Introduction

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is an infectious disease, declared by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a pandemic on March 2020. By September 2020, there were more than 30 million confirmed cases spread beyond 180 countries and territories around the world (WHO, 2020). In this context, several measures were adopted by national authorities to limit the global transmission of disease. Collective control measures were introduced that included specific recommendations for risk groups, including pregnant women (CDC, 2020).

In Portugal, during the COVID-19 state of emergency lockdown (active from 18th March to 2nd May 2020), healthcare resources were reorganized in response to the pandemic, involving the reallocation of services and the suspension of non-urgent medical activities. In this context, Portuguese pregnant women had prenatal appointments, routine exams and ultrasounds cancelled, and companions were no longer allowed during labour and postpartum. For women who tested positive for COVID-19, protective measures initially recommended no skin-to-skin contact between the mother and the baby, wastage of all breastmilk and separation between infected mothers and the newborns (DGS, 2020). These measures were intended to mitigate the spread of the disease but might have had a possible negative impact on the mental health of this vulnerable population.

Mental health problems, including depression and anxiety disorders, are relatively common among women of reproductive age, affecting nearly one in every five individuals (Charlson et al., 2019; Kendig et al., 2017). During the perinatal period, evidence suggests that the global prevalence of these mental disorders may increase up to 25%, with relevant morbidity features experienced by the mother throughout the pregnancy and the post-partum period, especially amid stressful or traumatic events (Howard et al., 2014; Howard et al., 2018). Accordingly, perinatal depression is now considered one of the most common medical complications of pregnancy reaching 10-15% of incidence (Woody, Ferrari, Siskind, Whiteford, & Harris, 2017).

A recent meta-analysis suggests an overall prevalence of any anxiety disorder during the perinatal period of more than 15% (Dennis, Falah-Hassani, & Shiri, 2017). When left untreated, these conditions are possibly linked to obstetric complications (i.e. preterm birth and low birth weight) (Accortt, Cheadle, & Schetter, 2015; Becker, Weinberger, Chandy, & Schmukler, 2016) and early child development difficulties, including emotional problems, insecure attachment, and low levels of cognitive development (Herba, Glover, Ramchandani, & Rondon, 2016; Pearlstein, 2015).

Despite the current knowledge on psychiatric disorders during pregnancy, less is known about the true impact of a global pandemic like COVID-19 on the mental health of pregnant women. In the present study, we aimed to determine the incidence of depression, anxiety, and stress among a Portuguese sample of pregnant women, during the national state of emergency lockdown. This study also aimed to obtain a holistic view about the risk factors, as well as the maternal characteristics associated with this phenomenon.

Methods

Study Design and Sample

This study presents data from a cross-sectional study performed among Portuguese pregnant women who completed an online self-report questionnaire between 25th April and 30th April 2020. Eligibility criteria included pregnant women aged more than 18 years, who were living in Portugal, and who agreed to take part on the study after completing an informed consent.

An online questionnaire, stored via Google Forms (Google, 2020), was developed by the research team members, and took approximately 10 minutes to complete. We used a self-explanatory questionnaire which did not depend on additional information or support in order to be completed online (Portuguese and English versions available upon request).

A total of 1750 women participated in the current study. Those who did not fully complete the questionnaire or refused to give consent were automatically excluded. By joining in the completion of the questionnaire, participants understood that all the information obtained would be strictly confidential, with guarantee of anonymity and data protection on future publications on the topic. In the end, participants were given advice to seek medical support if needed and a contact line of our hospital department (including phone number and email) was also provided.

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Hospital Dona Estefania – Centro Hospitalar Universitário de Lisboa Central in Lisbon (reference number: INV80-872/2020).

Study Measures

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale – EPDS: The EPDS is a 10-item self-report questionnaire, extensively used as a screening scale for perinatal depression (Bergink et al., 2011; Cox, Holden, & Sagovsky, 1987). A cut-off of 13 is generally used, with higher scores denoting more symptomatology.

Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale – DASS-21: The DASS-21 is a 21-item self-report questionnaire divided in three subscales of 7-items designed to measure the emotional states of depression, anxiety and stress (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995). The DASS-21 and EPDS were both adapted and validated for Portuguese (Areias, Kumar, Barros, & Figueiredo, 1996; José L. Pais-Ribeiro, 2004).

Sociodemographic characteristics: Data was obtained on age, place of residency, marital status, household, highest qualification, and current employment status.

Pregnancy data: Participants were asked to give information regarding the gestational age, impact of COVID-19 on medical vigilance, and family support.

Medical history: Medically relevant issues were requested, such as past and/or current psychiatric disorders.

Stress factors associated with COVID-19: Pregnant women were asked to rate fear of contamination and/or transmission of the disease, fear of early separation from the baby after birth, and fear of not being permitted to breastfeed due to COVID-19 safety measures.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data analysis was performed using Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) software version 25.0 (IBM, 2017). The significance level chosen corresponds to a p-value of ≤ 0.05. The mean and standard deviation were used to describe quantitative variables. Percentage and proportions were performed to describe the variables and study measures were rearranged into categories.

The association between categorical variables were tested using the Chi-square test or the Fisher’s exact test; comparisons between continuous variables were done using a two-sample t-test or the non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum test (when the data is not normally distributed). By using electronic data capture that required participants to provide responses, there was very little missing data in the analysis variables.

Results

A total of 1750 women participated in the current study. Of these, 52 were excluded since they were not living in Portugal during lockdown. A final sample of 1698 women was obtained. The average age of the participants was 31.89 years (SD 4.334; min. 19 years; max. 49 years). The majority of women had a high school (20.7%) or university educational level (76%). Within the population covered by this study, 90.5% were working before the pandemic. Of those, 46.4% suspended their professional activity, 23.6% were transferred to teleworking and only 3.2% remained at their usual place of work. The current pregnancy was reported to be the first one in 58.4% of our sample.

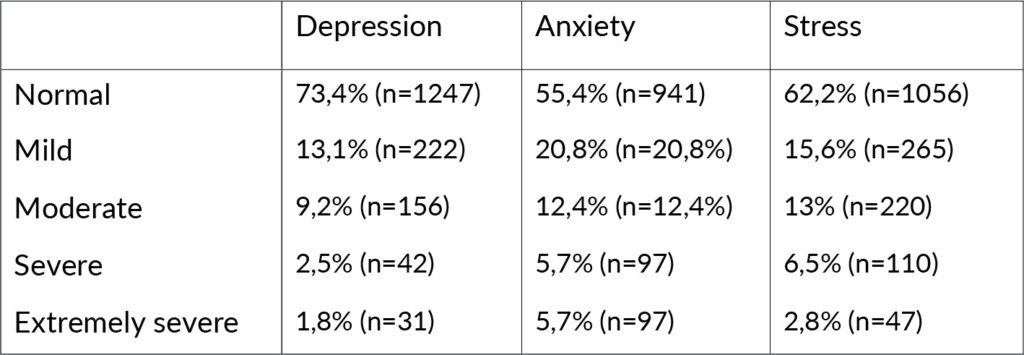

Most women were in the third trimester of pregnancy (61.1%) and only 8.1% were in the first trimester. In 81.2 % the current pregnancy was being supervised by an obstetrician and in 18.2% by the general practitioner. Regarding the psychiatric history, only 6.6% were currently being followed up in psychiatry or psychology consultations and 30.3% reported having been in the past. Of the 63.1% who answered that they had no previous follow up in mental health appointments, 14% said they feel they needed it at that moment. In our sample, 26% of pregnant women reported symptoms of depression (according to both used scales); 45% symptoms of anxiety and 38% symptoms of stress (Table 1).

Table 1. Prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress symptoms reported by DASS 21.

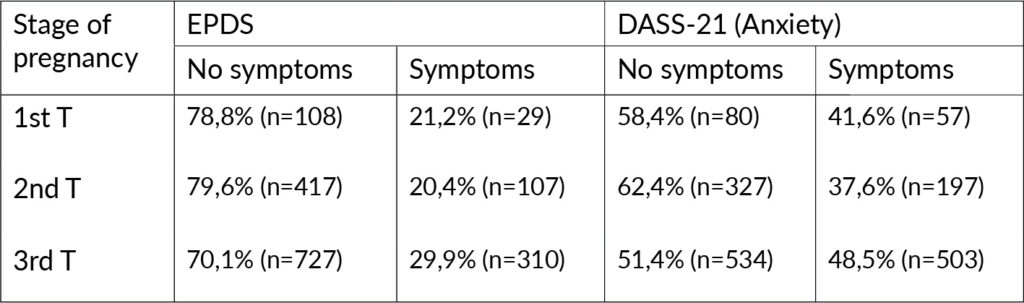

The prevalence of depressive and anxious symptoms was higher in pregnant women in the third trimester (Table 2). Participants were also divided according to the place of residency revealing that higher rates of depression and anxiety symptomatology were encountered in Algarve, Alentejo, Madeira, and Azores Islands regions.

The vast majority of participants (86.4%), reported that the pandemic situation was related to a subjective feeling of higher anxiety and concerns about the current pregnancy. Circa 80% women considered that the current pandemic situation had a negative impact on the surveillance of their pregnancy, mainly due to a postponement of scheduled appointments (41%), impossibility or difficulty in scheduling new appointments (27%), cancellation or postponement of ultrasounds (16%) or, due the impossibility of being accompanied by any family member to medical appointments (72%). Lack of support at this stage of their life was reported by 43% of women.

Due to the current pandemic, 7.4% did the laboratory test to SARS COV 2 and 0.3% (n=5) had been diagnosed as infected with COVID-19. All pregnant women that had been infected had developed only mild symptoms. In our sample, 48.1 % of the pregnant women reported high fear of contracting the virus and 82.3% mentioned they felt afraid of the possibility of passing the infection to the newborn. Other concerns were related to the possible absence of a partner or another family member during labour or postpartum (moderate to high concern in 92.8%), impossibility of skin-to-skin contact (moderate to high concern in 93.8%), initial seclusion of the newborn (moderate to high concern in 93.4%) and, possible implications in breastfeeding (moderate to high concern in 88.8%).

Table 2. Prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms by stage of pregnancy.

Discussion

This cross-sectional study revealed a significant increase in depression, anxiety, and stress-associated symptoms, presented by Portuguese pregnant women during the national state of emergency lockdown. A large group of 1698 participants from the general population in Portugal were assessed by the EPDS and DASS-21. These results contrast with previous international studies that reported lower prevalence rates of depression and anxiety during pregnancy (Howard et al., 2014).

A large majority of the participants reported that the pandemic situation was related to a subjective feeling of higher anxiety and related concerns over the course of pregnancy. In our sample, around half of the pregnant women reported being very much afraid of contracting the virus and more than 80% described has being very much afraid of possibly spread the infection to the newborn. Other concerns were related to the anticipated absence of a companion during labour, impossibility of skin-to-skin contact, initial seclusion of the newborn, and possible negative implications in breastfeeding.

Although the protective measures applied by national health authorities were designed to safeguard mothers and babies from the COVID-19 disease, we argue that they may have led to a negative impact on the mental health of this population. In fact, previous studies established associations between worry, trauma and conflict settings, and mental health issues during pregnancy (Charlson et al., 2019; Erickson, Julian, & Muzik, 2019; Mourady et al., 2017).

According to the place of residency, higher rates of symptomatology were encountered in regions with lower socioeconomic status and fewer mental health resources available in the community.

Other aspects related to the pandemic lockdown such as social distancing and lack of family support, may also have contributed to the escalation of psychiatric symptoms. Similarly, restricted access to mental health services may have been even more intense during the pandemic, limiting early detection and intervention in these pregnant women.

If present in the antenatal period and if not treated, mental disorders (such as depression and anxiety) tend to persist during postpartum and may affect both the mother and the development of the infant (Grace, Evindar, & Stewart, 2003; Herba, 2014). These results emphasise the need for:

1. More extensive antenatal screening in this population.

2. The importance of implementing additional mental health resources in the community, and

3. Rapid referral to specialized units (when indicated).

Participants were divided in three groups according to their stage of pregnancy with higher prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms found during the last trimester. This finding is in line with previous literature reports (Biaggi, Conroy, Pawlby, & Pariante, 2016; Marchesi, Bertoni, & Maggini, 2009). During this stage, pregnant women normally experience fear and concerns regarding child birth and tend to request the presence of a close companion during labour with a positive impact on their psychological well-being (Ip, 2000). Since this possibility was initially not allowed by the health authorities, we argued that these circumstances also contributed to these findings.

A strong feature of this study is that the EPDS and DASS-21 are self-completed screening tools that are well validated for Portuguese, making them suitable for use during pregnancy in our population. Despite the fact that these questionnaires do not make a clinical diagnosis, they do investigate a number of symptoms experienced by each participant, providing more comparable results. Other strengths of this study are the large sample size and information on many maternal characteristics throughout pregnancy.

A limitation may be the fact that it was limited in time and most participants were from Greater Lisbon area, limiting the generalization of our findings. Finally, response bias may exist if the nonrespondents were either too depressed or anxious to respond or, not at all interested in this survey due to the lack of symptomatology. These factors should be taken in consideration by future studies.

The main results of this study were initially disclosed in several Portuguese media platforms (i.e. television, radio, newspapers), right after the state of emergency lockdown. Given the widespread access to this information, we believe that our work contributed to a significant change in the national paradigm regarding safety control measures for COVID-19 in pregnancy. In fact, the following official guidelines conducted by national authorities started to focus on the importance of periodic mental health assessments as part of pregnancy surveillance routine, as well as the mandatory presence of a companion during delivery, when indicated.

In order to better understand the true impact of these measures in this population, we are currently conducting a study focused on COVID-19 related effects during the postpartum period. With this study, we strongly believe that mental health awareness in our country was enhanced, providing useful frameworks for decision-makers and also reducing social stigma and discrimination around mental illness.

Conclusion

A cross sectional study was conducted to evaluate the presence of depression, anxiety and stress symptoms in Portuguese pregnant women during the pandemic lockdown. We found a significant increased rate of symptomatology in all stages of pregnancy with a reported subjective feeling of psychiatric symptoms due to COVID-19 and related concerns. The current analysis does not provide definite diagnoses but these results should not discourage the implementation of additional mental health resources specially focused on pregnancy, in order to help the mothers and the future of their babies.

Conflicts of Interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest with regard to the current work.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgement

We thank to Centro de Estudos do Bebé e da Criança (CEBC) of Centro Hospitalar Universitário de Lisboa Central (CHULC) for their support.

References

Accortt, E.E., Cheadle, A.C.D., & Schetter, C.D. (2015). Prenatal Depression and Adverse Birth Outcomes: An Updated Systematic Review. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 19(6), 1306-1337.

Areias, M.E.G., Kumar, R., Barros, H., & Figueiredo, E. (1996). Comparative incidence of depression in women and men, during pregnancy and after childbirth validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in Portuguese mothers. British Journal of Psychiatry, 169(1), 30-35.

Becker, M., Weinberger, T., Chandy, A., & Schmukler, S. (2016). Depression During Pregnancy and Postpartum. Current Psychiatry Reports, 18(3).

Bergink, V., Kooistra, L., Lambregtse-van den Berg, M.P., Wijnen, H., Bunevicius, R., van Baar, A., et al. (2011). Validation of the Edinburgh Depression Scale during pregnancy. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 70(4), 385-389.

Biaggi, A., Conroy, S., Pawlby, S., & Pariante, C.M. (2016). Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 191, 62-77.

CDC. (2020). How to Protect Yourself & Others. Retrieved 29 September, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html

Charlson, F., van Ommeren, M., Flaxman, A., Cornett, J., Whiteford, H., & Saxena, S. (2019). New WHO prevalence estimates of mental disorders in conflict settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet, 394(10194), 240-248.

Cox, J.L., Holden, J.M., & Sagovsky, R. (1987). Detection of postnatal depression – development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. British Journal of Psychiatry, 150, 782-786.

Dennis, C.L., Falah-Hassani, K., & Shiri, R. (2017). Prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety: systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 210(5), 315-323.

DGS. (2020). Orientação sobre gravidez e parto, from https://covid19.min-saude.pt/dgs-publica-orientacao-sobre-gravidez-e-parto/

Erickson, N., Julian, M., & Muzik, M. (2019). Perinatal depression, PTSD, and trauma: Impact on mother-infant attachment and interventions to mitigate the transmission of risk. International Review of Psychiatry, 31(3), 245-263.

Google. (2020). Google Forms, Google Docs Editors software. Mountain View, CA:Google LLC

Grace, S.L., Evindar, A., & Stewart, D.E. (2003). The effect of postpartum depression on child cognitive development and behavior: a review and critical analysis of the literature. Arch Womens Ment Health, 6(4), 263-274.

Herba, C.M. (2014). Maternal depression and child behavioural outcomes. Lancet Psychiatry, 1(6), 408-409.

Herba, C.M., Glover, V., Ramchandani, P.G., & Rondon, M.B. (2016). Maternal depression and mental health in early childhood: an examination of underlying mechanisms in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Psychiatry, 3(10), 983-992.

Howard, L.M., Molyneaux, E., Dennis, C.L., Rochat, T., Stein, A., & Milgrom, J. (2014). Non-psychotic mental disorders in the perinatal period. Lancet, 384(9956), 1775-1788.

Howard, L.M., Ryan, E.G., Trevillion, K., Anderson, F., Bick, D., Bye, A., et al. (2018). Accuracy of the Whooley questions and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in identifying depression and other mental disorders in early pregnancy. British Journal of Psychiatry, 212(1), 50-56.

IBM. (2017). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 25.0). Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

Ip, W.Y. (2000). Relationships between partner’s support during labour and maternal outcomes. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 9(2), 265-272.

José L. Pais-Ribeiro, A.H., Isabel Leal. (2004). ontribuição para o Estudo da Adaptação Portuguesa das Escalas de Ansiedade, Depressão e Stress (EADS) de 21 itens de Lovibond e Lovibond. Psic., Saúde & Doenças, 5, 10.

Kendig, S., Keats, J.P., Hoffman, M.C., Kay, L.B., Miller, E.S., Simas, T.A.M., et al. (2017). Consensus Bundle on Maternal Mental Health Perinatal Depression and Anxiety. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 129(3), 422-430.

Lovibond, P.F., & Lovibond, S.H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states – comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (dass) with the beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335-343.

Marchesi, C., Bertoni, S., & Maggini, C. (2009). Major and Minor Depression in Pregnancy. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 113(6), 1292-1298.

Mourady, D., Richa, S., Karam, R., Papazian, T., Hajj Moussa, F., El Osta, N., et al. (2017). Associations between quality of life, physical activity, worry, depression and insomnia: A cross-sectional designed study in healthy pregnant women. PLoS One, 12(5), e0178181.

Pearlstein, T. (2015). Depression during Pregnancy. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 29(5), 754-764.

WHO. (2020). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Retrieved 29 September, 2020, from https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019

Woody, C.A., Ferrari, A.J., Siskind, D.J., Whiteford, H.A., & Harris, M.G. (2017). A systematic review and meta-regression of the prevalence and incidence of perinatal depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 219, 86-92.

Authors

Rafael Figueiredo, Pedro,

Hospital Garcia de Orta, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Almada, Portugal

Mesquita Reis, Joana,

Centro Hospitalar Universitário de Lisboa Central, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Lisbon, Portugal

Centro Hospitalar Universitário de Lisboa Central, Centro de Estudos do Bebé e da Criança, Lisbon, Portugal

Padez Vieira, Francisca,

Centro Hospitalar Universitário de Lisboa Central, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Lisbon, Portugal

Lopes, Patrícia,

Centro Hospitalar Universitário de Lisboa Central, Centro de Estudos do Bebé e da Criança, Lisbon, Portugal

João Nascimento, Maria,

Centro Hospitalar Universitário de Lisboa Central, Centro de Estudos do Bebé e da Criança, Lisbon, Portugal

Marques, Cristina,

Centro Hospitalar Universitário de Lisboa Central, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Lisbon, Portugal

Caldeira da Silva, Pedro,

Centro Hospitalar Universitário de Lisboa Central, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Lisbon, Portugal

Centro Hospitalar Universitário de Lisboa Central, Centro de Estudos do Bebé e da Criança, Lisbon, Portugal

Corresponding Author: Pedro Rafael Figueiredo, Rua Luís António Verney 35, 2800-025 Almada, Portugal. Email Address: pedro.rafael.figueiredo@hgo.min-saude.pt