Introduction: Child on the rainbow: Real life stories of parents to children with disabilities

By Dalia Shlomy (Israel) and Maree Foley (Switzerland)

For many parents, the birth of a new baby brings joy and wonderment with the ensuing challenges of caring for a totally dependent new bundle of a person. However, “nearly 4% of parents receive distressing news about their child’s health” (Barnett, Clements, Kaplan-Estrin & Fialka, 2003, p. 184).

Understanding parents’ experiences of receiving a long-term health diagnosis of their infant and or young child, in relation to the diagnostic and prognostic nature of the child’s health challenges, is vital. It is vital because this understanding helps to ensure the practitioner optimally provides the conditions within which to provide a secure space for the parents, with their baby, to explore and grow together in their parent-child-family-community-relationships.

Moreover, as Carpenter (2005) states:

At the point of diagnosis of a child’s disability, a parent’s first question is hardly likely to be about the local early childhood intervention services. These families are frightened, disturbed, upset, grieving and constantly vulnerable. The role of the professionals involved with them is to catch them when they fall, listen to their sorrow, dry their tears of pain and anguish, and, when the time is right, plan the pathway forward. (p. 181)

The following two papers provide readers with a window into the experiences of parents to children with disabilities: their stories. The first paper is by Dalia Shlomy (Israel) who describes her journey as an initiator, group counsellor, and producer of the play, Child on the Rainbow; a play by parents of children with special needs (Shlomy, 2014). Link to watch the play: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lJjjBelYpt4&t=17s

The second paper, by Dalia Shlomy and Maree Foley with the parents, features the voices of the parents who participated in the group work and then who were actors in the play, Child on the Rainbow. The parents, whose children are now grown up, reflect specifically, on the very early days of learning about the challenges their baby faced and how they adapted to parenting a baby with a diagnosis. This paper also includes a brief exploration of the Reaction to Diagnosis Interview (RDI) (Marvin & Pianta, 1996).

On behalf of the Perspectives team and the WAIMH community we are grateful to every parent who has generously shard their stories with Dalia, their local communities, and now with our global WAIMH community.

References

Barnett, D., Clements, M., Kaplan-Estrin, M. & Fialka, J. (2003). Building new dreams. Supporting parents’ adaptation to their child with special needs. Infants and Young Children, 6 (3), 184-200.

Carpenter, B. (2005). Early childhood intervention: possibilities and prospects for professionals, families, and children. British Journal of Special Education, 32 (4), 176-183.

Marvin R. S. & Pianta R. C. (1996). Mothers reaction to their child’s diagnosis: relation with security of attachment. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 25 (4), 436-445.

Child on the Rainbow: Real life stories of parents to children with disabilities. A play accompanied with music, songs, and humour

By Dalia Shlomy (Israel) (Initiator, Group Counsellor, and Producer)

My name is Dalia Shlomy and I want to tell you about the processes that led me to creating the play: “A child on the Rainbow Real life stories of parents to children with disabilities. A play accompanied with music, songs, and humour”.

I began my career as a paediatric nurse. I remember very well all the times when I had to say out loud that there is a problem with the size of the child’s head. I remember the mother who burst into tears and the mother who said to me, “Nonsense, the child is okay.”

I remember my emotional upheaval at the time, the hope that maybe everything is fine, the understanding that now it was necessary to act and the anger at the parents who did not act or disappeared.

Later I went to work in programs to locate children at risk, and many times I stood (with the rest of the team) against parents who found it difficult to adapt to the reality of their child and we – the professional team, arguing among us about how to deal with such parents. It was only during my master’s degree at Haifa University that I was exposed to the concept of, challenges to adapting to child diagnoses and realized that accepting was a process, and I had to accept the process.

In addition to my professional work, I deal with production of events that combine personal stories and poetry. I do this together with my friend who is a musician and a mother of a child with special needs. In one of the conversations between us the question arose: Why not tell the story of parents of children with special needs?

A group of parents and myself as the counsellor, started to meet once a week (I am parent groups counsellor) to expose the difficulties and pains associated with raising a child with disabilities. We used a playback theatre technique that made it possible to touch sensitive points with the required sensitivity. My attachment to the parents gradually increased and their confidence in me grew. The ability to touch pain without fear made it possible to reveal more experiences and events, from the daily life of the parents. I believe that part of my ability to connect with parents even though I am not a parent of a child with special needs, is related to my personal experience of loss and pain. From my painful place, I could understand their painful place.

After a year and a half of meetings that were all documented, we decided to go forward and invite a director, who would help turn the raw material into texts adapted to the stage. At this point, I began to use my abilities as a producer. After another year and a half, the premier took place on the 6th of February 2014.

An important part of the play is the dialogue which takes place between the actors and the audience. The importance of this dialogue; the empowerment experienced, by both parents and professionals.

It has been five years since the Premier took place. The play has been performed more than 20 times and we will continue to appear, as long as we can. Today we are a cohesive group with our own humour and shared experiences. Formally, my role is production, in practice; I feel like the group’s big mummy and feel great pride in the group’s achievements.

The personal processes of the group members are evident mainly in openness and in the ability to reveal their personal stories. One of the members participated in a national television program dealing with parenting of children with special needs, another found that the stage suited him. Me? I’m happy taking part in all this.

Link to watch the play: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lJjjBelYpt4&t=17s

Credits

Dalia Shlomy – Initiator, Group Counselling and Producer

Dr Efrat Sher-Censor – Academic Counselling

Hani Lavi Balin – Director

Liora Bloch- Initiator, Musical producing, Plays the Guitar and Sings

Soof Sela – Piano and Singing

Dror Yifa, Mira Fahima, Smadar Safrai, Anat Bruner, Liora Bloch – Actors (parents)

Tsafi Kurz Harpaz – Photography

capNsub – Subtitles

Child on the Rainbow: Parents talk about what it is like to receive a diagnosis of disability of their babies and toddlers

By Dalia Shlomy, Maree Foley, Dror Yifa, Mira Fahima, Smadar Safrai, Anat Bruner and Liora Bloch

This paper is aimed to support practitioners and clinicians to further understand the parents’ experiences of receiving a diagnosis of disability concerning their child. Drawing on the work of Dalia Shlomy and the parents engaged with “Child on the Rainbow” (2014), this paper offers a window into the lives of the babies and young children, with their parents, and in relationship with their community.

In summarizing, how the Child on the Rainbow (2014) project came about, Dalia Shlomy reflected:

The play, “Child on the Rainbow”, was created through a relationship between a parent group counsellor and a music teacher, who was also a parent of a child with special needs. From this beginning, of two people, the idea was welcomed by a group of parents to children with special needs. These parents were members of the “Alei Cotert” club operating in the Izrael Valley regional council in Israel.

The raw material for the play evolved from one and half years of playback theatre recordings within which the group explored personal difficulties associated with raising a child with special needs, and with the support of the group, the ensuing journey towards peace and acceptance; of the diagnosis, of their child and of their relationship with their child. Next (which took a further one and half years) a professional director transformed the raw material into a 9-scene play.

Each scene tells a parents’ story of their experiences of, for example, coming to terms with the diagnosis, shame, family relationships, society’s attitudes, and prejudices. The play also contains poetry, including one piece written by Chanoch Levin (A known Israeli play writer). You can watch the play from the following link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lJjjBelYpt4&t=17s

In preparation for this paper, Maree asked Dalia, if it would be possible to hear more from the parents who feature in the Child of the Rainbow, about their early days with their infants and toddlers; who are now grown up. Upon this request via Dalia, the parent’s generous responses, shape the heart of this paper. Within the translation from Hebrew to English, as much as possible, we have not changed or overly edited the parent’s stories. In doing so, our intention has been to bring into view the voice of the parent, as if we were sitting together, listening to these remarkable people, remarkable parents. We begin with Mira and Barak’s story.

Mira and Barak’s story

Barak was our fourth child. After two girls and one boy I thought I know everything about children and parenthood, but then Barak was born and changed all my ideas. He was a very happy child, did not cry at all but he was very active. Then I noticed that he is not doing what he should do, the first thing was to follow after a moving object. He was looking straight without following with his eyes.

The Doctor sent us to a special test, and they told me that biologically everything is all right. Maybe it’s a matter of slow development.

As the years passed, we noticed that everything was a slow process. He was late standing, late walking, and slow speaking. It took him some years to start speaking. At the age of 3 he still did not speak. Everyone around us comforted us that times will come that we’d like him to stop talking.

Today he is speaking fluently, but still got problems of pronounce everything right.

The super hyper – activity was shown at the age of 4, when he went to the kindergarten. All the children could sit very quietly listening to their kindergarten teacher, but Barak could not sit. After few minutes he felt that he must walk or run. This, of course was a kind of an interruption at the kindergarten. They wanted to give him the medicine RITALIN, but we objected to give him this medicine because it is a psychiatric type.

I still remember that during all his childhood I was in some kind of struggle, all the time, against the education team. I felt that I am his voice and representing his rights.

The main thing I was doing in that period is running after every idea or every new method that can help him or cure him. I was absolutely sure that along the time he will be okay and that he will be involved in the lives of his peers.

That never happened.

Till now he is suffering from lack of friends and he is a very lonely guy.

My name is Mira and my son BARAK is 34 years old.

As we think about Barak, now 34 years old and his mother Mira, their story illustrates the connections between child, family, and community. Further highlighting this point, Falik (1995) reminds us that an infant and or young child’s diagnosis is at least a triadic experience including the child, their family, and the community.

Furthermore, in response to a diagnosis, the literature uses terms such as resolution and non-resolution (Marvin & Pianta,1996). Based on phenomenological studies of parents, Heiman (2002) found resilience, coping and future expectations as core features to appreciate in the process. Barnett et al. (2003), consider the process of adaptation to better encapsulate the parents’ experiences over time:

We define adaptation as an ongoing process whereby parents are able to sensitively read and respond to their child’s signals in a manner conducive to healthy development… we contend that parental perceptions, thoughts, and emotional reactions to their child’s condition are effective avenues for promoting adaptation. (Barnett et al., 2003, p. 184)

In day-to-day terms Barnett et al (2003) state that “healthy adaptation” (p. 197) is central to the development of the quality of the attachment relationship.

Ideally, parents increasingly are able to learn to love, appreciate … their child. As the child develops a secure attachment, the parent and child are able to build new …. Dreams together. (Barnett et al., 2003, p. 197)

In addition, much has been researched regarding the corelation between a parents reactions and capacities in response to the diagnosis, their caregiving, and their unique infant-parent attachment relationships (Oppenheim et al., 2007; Sher-Censor, Doley, Said, Baransi & Amara, 2017; Sher-Censor, Ram-On, Rudstein-Sabbag, Watemberg, & Oppenheim, 2020).

Furthermore, as the parents voices below indicate, diagnosis can enter the lives of a family at different ages and developmental stages. Indications that prompt a health inquiry in infants and toddlers is required, is not always evident at birth. Within this amazing group of parents, some did not enter the world of diagnosis until their children were older. Continuing the conversation begun by Mira and Barak’s story, we now have the opportunity, to listen to the stories of: Smadar and Lishay; Dror and their son; Anat and her daughter; and Liora and Ofri.

Smadar and Lishay: Their story

This is the story of Lishay our first-born child.

We were a happy young couple with a normal pregnancy excited to become a family.

Lishay was born on the 38th week of the pregnancy in a cesarean section due to complications that left him barely alive.

The doctors managed to save his life, but they informed us that Lishay had suffered severe damage in large areas of his brain.

It was so severe that they couldn’t tell us if he would be able to walk talk or see…

With this uncertainty we began our journey.

From the very beginning, Lishay proved to be a strong and optimistic character.

Three times a week he was practicing physical therapy as well as speech therapy and although it was pretty intensive, he always smiled and did it over and over again.

At the age of two and four months after endless falls and injuries, Lishay began to walk!!!

There are no words to describe how happy and proud he was… (as us)

We learned that Lishay has no limitations and he kept surprising us with his achievements.

Lishay walks, talk’s, sees with a very strong life, loving personality, keeps smiling to the world, even if the world doesn’t always smile back to him.

Having a child like Lishay and the journey we share together, has made me a better stronger person, not afraid to face any challenges life may bring my way.

Lishay opened my eyes and soul and there is not a day gone by without me being enriched by him.

The meaning of the full name Lishay Tuvia that we chose for him before he was born, in Hebrew is: my God grace gift, which amazingly was profiled!

SMADAR PROUD MOM

Dror and their son

Our son was diagnosed when he was around 11 years old on the autistic spectrum. Till then he was functioning almost as his friends. Although he seldom invited friends or was invited by them, we never thought that he straggles Asperger Syndrome. We noticed it only some years later, so we didn’t deal the subject the first years.

Anat and her daughter

In the first few months, I did not notice any particular difficulty. A beautiful baby, sleeps well, eats well. She didn’t smile or laugh, but I didn’t understand what that meant. Towards the age of one year, I began to be disturbed. She didn’t murmur at all. When I showed her pictures in the book, she couldn’t point to things I showed her.

After age one year she could not follow a simple instruction. I was more troubled but didn’t think in terms of a “problem”. As she is the fourth child in the family and as the signs of something going wrong increased, the worry grew. We checked hearing, vision, everything is fine. My concern grew more and more disturbing and frightening: what was happening to her? What is the problem? What will it be?

At the age of two and three quarters, we reached a developmental physician. She spoke about Slow Development. Since it was not a Developmental disability, I felt rather encouraged that the gap would be closed later. In spite of treatments at the speech therapist and occupational therapist, this did not happen. The gap between her and same age children, especially in understanding the language and social codes, grew wider. The anxiety of not knowing what the definition of her problem is, was actually increased.

At age 5, we were still in that situation. We were looking for all kinds of therapists and ways to help and promote her. Every afternoon, I, her mother, was busy playing with her and teaching her how to play.

Liora and Ofri

It started with a fever seizure. Ofri (second child in the family) was one year and five months old. There was something in the air before. There was a feeling that something in the development, wasn’t quite right – but the problem was hard to pinpoint.

Losing his consciousness during the seizure was, for me, an experience of a mother who lost her child. I thought he was gone. It was a silent shock to me. I vividly remember my wonder when I heard him cry and realized he was alive. My mother told me at the end of that day that I had aged ten years in a day. I was 33 at the time.

An entanglement of hospitalizations, tests and diagnoses began. The seizures were repeated and in fact, Epilepsy and Slow Development were diagnosed. I remember very well, how heroic, brave, I was at the time of hospitalization – and on the contrary, the fall of spirit when we returned home. But the fall was short. No more than a few hours. We were surrounded by an extremely supportive extended family and friends who were equally helpful.

Ofri began medication treatment that disrupted all his systems. He was confused, hyper-active. We had to keep an eye on him at all times. There was a therapeutic set of routines we needed to keep. And in spite of all this, at home the joy of living never ceased. We dealt with the situation with a lot of humour and most of all in his acceptance and exposure outside in the most transparent way.

Time went by. At the age of six, a Comprehensive Diagnostics was performed, at the end of which came the bad news – Ofri suffers from light Mental Retardation.

This letter was a slap in the face. It was the first time it was written in black and white.

One had to deal with the absolute knowledge that it was not something that will go away, the various treatments might improve his function – but in fact it was our child who would never be “normal”.

I remember when Ofri was about three years old, we went to a family holiday dinner at my parents’ home. How much I cried on the way. This thought that everyone comes with their healthy children – and we are taking care of a sick child with a mountain of related problems.

Looking back – it was hard, but we made a wonderful journey.

And the proof is – this is a 30-year-old, communicative and happy guy, high-functioning, independent, earning a living, his world is full of good and mostly – and most importantly – happy.

While we pause to take in the power, pain, and hope, of these lived stories, it is difficult to know exactly how to move from here, back into theory. But in fact, that is one of the steps of the dance we do together as parents and children with professionals, and as professionals, with parents and their children.

One way that does seem to bridge these different lenses on understanding, is the Reaction to Diagnosis Interview (RDI) (Marvin & Pianta, 1996). The RDI offers a meaningful and structured way to learn and discover together about the journey so far. Of note, the RDI has been adapted to a shorter self-report form of the “Reaction to Diagnosis Questionnaire” (RDQ) (Sher-censor et al., 2020).

A useful, brief summary of the RDI is provided below. It was used as part of a training promotion, presented by Marvin (2013) in Italy:

The Reaction to Diagnosis Interview (RDI) (Pianta & Marvin, 1992) is a brief, 15-minute interview, derived in part from Mary Main’s concept of “resolution of trauma or loss” originally developed as part of the Adult Attachment Interview (George, Kaplan & Main, 1985). The RDI examines resolution of the potential loss/trauma associated with the experience of learning that one’s child has a disability or chronic illness. Parents report this to be a period of crisis: the family’s routines are disrupted, expectations for the child may be challenged, the parent may feel guilty or may search for a very personal reason/cause, and their sense of themselves as effective parents is challenged. Parents vary in their reports of the diagnostic experience and its aftermath, in their ability to reflect on these experiences, and in their ability to turn their attention to the present and future regarding their child. In other words, parents vary in the degree to which they are able to resolve the crisis of the diagnosis. The RDI assesses this resolution or lack of resolution through videotaping and then coding an individual parent’s responses to 6 standardized questions with specific probes. The interview requires 10-20 minutes to administer, and 30-40 minutes for an experienced and certified professional to code. The coding yields major classifications of Resolved and Unresolved, plus a number of sub-classifications within each major classification. These sub-classifications are helpful in the coding process, and are useful for planning and conducting interventions (http://www-5.unipv.it/users/aip2014/images/1.RDIWorkshopFlyer-Pavia2013.pdf)

To further elaborate, interview questions within the RDI (Marvin & Pianta,1996) include:

- When did you first realize that your child had a medical problem (probe for details)?

- What were your feelings at the time of this realization?

- How have these feelings changed over time?

- Tell me exactly what happened when you learned of your child’s diagnosis. Where were you, who else was there, what were you thinking and feeling at that moment?

- Parents sometimes wonder or have ideas about why they have a child with special needs. Do you have anything like that that you wonder about?

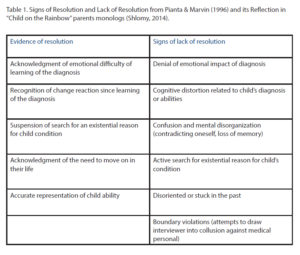

Analysing the Reaction to Diagnosis Interview results (as shown in Table 1) we can understand the parent’s place in relation to the diagnosis and adapt our professional counselling to the parent situation. Parents who have come to terms with the diagnosis will demonstrate emotional change, acceptance, hope, and will deal with the cause of the difficulty. Parents who have not yet come to terms with the diagnosis may exhibit one of the following signs: emotional detachment, emotional flooding, anger, depression, disorganization, cognitive distortion, and confusion.

Conclusion-Pause

Carpenter (2005) states:

At the point of diagnosis of a child’s disability, a parent’s first question is hardly likely to be about the local early childhood intervention services. These families are frightened, disturbed, upset, grieving and constantly vulnerable. The role of the professionals involved with them is to catch them when they fall, listen to their sorrow, dry their tears of pain and anguish, and, when the time is right, plan the pathway forward. (p. 181)

As we find a place to conclude, it seems more apt to consider this as a place to pause because the conversations, the experiences for the parents and their now adult children, is ongoing, daily. Throughout the Child in the Rainbow project, Dalia Shlomy has managed to artfully bridge theory with practice while keeping the heart of our work, babies with their parents in their communities, at centre stage. The play, Child on the Rainbow has been performed more than 20 times during the past five years in front of parents and professionals together. And furthermore, after the final applause, what happens next at each show: an open discussion between Dalia Shlomy as the producer, the parents who are the actors in the show, and the audience. So, it seems apt to pause here, before we invite your enquiry and conversation, with a word of thanks to each parent and their child:

Mira and Barak, Thank you.

Smadar and Lishay, Thank you.

Dror and their son, Thank you.

Anat and her daughter, Thank you.

Liora and Ofri, Thank you.

References

Barnett, D., Clements, M., Kaplan-Estrin, M. & Fialka, J. (2003). Building new dreams. Supporting parents’ adaptation to their child with special needs. Infants and Young Children, 6 (3), 184-200.

Carpenter, B. (2005). Early childhood intervention: possibilities and prospects for professionals, families, and children. British Journal of Special Education, 32 (4), 176-183.

Fialk, L. H. (1995). Family patterns of reaction to a child with learning disability: A mediational perspective. Journal of Learning and Disability, 28, 343-363.

Marvin, R. S. (2013) The Reaction to Diagnosis Interview (RDI) Training An Evidence-Based Clinical Assessment Course Flyer. Pre-Conference Workshop, August 27th – 29th Pavia, Italy (http://www-5.unipv.it/users/aip2014/images/1.RDIWorkshopFlyer-Pavia2013.pdf)

Marvin R. S. & Pianta R. C. (1996). Mothers reaction to their child’s diagnosis: relation with security of attachment. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 25 (4), 436-445.

Oppenheim, D., Dolev, S., Koren-Karie, N., Sher-Censor, E., Yirmiya, N., & Salomon, S. (2007). Parental resolution of the child’s diagnosis and the parent-child relationship. In D. Oppenheim & D. F. Goldsmith (Eds.), Attachment theory in clinical work with children: Bridging the gap between research and practice (pp. 109–136). New York: Guilford.

Sher-Censor, E., Dolev, S., Said, M., Baransi, N., & Amara, K. (2017). Coherence of representations regarding the child, resolution of the child’s diagnosis and emotional availability: A study of Arab-Israeli mothers of children with ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47, 3139–3149.

Sher-Censor, E., Ram-On, T. D., Rudstein-Sabbag, L., Watemberg, M., & Oppenheim, D. (2020) The reaction to diagnosis questionnaire: a preliminary validation of a new self-report measure to assess parents’ resolution of their child’s diagnosis. Attachment & Human Development, 22 (4), 409-424, DOI: 10.1080/14616734.2019.1628081

Shlomy, D. (Producer) & Lavi Bellin, H. (Director) (2014). Child on the Rainbow: A show by parents of children with special needs. Israel.

Authors

Dalia Shlomy, Maree Foley, Dror Yifa, Mira Fahima, Smadar Safrai, Anat Bruner and Liora Bloch