Euser, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & van IJzendoorn, 2010). Overall, CM was associated with future difficulties in forming secure attachments when mothers had their own children (Berthelot et al., 2015; Iyengar, Kim, Martinez, Fonagy, & Strathearn, 2014).

According to Bowlby’s (1969) seminal attachment theory, the internal working models formed during early childhood are determined largely by reciprocal interactions with primary caregivers and are displayed consistently across generations. Thus, it can be inferred that a mother’s insecure attachment to her own childhood caregiver (i.e., the ‘ghosts in the nursery’, as described by Fraiberg Adelson, & Shapiro, 1975) may impact that mother’s ability to facilitate secure attachment with her own young children (Iyengar et al., 2014). Bolstering the notion of the intergenerational cycle of attachment (van IJzendoorn & BakermansKranenburg, 2019), young children of mothers who themselves had experienced CM had a greater likelihood of being classified as insecurely attached on the Strange Situation (Berthelot et al., 2015). Thus, there likely is a complex relationship between ACEs, CM experiences, and attachment.

In turn, quality of attachment has been related closely to parenting behaviors. Dykas and Cassidy (2011) posited that, in parent-young child dyads where the child is attached insecurely, parents likely process attachment information in a negative fashion, thereby contributing to poor parenting behaviors and reinforcing insecure attachment. Further, motheryoung child insecure attachment predicted significantly greater contacts received by mothers from CPS (Spieker, Bensley, McMahon, Fung, & Ossiander, 1996). In contrast, mothers with young children who were attached securely in the Strange Situation were observed to use more questioning techniques, were less intrusive, and were less likely to change the direction of their young child’s behavior during structured and unstructured tasks (Booth, Rose-Krasner, & Rubin, 1991). Moreover, mothers who understood and acted on their young children’s emotions exercised more adaptive parenting behaviors that increased mother-young child security, whereas mothers who exhibited low reflective ability with regard to their young children’s emotions experienced increased risk for insecure attachment and problematic parenting behaviors (Fonagy, Steele, & Steele, 1991).

In their comprehensive review of attachment and parenting behaviors, Jones, Cassidy, and Shaver (2015) concluded that parents’ own attachment insecurity was related consistently to negative parenting behaviors. Mothers with CM histories (and who widely had insecure attachment histories) exhibited lower quality of interactions with their infants and decreased ability to soothe their infants’ distress (Lang et al., 2010). A recent study suggested that, in mothers who had experienced CM, their dismissing and unresolved states of mind (originating from their attachment to their primary caregivers) were linked to insensitive parenting with their own children (Zajac, Raby, & Dozier, 2019). Although these data lend support for the link between mothers’ ACEs and CM experiences, attachment to their childhood caregivers, and negative parenting behaviors (Zajac et al., 2019), research has yet to examine the relationship between mothers’ ACEs and negative parenting behaviors with insecure attachment patterns to their own young children as mediators.

Given the aforementioned findings, mother-young child attachment patterns may serve as an important mechanism for explaining the connection between mothers’ ACEs and CM experiences and negative parenting behaviors (Jones, Cassidy, & Shaver, 2015). As a result, the current study aimed to investigate the predictive relationships among mothers’ ACEs and CM experiences, negative parenting behaviors, and patterns of mother-young child insecure (i.e., anxious, avoidant, disorganized) attachment, with mother-young child insecure attachment patterns acting as mediators in these relationships.

Method

Participants

An American community sample of mothers was recruited for participation through Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk), an online crowd sourcing marketplace. Initially, 1090 individuals attempted participation. Participants were disqualified for failure to meet eligibility criteria, multiple attempts to complete the survey, and incorrect answers on validity questions. Eligibility for participation included being at least 18-years of age, having a young child who was 1½- to 5-years of age, and residing in the United States. A sample of 146 mothers was included in final analyses. Mothers ranged in age from 21- to 52-years (M age = 32.08-years; SD = 6.16-years), with their young children ranging in age from 1½- to 5-years (M age = 3.10-years; SD = 1.11-years). Approximately 56% of these young children were female. The majority of mothers identified themselves as being White or Caucasian (i.e., 76.7%). This sample of mothers largely reported being married (80.8%), being employed (68.5%), and having at least a Bachelor’s level of education (53.4%). Complete demographic data can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Participant Demographic Information

Procedure

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of Central Florida. Mothers were recruited online via MTurk, where the surveys were administered. Participating mothers first reviewed a consent form, for which no identifying information was collected. Following agreement to participate, mothers completed surveys assessing their ACEs, the frequency of their CM experiences, their parenting behaviors, and their attachment with their young children via the measures listed below. Upon completion, mothers were compensated $1.00 for participation in the study. Mothers averaged 37 minutes to complete the study in its entirety.

Measures

Demographics. A brief demographic questionnaire inquired about mothers’ general characteristics regarding themselves and their children (e.g., age, race, ethnicity, occupation).

Mothers’ ACEs. The Adverse Childhood Experience Questionnaire (ACEs; Felitti et al., 1998) assessed the number of ACEs that mothers experienced through their first 18 years. Mothers indicated exposure to each item in a Yes or No format, with the sum of Yes responses yielding a Total score that could range from 0 to 10. The ACEs demonstrated good internal consistency previously (α = .88; Murphy et al., 2014) as well as in the current sample (α =.86).

Mothers’ CM. The 28-item Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ; Bernstein & Fink, 1998) assessed the frequency of CM experiences (i.e., childhood emotional, physical, and sexual abuse and neglect). Mothers rated items on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (Never) to 5 (Very Often). The CTQ demonstrated good internal consistency, reliability, and validity (Scher, Stein, Asmundson, McCreary, & Forde, 2001), with the total CTQ score displaying excellent internal consistency in a previous study (α = .91; Bernstein & Fink, 1998) and in the current sample (α = .92).

Negative Parenting Behaviors. The Alabama Parenting Questionnaire Preschool Revision (APQ-PR; Clerkin, Halperin, Marks, & Policaro, 2007) was used to assess mothers’ current parenting behaviors. The APQ-PR is a revised version of the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (APQ; Frick, 1991) meant for use with parents of preschool-aged children (5-years of age and younger). The 32 items on the APQ-PR are rated on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (Never) to 5 (Always). The Negative Parenting subscale displayed acceptable internal consistency previously (α = .74; Clerkin et al., 2007) and good internal consistency in the current study (α = .84).

Mother-Young Child Attachment. The Experience in Close Relationships scale (ECR; Brennan, Clark, & Shaver, 1998) assessed mothers’ perceptions of their anxious and avoidant attachment with their young children. Given that the ECR was developed originally to measures adult attachment, the ECR was adapted for measuring mother-young child attachment. For example, “I prefer not to show a partner how I feel deep down” was adapted to “My child prefers not to show me how he/she feels deep down.” The ECR contains 36 items that are rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (Disagree Strongly) to 7 (Agree Strongly). The original ECR attachment subscales displayed excellent internal consistency (α = .91 for anxious; α = .94 for avoidant; Brennan et al., 1998). Additionally, the adapted ECR displayed good internal consistency previously (α = .86-.90 for anxious; α = .87-.95 for avoidant; McSwiggan & Renk, 2015) and in this study (α = .88 for anxious; α = .94 for avoidant).

The Caregiving Helplessness Questionnaire (CHQ; George & Solomon, 2011) assessed specifically mothers’ perceptions of disorganized patterns of attachment with their young children. The 25 items on the CHQ are rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not characteristic at all) to 5 (very characteristic). The CHQ’s Mother Helpless (α = .85) and Mother and Child Frightened (α = .66) subscales were related significantly to disorganized attachment and displayed adequate internal consistency previously (Solomon & George, 2011) as well as in the current study (α = .89 and α = .83, respectively).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

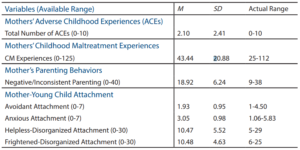

Following screening for violations of missing data, normality, outliers, and linearity, descriptive statistics were examined. In this sample, mothers endorsed an overall low number of ACEs and an overall low to moderate frequency in their CM experiences on the CTQ. Notably, 39 mothers (26.7% of the total sample) endorsed a high number of ACEs (i.e., four or more, as denoted by Felitti et al., 1998). Next, on average, mothers reported moderate levels of negative parenting behaviors on the APQ-PR. Finally, mothers reported overall low avoidant, anxious, helpless-disorganized, and frightened-disorganized patterns of attachment. See Table 2.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics for Variables of Interest.

Correlational Analyses

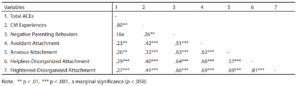

Initially, multicollinearity was assessed to confirm that the variables of interest were not cause for biased regression analyses (Field, 2013). Next, Pearson correlations were examined. As was expected, mothers’ ACEs, CM experiences, mother-young child insecure attachment, and negative parenting behaviors all were correlated positively and significantly (with a marginally significant relationship between ACEs and negative parenting behaviors). See Table 3.

Table 3. Correlations Among Mothers’ ACEs, CM, Negative Parenting Behaviors, and Mother-Young Child Attachment.

Mediational Analyses

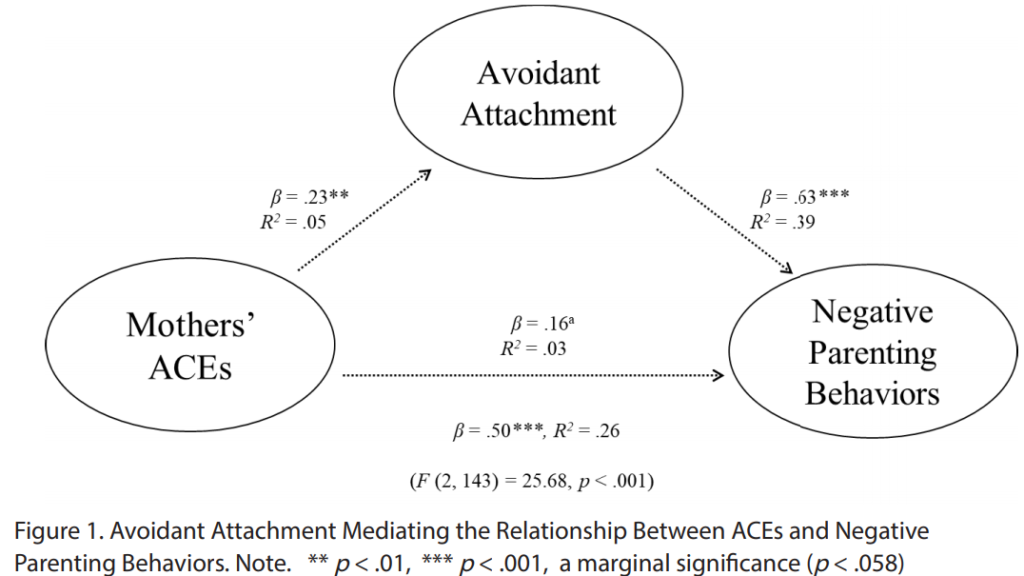

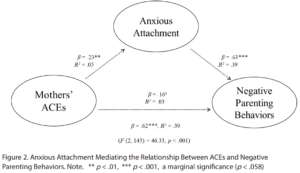

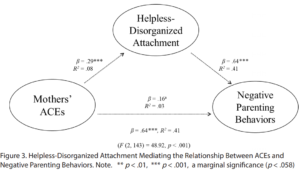

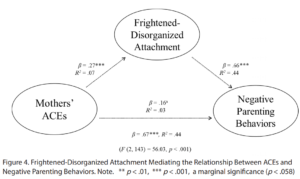

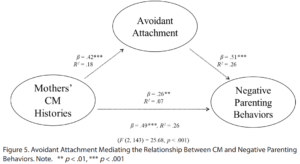

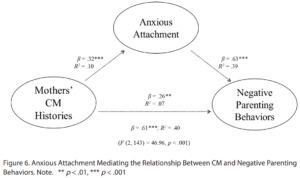

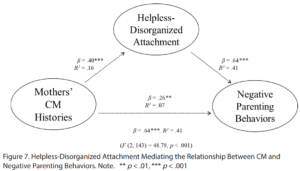

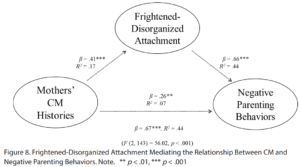

Two series of four mediational analyses each were examined. Either mothers’ ACEs or CM experiences served as the independent variable, the four patterns of mother-young child insecure attachment served as mediators, and negative parenting behaviors served as the dependent variable. Baron and Kenny’s (1986) four-step mediation method was utilized. First, regression analyses would need to confirm that mothers’ ACEs or CM experiences predicted significantly negative parenting behaviors. Second, regression analyses would need to confirm that mothers’ ACEs or CM experiences predicted significantly mother-young child patterns of insecure attachment. Third, regression analyses would need to confirm that mother-young child patterns of attachment predicted significantly negative parenting behaviors. Finally, multiple regression analyses examined mothers’ ACEs or CM experiences and mother-young child patterns of attachment as predictors of negative parenting behaviors to investigate whether mother-young child attachment would demonstrate a mediational pattern. See Figures 1 to 8.

Mothers’ Total ACEs Predicting Negative Parenting Behaviors. Mothers’ total ACEs predicted marginally negative parenting behaviors, F (1, 144) = 3.64, p < .06, R2 = .03. Mothers’ Total ACEs Predicting Insecure Attachment. Mothers’ ACEs predicted significantly all four patterns of mother-young child insecure attachment. Specifically, mothers’ ACEs predicted significantly avoidant attachment, F (1, 144) = 7.78, p < .01, R2 = .05; anxious attachment, F (1, 144) = 7.65, p < .01, R2 = .05; helpless-disorganized attachment, F (1, 144) = 12.73, p < .001, R2 = .08; and frightened-disorganized attachment, F (1, 144) = 11.02, p < .001, R2 = .07, with their young children.

Attachment Predicting Negative Parenting Behaviors. Mother-young child avoidant attachment, F (1, 144) = 51.25, p < .001, R2 = .26, and mother-young child anxious attachment, F (1, 144) = 93.19, p < .001, R2 = .39, predicted significantly negative parenting behaviors. Further, mother-young child helplessdisorganized attachment, F (1, 144) = 98.26, p < .001, R2 = .41, and frighteneddisorganized attachment, F (1, 144) = 112.65, p < .001, R2 = .44, predicted significantly negative parenting behaviors.

Avoidant Attachment Mediating the Relationship between Mothers’ Total ACEs and Negative Parenting Behaviors. Mothers’ total ACEs and mother-young child avoidant attachment predicted significantly negative parenting behaviors, F (2, 143) = 25.68, p < .001, R2 = .26. When entered first, mothers’ total ACEs alone predicted marginally negative parenting behaviors (p < .06). When mother-young child avoidant attachment was added to the equation, total ACEs decreased in significance (p < .56), whereas avoidant attachment served as a significant predictor (p < .001). As such, the relationship between mothers’ total ACEs and negative parenting behaviors was mediated fully and significantly by avoidant attachment.

Anxious Attachment Mediating the Relationship between Mothers’ Total ACEs and Negative Parenting Behaviors. Mothers’ total ACEs and mother-young child anxious attachment predicted significantly negative parenting behaviors, F (2, 143) = 46.33, p < .001, R2 = .39. When entered first, mothers’ total ACEs alone predicted marginally negative parenting behaviors (p < .06). When mother-young child anxious attachment was added to the equation, total ACEs decreased in significance (p < .80), whereas anxious attachment served as a significant predictor (p < .001). As such, the relationship between mothers’ total ACEs and negative parenting behaviors was mediated fully and significantly by anxious attachment.

Helpless-Disorganized Attachment Mediating the Relationship between Mothers’ Total ACEs and Negative Parenting Behaviors. Mothers’ total ACEs and mother-young child helplessdisorganized attachment predicted significantly negative parenting behaviors, F (2, 143) = 48.92, p < .001, R2 = .41. When entered first, mothers’ total ACEs alone predicted marginally negative parenting behaviors (p < .06). When mother-young child helpless-disorganized attachment was added to the equation, ACEs decreased in significance (p < .69), whereas helpless-disorganized attachment served as a significant predictor (p < .001). As such, the relationship between mothers’ total ACEs and negative parenting behaviors was mediated fully and significantly by helpless-disorganized attachment.

Frightened-Disorganized Attachment Mediating the Relationship between Mothers’ Total ACEs and Negative Parenting Behaviors. Mothers’ total ACEs and mother-young child frighteneddisorganized attachment predicted significantly negative parenting behaviors, F (2, 143) = 56.03, p < .001, R2 = .44. When entered first, mothers’ total ACEs alone predicted marginally negative parenting behaviors (p < .06). When mother-young child frightened-disorganized attachment was added to the equation, total ACEs decreased in significance (p < .75), whereas frightened-disorganized attachment served as a significant predictor (p < .001). As such, the relationship between mothers’ ACEs and negative parenting behaviors was mediated fully and significantly by frightened-disorganized attachment.

Mothers’ CM Predicting Negative Parenting Behaviors. Mothers’ CM experiences predicted significantly negative parenting behaviors, F (1, 144) = 9.98, p < .01, R2 = .07.

Mothers’ CM Predicting Insecure Attachment. Mothers’ CM experiences predicted significantly all four patterns of mother-young child insecure attachment. Specifically, mothers’ CM experiences predicted significantly patterns of avoidant attachment, F (1, 144) = 31.21, p < .001, R2 = .18; anxious attachment, F (1, 144) = 16.04, p < .001, R2 = .10; helplessdisorganized attachment, F (1, 144) = 27.63, p < .001, R2 = .16; and frighteneddisorganized attachment, F (1, 144) = 29.27, p < .001, R2 = .17, with their young children.

Attachment Predicting Negative Parenting Behaviors. As stated above, mother-young child avoidant attachment, F (1, 144) = 51.25, p < .001, R2 = .26; anxious attachment, F (1, 144) = 93.19, p < .001, R2 = .39; helpless-disorganized attachment, F (1, 144) = 98.26, p < .001, R2 = .41; and frightened-disorganized attachment, F (1, 144) = 112.65, p < .001, R2 = .44, all predicted significantly negative parenting behaviors.

Avoidant Attachment Mediating the Relationship between Mothers’ CM and Negative Parenting Behaviors. Mothers’ CM experiences and mother-young child avoidant attachment predicted significantly negative parenting behaviors, F (2, 143) = 25.68, p < .001, R2 = .26. When entered first, mothers’ CM experiences predicted significantly negative parenting behaviors (p < .01). When mother-young child avoidant attachment was added to the equation, CM experiences decreased in significance (p < .56), whereas avoidant attachment served as a significant predictor (p < .001). As such, the relationship between mothers’ CM experiences and negative parenting behaviors was mediated fully and significantly by avoidant attachment.

Anxious Attachment Mediating the Relationship between Mothers’ CM and Negative Parenting Behaviors. Mothers’ CM experiences and mother-young child anxious attachment predicted significantly negative parenting behaviors, F (2, 143) = 46.96, p < .001, R2 = .40. When entered first, mothers’ CM experiences predicted significantly negative parenting behaviors (p < .01). When mother-young child avoidant attachment was added to the equation, CM experiences decreased in significance (p < .36), whereas anxious attachment served as a significant predictor (p < .001). As such, the relationship between mothers’ CM experiences and negative parenting behaviors was mediated fully and significantly by anxious attachment.

Helpless-Disorganized Attachment Mediating the Relationship between Mothers’ CM and Negative Parenting Behaviors. Mothers’ CM experiences and mother-young child helpless-disorganized attachment predicted significantly negative parenting behaviors, F (2,143) = 48.79, p <.001, R2 = .41. When entered first, mothers’ CM experiences predicted significantly negative parenting behaviors (p < .01). When mother-young child helpless-disorganized attachment was added to the equation, CM experiences decreased in significance (p < .99), whereas helpless-disorganized attachment served as a significant predictor (p < .001). As such, the relationship between mothers’ CM experiences and negative parenting behaviors was mediated fully and significantly by helpless-disorganized attachment.

Frightened-Disorganized Attachment Mediating the Relationship between Mothers’ CM and Negative Parenting Behaviors. Mothers’ CM experiences and mother-young child frightened-disorganized attachment predicted significantly negative parenting behaviors, F (2, 143) = 56.02, p < .001, R2 = .44. When entered first, mothers’ CM experiences predicted significantly negative parenting behaviors (p < .01). When mother-young child frighteneddisorganized attachment was added to the equation, CM experiences decreased in significance (p < .76), whereas frighteneddisorganized attachment served as a significant predictor (p < .001). As such, the relationship between mothers’ CM experiences and negative parenting behaviors was mediated fully and significantly by frightened-disorganized attachment.

Discussion

Researchers have long thought that investigation of mediating relationships would foster a better understanding of the intergenerational patterns of both ACEs/CM and attachment (Kaufman & Zigler, 1987; Vaillancourt, Pawlby, & Fearon, 2017). Such mediating relationships could help to identify protective factors for those children most at-risk for enduring ACEs and CM experiences at the hands of a parental figure (USDHHS, 2018). Consistently, more work has been needed to uncover the mechanisms that may be driving these relationships (e.g., Vaillancourt, Pawlby, & Fearon, 2017). Thus, the current study investigated the relationships among mothers’ ACEs and CM experiences, mother-young child insecure attachment, and negative parenting behaviors.

As was hypothesized, mediational regression analyses suggested that avoidant, anxious, helpless-disorganized, and frightened-disorganized mother-young child attachment mediated fully and significantly the connections between mothers’ ACEs or CM experiences and their negative parenting behaviors. These findings indicated that mothers’ ACEs and CM experiences predicted most closely mother-young child insecure attachment patterns, which then predicted mothers’ negative parenting behaviors in turn. Interestingly, although insecure attachment followed a mediational pattern in the context of mothers’ ACEs and their negative parenting behaviors, mediational patterns were more robust in the context of mothers’ CM experiences and their negative parenting behaviors. Thus, the chronicity and frequency of CM experiences, in addition to the number of ACEs experienced, may be particularly important for understanding intergenerational patterns. Further, insecure attachment explained 26% to 44% of the variance as a mechanism of action in the relationship between mothers’ ACEs or CM experiences and negative parenting behaviors. These data align with those of Zajac and colleagues’ (2019), who proposed a focus on attachment, rather than on ACEs, in the hopes of identifying those at greatest risk for negative parenting behaviors. Given these findings, secure attachment between mothers and their young children should be examined as a potentially robust protective factor for buffering the risk for negative parenting behaviors in the context of mothers’ ACEs and CM experiences.

Certainly, the findings of this study should be considered in the context of its limitations. Most notably, this study’s cross-sectional design relied entirely on mothers’ self-report data. Along with reporting biases that could be at play, it is imperative to consider the vulnerable nature of the questions included in this study. Relying on self-report alone likely results in an underestimation of the true rates of exposure to ACEs and CM experiences (Shaffer, Huston, & Egeland, 2008). Individuals who perceive their experiences as being “less severe” may be particularly prone to underreporting ACEs and CM (Shaffer et al., 2008). Moreover, fear or bias may prompt mothers to be less than forthcoming when describing maladaptive parenting behaviors with their young children (Pears & Capaldi, 2001). Collectively, mothers may underreport their ACEs and CM experience if they continue to struggle with strong feelings regarding how their ACEs and/or CM experience may be impacting their parenting (Lieberman & Van Horn, 2011). Thus, it may be that mothers in our sample who endorsed fewer ACEs and/or CM experiences also were less likely to endorse difficulties with attachment and parenting. It also must be considered, however, that some mothers, such as those with generally negative views of their lives or those who experience depressive symptomatology in particular, may hold negative views of their childhood experiences as well. Mothers’ holding of negative views across these various domains may translate to discouragement and guilt about parenting, prompting such mothers to be more likely to endorse difficulties with attachment and parenting. Given that the current study cannot disentangle the responses of mothers who underreport versus overreport, future research should seek to examine and understand these potential biases in reporting further.

Given sole utilization of self-report in assessing parenting behaviors and attachment in this study, it is important to note that conclusions can only be drawn regarding mothers’ perceptions of mother young child attachment and their negative parenting behaviors. To further this work, self-report of perceived mother-young child attachment and parenting behaviors should be combined with “gold standard” observational measurements (e.g., the Strange Situation) in future studies. It is recommended that future studies prioritize utilization of validated and multi-method assessment while simultaneously creating a safe environment in which participants may openly discuss their ACEs and/or CM experiences and their parenting. Although a recent meta-analysis concluded that support for the intergenerational transmission of ACEs and CM does not vary with methodological quality (Madigan et al., 2019), use of more in-depth data collection (e.g., longitudinal designs) and analytic techniques (e.g., structural equation modeling) may allow for further exploration of causal relationships among the variables.

An additional limitation lies in the lack of diversity within our relatively homogeneous, low-risk sample. Specifically, mothers were predominantly Caucasian, married, college-educated, and of middle-class socioeconomic status. These demographic characteristics unquestionably compromise external validity for samples who are more diverse with regard to their ethnic/cultural backgrounds, education, and socioeconomic status. Additionally, approximately 26.7% of the sample (i.e., 39 mothers) reported exposure to four or more ACEs (i.e., a high level of ACEs), suggesting that this sample was relatively low-risk overall. Although previous studies demonstrated significant findings from much lower percentages of high levels of ACEs (e.g., 6%; Felitti et al., 1998), there would be significant utility in focusing on high-risk parents in future studies (e.g., Zajac et al., 2019). In particular, future studies may consider the comparative relationships of ACEs/CM, parenting behaviors, and attachment across community samples of parents and foster parents, adoptive parents, and parents who are child welfare- and/or substance involved.

In investigating potential ports of entry to break intergenerational cycles of ACEs and CM experiences, there are additional factors outside of mother-young child attachment that were not explored in the scope of this study. For instance, research found that having a supportive romantic partner and low levels of intimate partner violence buffered against the intergenerational cycle of abuse (Jaffee et al., 2013). Additionally, mothers’ ability to recall more positive childhood experiences with their caregivers buffered intergenerational transmission of their own trauma (Narayan, Ghosh Ippen, Harris, & Lieberman, 2019). Moreover, factors including type(s) of ACEs or CM experiences, sociodemographic factors, child age and gender, mothers’ age, reflective functioning, substance use, residential stability, social support, coping style, and mothers’ mental health, among others (Narayan et al., 2019; Savage, Tarabulsy, Pearson, Collin-Vézina, & 2019; St. Laurent, Dubois-Comtois, Milot, & Cantinotti, 2019), may potentially influence the cycle of ACEs and CM experiences.

The findings of the current study may have significant implications for trauma-informed parenting and parentyoung child interventions. In particular, interventions that introduce attachment focused concepts, support the facilitation of mother-young child secure emotional connections, and combat insecure attachment may produce meaningful intervention effects in the context of mothers’ ACEs and CM experiences. For example, Circle of Security-Parenting, which emphasizes concepts such as “following the child’s lead” and “being with” young children in their emotions, has promoted shifts from insecure and disorganized attachment to secure attachment classifications in high-risk young children (Hoffman, Marvin, Cooper, & Powell, 2006). Similarly, by focusing on nurturance and synchrony, Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-Up (ABC) has promoted increased parent sensitivity to young children’s signals and decreased negative parenting behaviors using “inthe-moment” coaching (Bernard, Meade, & Dozier, 2013). Additionally, in mothers who experienced ACEs, the Group Attachment Based Intervention (GABI) showed medium to large effect sizes in improving mother-young child reciprocity, increasing mothers’ presence, and decreasing hostile parenting and child maltreatment risk relative to the outcomes of a control group (Steele, Murphy, Bonuck, Meissner, & Steele, 2019). Finally, in facilitating reflection of protective factors with caregivers (i.e., ‘angels in the nursery’ or positive ‘angel memories’), Child-Parent Psychotherapy (CPP) buffered the intergenerational transmission of trauma from mothers to their young children (Narayan et al., 2019). By intervening through different ports of entry that can provide access to parents’ recollections of their own ACEs and CM experiences, their attachment to their young children, and any negative behaviors that they may exhibit, the intergenerational cycle of ACEs and CM experiences can be broken.

References

Banyard, V. L., Williams, L. M., Siegel, J. A. (2003). The impact of complex trauma and depression on parenting: An exploration of mediating risk and protective factors. Child Maltreatment, 8(4), 334-349.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173-1182.

Bernard, K., Meade, E. B., & Dozier, M. (2013). Parental synchrony and nurturance as targets in an attachment-based intervention: Building upon Mary Ainsworth’s insights about mother–infant interaction. Attachment & Human Development, 15(5-6), 507-523.

Bernstein, D., & Fink, L. (1998). Childhood Trauma Questionnaire: A retrospective self-report. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation.

Berthelot, N., Ensink, K., Bernazzani, O., Normandin, L., Luyten, P., & Fonagy, P. (2015). Intergenerational transmission of attachment in abused and neglected mothers: The role of trauma‐specific reflective functioning. Infant Mental Health Journal, 36(2), 200-212.

Booth, C. L., Rose-Krasner, L., & Rubin, K. H. (1991). Relating preschoolers’ social competence and their mothers’ parenting behaviors to early attachment security and high-risk status. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 8, 363-382.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Volume I, Attachment. New York: Basic Books.

Brennan, K., Clark, C., & Shaver, P. (1998). Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In J. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 46-76). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Clerkin, S. M., Marks, D. J., Policaro, K., & Halperin, J. M. (2007). Psychometric properties of the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire-Preschool Revision. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 36(1), 19-28.

Cyr, C., Euser, E. M., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2010). Attachment security and disorganization in maltreating and high-risk families: A series of meta-analyses. Developmental Psychopathology, 22(1), 87-108.

Dykas, M. J., & Cassidy, J. (2011). Attachment and the processing of social information across the life span: theory and evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 137(1), 19-46.

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, E., …Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14, 245-258.

Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. (4th ed). London: Sage.

Fonagy, P., Steele, H., & Steele, M. (1991). Maternal representations of attachment during pregnancy predict the organization of infant-mother attachment at one year of age. Child Development, 62(5), 891-905.

Fraiberg, S., Adelson, E., Shapiro, V. (1975). Ghosts in the nursery: A psychoanalytic approach to the problems of impaired infant-mother relationships. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 14(3), 387–421.

Frick, P. J. (1991). The Alabama Parenting Questionnaire. Unpublished Instrument: University of Alabama.

George, C., & Solomon, J. (2011). Caregiving helplessness: The development of a screening measure for disorganized maternal caregiving. In J. Solomon & C. George (Eds.), Disorganized attachment and caregiving (pp. 133-166). New York: Guilford.

Hoffman, K. T., Marvin, R. S., Cooper, G., & Powell, B. (2006). Changing toddlers’ and preschoolers’ attachment classifications: The Circle of Security intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(6), 1017.

Iyengar, U., Kim, S., Martinez, S., Fonagy, P., & Strathearn, L. (2014). Unresolved trauma in mothers: Intergenerational effects and the role of reorganization. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1-13.

Jaffee, S. R., Bowes, L., Ouellet-Morin, I., Fisher, H. L., Moffitt, T. E., Merrick, M. T., & Arseneault, L. (2013). Safe, stable, nurturing relationships break the intergenerational cycle of abuse: A prospective nationally representative cohort of children in the United Kingdom. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(4), S4-S10.

Jones, J. D., Cassidy, J., & Shaver, P. R. (2015). Parents’ self-reported attachment styles: A review of links with parenting behaviors, emotions, and cognitions. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 19(1), 44-76.

Kaufman, J., & Zigler, E. (1987). Do abused children become abusive parents? American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 57(2), 186-192.

Khan, M., & Renk, K. (2018). Understanding the pathways between mothers’ childhood maltreatment experiences and patterns of insecure attachment with young children via symptoms of depression. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 49(6), 928-940.

Khan, M., & Renk, K. (2019). Mothers’ adverse childhood experiences, depression, parenting, and attachment as predictors of young children’s problems. Journal of Child Custody, 16(3), 268-290.

Lang, A., Garstein, M., Rodgers, C., & Lebeck, M. (2010). The impact of maternal childhood abuse on parenting and infant temperament. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 23(2), 100-110.

Lieberman, A. F., & Van Horn, P. (2011). Psychotherapy with infants and young children: Repairing the effects of stress and trauma on early attachment. New York: Guilford.

Madigan, S., Cyr, C., Eirich, R., Fearon, R. P., Ly, A., Rash, C., … & Alink, L. R. (2019). Testing the cycle of maltreatment hypothesis: Meta-analytic evidence of the intergenerational transmission of child maltreatment. Development and Psychopathology, 31(1), 23-51.

McSwiggan, M., & Renk, K. (2015). Differential parenting and parents’ perceptions of their children: Can attachment help explain this relationship? (Unpublished master’s thesis). University of Central Florida, Orlando, FL.

Murphy, A., Steele, M., Dube, S. R., Bate, J., Bonuck, K., Meissner, P., … Steele, H. (2014). Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) questionnaire and adult attachment interview (AAI): Implications for parent-child relationships. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(2), 224-233.

Narayan, A., Ippen, C., Harris, W., & Lieberman, A. (2019). Protective factors that buffer against the intergenerational transmission of trauma from mothers to young children: A replication study of angels in the nursery. Development and psychopathology, 31(1), 173-187.

Pears, K. C., & Capaldi, D. M. (2001). Intergenerational transmission of abuse: A two generational prospective study of an at-risk sample. Child Abuse & Neglect, 25(11), 1439-1461.

Savage, L. É., Tarabulsy, G. M., Pearson, J., Collin-Vézina, D., & Gagné, L. M. (2019). Maternal history of childhood maltreatment and later parenting behavior: A meta-analysis. Development and Psychopathology, 31(1), 9-21.

Scher, C. D., Stein, M. B., Asmundson, G. J., McCreary, D. R., & Forde, D. R. (2001). The childhood trauma questionnaire in a community sample: Psychometric properties and normative data. ournal of Traumatic Stress, 14(4), 843-857.

Shaffer, A., Huston, L., & Egeland, B. (2008). Identification of child maltreatment using prospective and self-report methodologies: A comparison of maltreatment incidence and relation to later psychopathology. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32(7), 682-692.

Solomon, J., & George, C. (Eds.). (2011). Disorganized attachment and caregiving. Guilford.

Spieker, S. J., Bensley, L., McMahon, R. J., Fung, H., & Ossiander, E. (1996). Sexual abuse as a factor in child maltreatment by adolescent mothers of preschool aged children. Development and Psychopathology, 8(3), 497-509.

Steele, H., Murphy, A., Bonuck, K., Meissner, P., & Steele, M. (2019). Randomized control trial report on the effectiveness of Group Attachment-Based Intervention (GABI©): Improvements in the parent–child relationship not seen in the control group. Development and Psychopathology, 31(1), 203-217.

St-Laurent, D., Dubois-Comtois, K., Milot, T., & Cantinotti, M. (2019). Intergenerational continuity/ discontinuity of child maltreatment among low-income mother–child dyads: The roles of childhood maltreatment characteristics, maternal psychological functioning, and family ecology. Development and Psychopathology, 31(1), 189-202.

Thornberry, T. P., Knight, K. E., & Lovegrove, P. J. (2012). Does maltreatment beget maltreatment? A systematic review of the intergenerational literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 13(3), 135-152.

US. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS), Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. (2018). Child maltreatment 2016. Available from: www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/cm2016.pdf.

Vaillancourt, K., Pawlby, S., & Fearon, R. (2017). History of childhood abuse and mother-infant interaction: A systematic review of observational studies. Infant Mental Health Journal, 38(2), 226-248.

van IJzendoorn, M. H. & Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J. (2019). Bridges across the intergenerational transmission of attachment gap. Current Opinion in Psychology, 25, 31-36.

Widom, C. S., Czaja, S. J., & DuMont, K. A. (2015). Intergenerational transmission of child abuse and neglect: Real or detection bias? Science, 347 (6229), 1480-1485.

Zajac, L., Raby, K. L., & Dozier, M. (2019). Attachment state of mind and childhood experiences of maltreatment as predictors of sensitive care from infancy through middle childhood: Results from a longitudinal study of parents involved with Child Protective Services. Development and Psychopathology, 31(1), 113-125.

Authors

Maria Khan, MS and Kimberly Renk, PhD

United States

Please address correspondence concerning this article to: Kimberly Renk, Ph.D., University of Central Florida, Department of Psychology, P.O. Box 161390, Orlando, Florida, USA, 32816. E-mail: Kimberly.Renk@ucf.edu