Introduction

This article reports the accounts of five early childhood practitioners who remained in their childcare facilities throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Their respective centers remained open for the young children of essential workers. These practitioners remained committed to young children and their families during the pandemic. The practitioners provide a perspective necessary for contributing to the development of future early childhood methods needed during a crisis or traumatic episodes.

Background

Approximately 76% of children ages three and four in the United States receive education and care from someone other than a parent, for example, “… the majority attend a center-based program defined as preschool, childcare, or Head Start” (National Institute for Early Education Research). However, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the disease quickly spread and within weeks, forced the closures of businesses, places of worship, and schools; everything except locations deemed essential and necessary for basic survival. Most childcare facilities closed for several months, leaving many parents and/or primary caregivers with few options for their children (The Center for Disease Control and Prevention).

As a global community, we collectively praised essential hospital workers, grocery store employees, transportation workers, and emergency responders during the pandemic. However, the stories of another group of essential workers have not been as widely shared. Namely, the experiences of early childhood practitioners in childcare facilities that remained open throughout the quarantine period. Early childhood practitioners are essential to the continued growth and development of children and they also support the families of young children (Kleyn & Shaughnessy, 2012). Research suggests that when children receive quality early childcare learning experiences, this contributes toward more success in cognitive and social-emotional development (Espinosa, 2002).

When COVID-19 broke out, several employees in businesses, places of worship, pharmacies, and all emergency response systems needed childcare, as most of their children ordinarily would be in Daycare, Head Start, centers, and or preschools. However, to prevent the further outbreak and spread of COVID-19, most childcare agencies closed indefinitely or until their leadership received guidelines for re-opening. Many sites closed for at least 12 weeks. This left few options for children of essential workers during the pandemic with most of them reporting that they were without childcare (Bipartisan Policy Center, 2020).

Recognizing the need for quality childcare, some private early childhood sites remained open with permission from state agencies, and some were encouraged by state government leaders to support those that could not work from home. As a result of the commitment by essential early childhood faculty and staff, willing to provide support for families during the pandemic, many children of essential workers were able to remain in their childcare facilities, but not without their own challenges.

The early childhood practitioners who shared their workplace experiences

All five practitioners are undergraduate students in a public university in the northeast USA majoring in Early Childhood Studies-Infant/Toddler Mental Health. The author served as their faculty advisor during the COVID-19 pandemic and provided support and development as needed. Each of the five practitioners participated in one-on-one, virtual, semi-structured interviews with the author, allowing for data collection to occur in alignment with the newly revised health and safety protocols.

All of the practitioners are enrolled in a program to become credentialed early childhood professionals to support families of young children and provide opportunities for high-quality infant/toddler and early childhood mental health development. These practitioners also need to be recognized as essential for maintaining their classroom positions to ensure children of essential workers continue receiving quality childcare while their parents served their communities.

The Voices of Early Childhood Practitioners

Note: All names used in this paper are pseudonyms.

Sarah

Sarah is in her fifth year working at an early childhood center not far from her home. She is the headteacher for the infant room and has several schedules to maintain throughout the day for each child. Before the global pandemic of COVID-19, Sarah’s site enrolled at least 60 young children this year, but during the pandemic, enrollment dropped by over 35%. One powerful illustration that Sarah shared, emphasizes the need to find innovative methods for supporting families during a crisis. It is important to understand that traditional approaches will not always apply to every scenario to provide quality care to young children and their families.

I remember a parent breaking down in tears with me because her daughter always wanted to hug her as soon as she would pick her up because in the beginning of the pandemic, we had to decrease hugs to our kids. It was sad because her mom works in a hospital and cannot give hugs right after work either, so that hurt too. Her mom told us that she always wants to leave work immediately and fears that changing her clothes at work won’t keep her from being clean, I guess. She still must walk through the hospital, so she has little choice. Because of her dilemma, our center started working on ways to help her, so we decided to let her leave a change of clothes at our center every day and we let her come in a few minutes before pick up to change in our staff restroom and then go back outside to wait for her daughter and now she gets to hug her mom as soon as we bring her out for dismissal. (Sarah)

Josephina

Josephina is in her ninth year as an early childhood practitioner and seventh year at her current location. She is the lead teacher in the classroom for the two-year-olds and a leader among the faculty at her site. Josephina voiced her desire to do more than just listen to families but to work with her colleagues to develop solutions that could help relieve the anxiety many families face during a crisis.

I had this overwhelming moment when I was able to almost interpret what this parent needed. I noticed every day at 1 pm, she’d call us frantic, checking to make sure her son wasn’t spiking a fever. One day, when she came to pick him up, I just asked her; why at that moment each day did she call. I found out her shift in the Covid unit at the hospital starts at 12:30 and after 30 minutes there, she would just get scared and want to check on him. She was scared about bringing it [COVID-19] home to him; especially because she was on the front lines. That’s when I asked my director could we increase our daily communication to parents to include midday reports … and we did. (Josephina)

Suzanne

Suzanne is in her third year as an assistant teacher but also works as a headteacher for infants and three-year-old children. She is also responsible for closing the center every night. Although enrollment experienced a 30% decline during the pandemic, this site was the only one of the five that allowed children of non-essential workers to remain if they were previously enrolled.

Suzanne described several moments when she felt anxious about her ability to provide the usual high-level of care for children and families. She suggested that other practitioners tried to remain positive during challenging situations and described moments that helped her overcome the personal stress of supporting families during the pandemic.

We recorded temperatures throughout the day in case a child spiked after arrival. When it got really bad, we sent instant messages to families or babysitters to tell them their child’s temperature, even if it was normal. Parents really appreciated the extra level of communication; my director wants to keep this and other new methods even when the pandemic is over. These types of changes helped relieve my own stress and anxiety. I needed these kinds of moments. I was getting so stressed out and needed consistency and ways to calm parents down, which calmed me down too. (Suzanne)

Marie

Marie is a first-year assistant teacher for the “woddlers” room (children starting to walk and toddlers). Before the pandemic, Marie’s location enrolled 60 children; but during the pandemic, enrollment dropped to only 20 children of essential workers. Marie was the only first-year practitioner interviewed, and she revealed that she was anxious and concerned about several issues, but primarily her ability to provide quality care during a pandemic.

I had to remind myself constantly to take it one day at a time. I had to give myself grace in everything and say, ‘this is my first year and there’s a pandemic’. But even if it wasn’t a pandemic, I need to just take it step by step. I think a lot of teachers make this mistake and that’s why there is so much teacher burnout. I wish we had more advice on how to deal with the stress so that we can be there for our kids when they need us. (Marie)

Florenze

Florenze is in her 11th year at her childcare site and received a promotion to headteacher four years ago. Prior to the pandemic, there were 75 children enrolled. The enrollment dropped to about 20 during quarantine and only children of essential workers were permitted.

As the practitioner with the most experience, Florenze highlighted the concept of focusing on the verbal and non-verbal cues that families and their children express. She shared examples of her own anxiety about missing such cues but learned how to understand the signals and was able to provide more support for families.

I learned quickly that I needed to listen more intently to the needs of the parents since this was a traumatizing event for most of them. I paid closer attention and observed some of the children’s behaviors changing. That’s when I started to put it all together. I learned so much but one of the most important lessons is to listen closely and watch carefully so that you can support your families during traumatizing events and any challenges they’re facing. (Florenze)

All of these experiences shared by these early childhood practitioners offer valuable glimpses into their classrooms and given the unprecedented nature of the pandemic, it is critical to listen to these voices.

Caring for Kids During COVID-19: What Common Practices Changed?

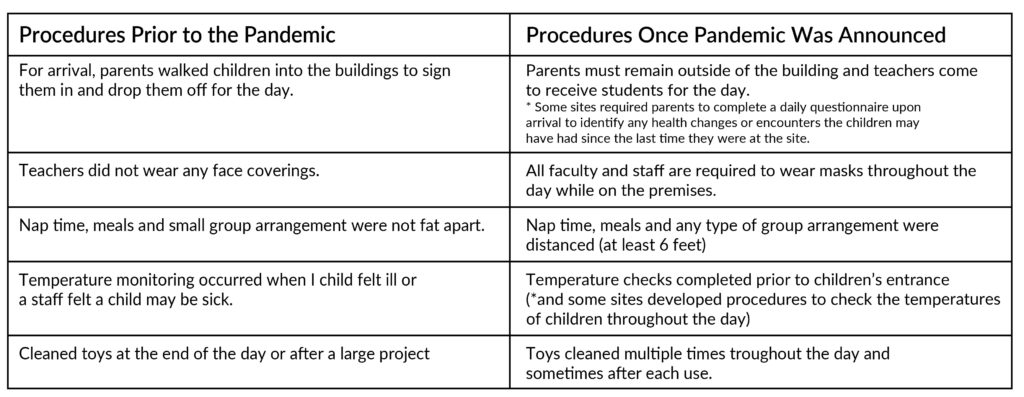

While administrators, faculty, and staff at early childhood sites tried to maintain normalcy during the quarantine, all five practitioners shared similar experiences with changes such as adjusted child drop-off procedures and enhanced cleaning protocols. All sites implemented new methods to keep classrooms safe throughout the global pandemic. Table 1 shows the procedure changes that most early childhood sites implemented because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 1. Adjustments to Early Childhood Classroom Procedures Due to COVID-19 Pandemic.

Several common procedural adjustments were implemented as site directors and instructional leaders learned more about social distance practices for ensuring a safe environment and many will maintain these changes post-pandemic.

Emerging Concepts from Early Childhood Practitioners’ Stories

The experiences of the five early childhood practitioners provide an opportunity to understand the concepts they communicated and consider the possible impact on future early childhood educational practices. Across the five interviews, three main themes emerged from the practitioners’ account of their experiences:

- Support for families.

- The need for consistent clear communication; and

- Caring for early childhood practitioners.

These themes are identified as a starting point for understanding how to support young children and families when facing a crisis such as the COVID-19, that impacts everyone.

1. Support for Families

The most common theme shared was the need to support families throughout the pandemic and to consider how childcare providers can help families when dealing with critical conditions. Recognizing that a family’s challenging situation can impact children’s social/emotional development and mental health (Sameroff & Fiese, 2000), it became imperative for early childhood practitioners to become even more observant. Especially when looking for signs of stress from children and families and providing support with an enhanced level of patience.

One example included children’s reactions to staff members at all sites wearing masks throughout the day and recognizing how stressful this became for families. A primary childcare recommendation for sites shared by the Connecticut Office of Early Childhood (2020) was the need for all employees to wear masks while in their sites at all times.

All five practitioners shared that most children at their sites were initially afraid when introduced to their teachers in masks. Children that were ordinarily comfortable at school became visibly tense, scared, and many cried when they transitioned from their parent to a person in a mask. The children found it difficult to recognize the staff member. While it was initially a stressful situation, as one practitioner said,

…it just took more patience for everyone involved to support the children through the transition. (Marie)

Other practitioners shared games they created to help children and their family transition:

I decided to make up a peek-a-boo game for the kids when I was wearing my mask and that made it so much easier. (Florenze)

Recognizing that masks may become a permanent fixture in learning facilities, this experience allowed practitioners to plan methods to help children and families adjust to this “new normal.”

2. The Need for Consistent Clear Communication

The need to communicate effectively and swiftly with families was another common theme shared. There were rapid, daily, and sometimes hourly adjustments that occurred during the pandemic, and it became necessary to learn and implement alternative methods for communicating with families consistently.

The five practitioners all described the need to revise daily protocols and logs to provide families with the latest information to ensure the safety of each child. Information that many sites typically communicated to families at the end of the day during pick up, was now shared throughout the day.

While research suggests that positive teacher-child relationships in early childhood can enhance a child’s academic and peer success in the future (Bakken, Brown & Downing, 2017), this experience highlights the need for families to have successful relationships with their child’s teachers as well. It presents the need to develop trusting connections between families and faculty that could further support children’s development. Consistent communication helps to build those trusting relationships.

3. Caring for the Caregivers

Given the pressure to be available every day for children and families during unpredictable circumstances with little guidance or precedent on how to proceed, all five practitioners recognized that they could experience their own level of stress that would impact their ability to provide quality care.

Often educators are taught to complete lesson plans in advance or have three weeks of activities planned ahead (Cicek & Tok, 2014). However, in the middle of a crisis, there is a need to abandon traditional philosophies and routines to maintain your own physical and mental capacity.

Most of the practitioners shared that receiving protocols or directives from administrators and/or supervisors, that encourage practices on how they might relieve their own stress, helped them enhance their abilities to provide positive care for children while supporting their families through a crisis.

Conclusions

The shared themes highlighted in this article:

- Illustrate that families and their young children have needs during a crisis and early childhood professionals need to be equipped with the knowledge to support families during traumatizing experiences.

- Emphasize the need for further professional development for early childhood faculty and staff, to introduce as part of their new long-term plans, ways for maintaining a safe learning environment for young children.

- The COVID-19 pandemic exposed the dire need to maintain quality early childcare learning environments for children and their families consistently throughout the year.

While there were several lessons learned, the primary understanding is the value of early childhood practitioners and how significant their roles are to support the continued development of children and their families.

Government leaders must help to ensure that early childhood practitioners receive the resources needed to be trained in methods for promoting social-emotional development for children but that they also consider offering supportive services to prevent burnout and fatigue during a crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

The world is grateful to all essential workers—first responders, employees in hospitals, grocery stores, transportation workers, and the early childhood faculty and staff in the classrooms that never closed.

References

Bakken, L., Brown, N., & Downing, B. (2017). Early Childhood Education: The Long-Term Benefits, Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 31:2, 255 269, DOI: 10.1080/02568543.2016.1273285

Bipartisan Policy Center (2020). Nationwide Survey: Child Care in the Time of Coronavirus. Retrieved from https://bipartisanpolicy.org/blog/nationwide-survey-child-care-in-the-time-of-coronavirus

Cicek, V., & Tok, H. (2014). Effective use of lesson plans to enhance education in us and Turkish kindergarten thru 12th-grade public school system: a comparative study. International Journal of Teaching and Education, 2(2), 10-20.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2020). Frequently Asked Questions: Basics. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/faq.html#Basics

Connecticut Office of Early Childhood (2020). Guidance for Child Care-Centers and Group Child Care Homes. Retrieved from https://www.ctoec.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/OEC-COVID-19-Guidance-for-Child-Care-Centers-Group-Homes-2020-06-24.pdf

Espinosa, L. M. (2002). High-Quality Preschool: Why We Need It and What it Looks Like [Policy Brief]. New Brunswick, NJ: National Institute for Early Education Research.https://www.readingrockets.org/article/high-quality-preschool-why-we-need-it-and-what-it-looks

Kleyn, K., & Shaughnessy, M. F. (2012). The Importance of Early Childhood Education. In M. Shaughnessy & L Kleyn (Eds.). Handbook of Early Childhood Education (pp.1-7). New York USA: Nova Science Publishers Inc.

Sameroff, A. J., & Fiese, B. H. (2000). Transactional regulation: The developmental ecology of early intervention. In J. P. Shonkoff & S. J. Meisels (Eds.), Handbook of early childhood intervention (pp. 135–159). Cambridge University Press.

Authors

Dr Barriteau Phaire, Candace,

Assistant Professor & Program Coordinator,

Early Childhood, Infant/Toddler Mental Health,

Central Connecticut State University