Background

The consequences of not investing in the mental health needs of children at the earliest stages of life means denying thousands of children the opportunity to reach their life potential as well as accumulating huge financial costs (Segal et al., 2018:172).

Infancy is when children are most vulnerable to psychological harm, but also when they are most malleable to positive intervention (Nix et al., 2016). Studies have consistently shown that infants have a similar prevalence of mental illness as their older peers, with estimates ranging from 10-22% (Egger & Angold, 2006; Wichstrøm et al., 2011; Skovgaard, 2010); yet infants are rarely referred to mental health services in Scotland. For example, in the area studied here, only 0.3% of referrals to child and adolescent mental health services were for under 3’s; amounting to 17 referrals for the 20,700 under 3’s living there (National Records Scotland, 2018).

Early intervention reduces symptoms, reverses negative developmental trajectories, and improves academic/socio-emotional outcomes (Knapp et al., 2007; Wiefel et al., 2005). Infancy is a time of rapid brain development in which interactions with caregivers are crucial and relationship-focused interventions may be helpful (Ilyka et al, 2021). Interventions provided in the early months and years have a greater impact than those aimed at older children (Carter et al., 2004).

In 2019, the Scottish Government committed resources to ‘implement and fund a Scotland wide model of infant mental health provision’ (Scottish Government, 2019). However, various studies report that there is a belief that infants are too young to suffer from mental health issues, and hence are too young to benefit from a service; they also report a parental fear of blame if they were to seek help (Harwood et al., 2009; Nelson & Mann, 2011).

We conducted a systematic literature review (details available on request from the authors) which identified little previous research on barriers or enablers to infant mental health (IMH) service development. In spite of a wealth of IMH literature that supports the case for parent-infant services (Fivaz-Depeursinge & Philipp, 2014; Fraiberg, 1980; Lieberman & van Horn, 2011; McArthur et al., 2021; McHale, 2007; Osofsky & Lieberman, 2011), the writings of Gesell (1941) through to Harwood et al., (2009) indicate two key points: 1. that infant mental health service development has rarely been sustained over time and 2. an ongoing narrative about service development being parent focused and not infant or (parent-infant) relationship focused.

Following the identification of these gaps in the literature, we conducted a qualitative study with the overarching research question:

“Why is it challenging to build IMH services, despite the fact that we know that the baby’s brain is developing so rapidly?”

Methods

Study Design

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Glasgow College of Medical, Veterinary and Life Sciences. The research team was made up of 7 members, including child and adolescent psychiatrists and psychotherapist, a health psychologist, and a medical student. All researchers took part in a recorded interview to examine any preconceptions or potential biases. A semi-structured interviewing format was used, with open questions to allow the interviews to be guided by participants.

Participants

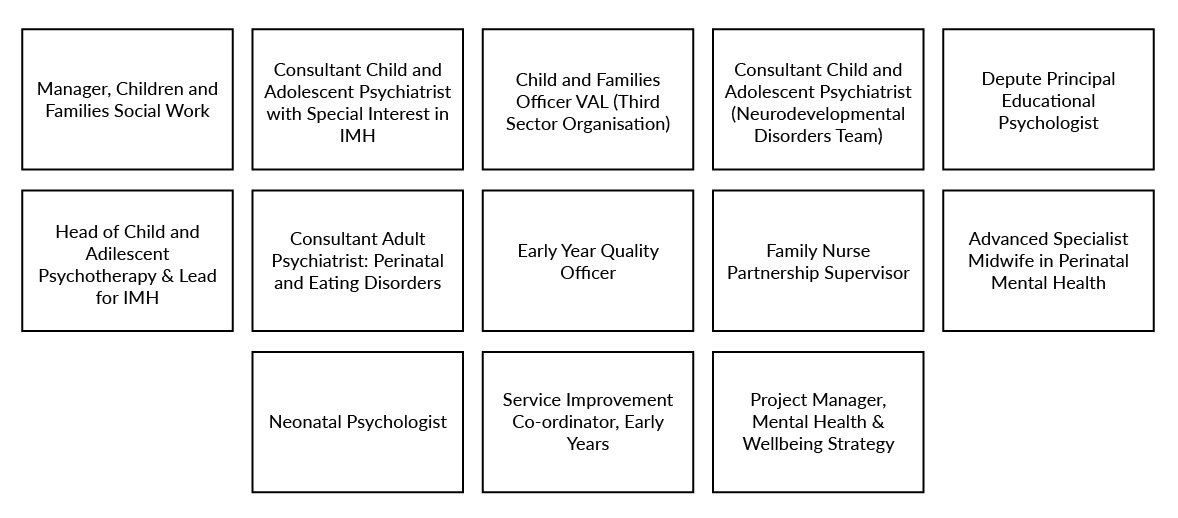

Participants were drawn from a local IMH stakeholders group whose task was to advise on the development of a new IMH service in one area of Scotland. It comprised 31 health, local authority and third sector professionals, and parents/carers. Individuals were purposively sampled from this list by the research team to cover a range of professions (see Figure 1). Thirteen stakeholders were interviewed, and a further three were contacted with no response.

Figure 1. Professional roles of participants in qualitative interviews.

Parents and carers are key stakeholders of IMH services but, for the purposes of this study were not interviewed because the services were not yet up and running at the time the study was conducted. There are plans to explore views of service users after they have had time to experience the new services and it is important that these include wider family members such as grandparents.

Consent and interview process

An information sheet was sent in advance by email and permission for recording was obtained at the beginning of the interview, followed by reading of the consent form.

Each participant was interviewed by a pair of interviewers to minimise bias; one would act as a ‘guider’, inquiring around the topic guide, whilst the other would act as an ‘inquirer’, probing follow-up questions. Each interview lasted approximately one-hour.

The interviews were transcribed verbatim and anonymised to maintain confidentiality. For data protection, each participant was given a study ID number, and a document tracking this system was kept separately.

Analysis

Thematic analysis, according to the methods of Braun and Clarke (2006) was deemed the most appropriate method of analysis to systematically examine the data and interpret meaning.

Phase 1 – Familiarising

6 members of the research team independently read and re-read two transcripts allocated randomly, reflecting, and noting points of interest.

Phase 2 – Generating Initial Ideas

Each researcher independently generated initial codes for these transcripts, shared initial findings, and these were combined into a coding rationale table identifying similarities and differences.

The 3 members who had performed the interviews then followed phases one and two for a further two transcripts, chosen purposefully to contrast with the first two in the hope of generating any remaining themes. Very similar codes were identified; these were compiled into a further coding rationale table.

Phase 3 – Searching for Themes

Each interviewer independently generated preliminary coding frames based on these coding rationale tables, clustering related codes within an overall heading that captured their essence; these were the initial themes.

Phase 4 – Reviewing Themes

The interviewers then discussed the benefits of each independent preliminary coding frame to develop a combined coding frame.

Each of the remaining transcripts were coded independently by one of the interviewers using the agreed coding frame. The interviews with the researchers were also coded to aid reflexivity and identify any further themes that may have impacted data collection/handling.

Phase 5 – Defining and Naming Themes

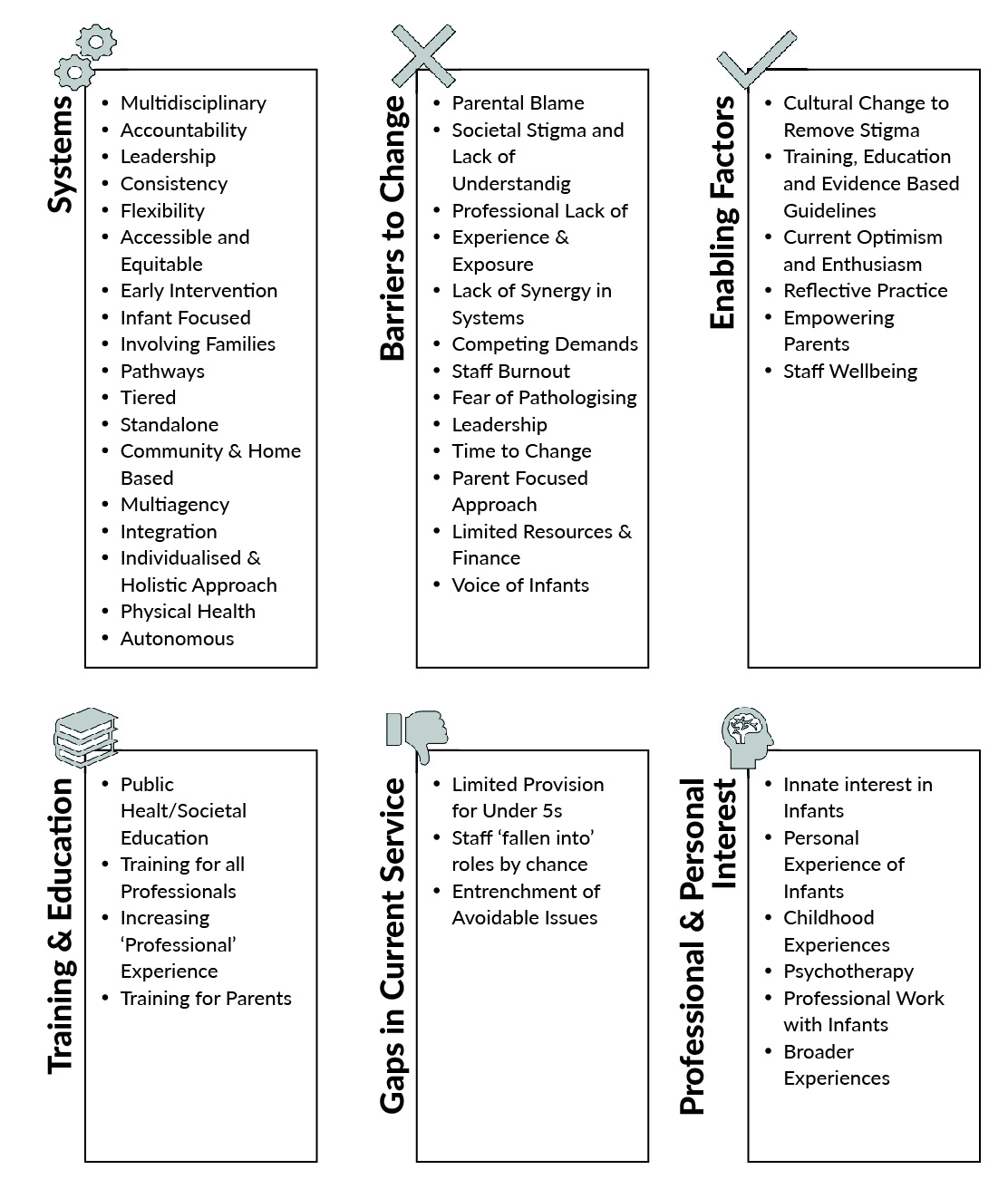

Names of themes, and their sub-themes were discussed and agreed; systems, barriers to change, enabling factors, training and education, gaps in current services, and professional and personal interests. Sub-themes will be further explored in ‘results’ and are displayed in Figure 2.

Results

Six over-arching themes were identified. These are outlined in Figure 2 with their sub-themes. This paper will focus solely on perceived barriers and enablers to Infant Mental Health Service Development in Scotland and will explore each sub-theme identified within these themes, alongside quotes from participants. Other papers will follow as other research questions are addressed.

Figure 2. Overview of thematic analysis themes and sub-themes.

Perceived barriers to Infant Mental Health Service Development

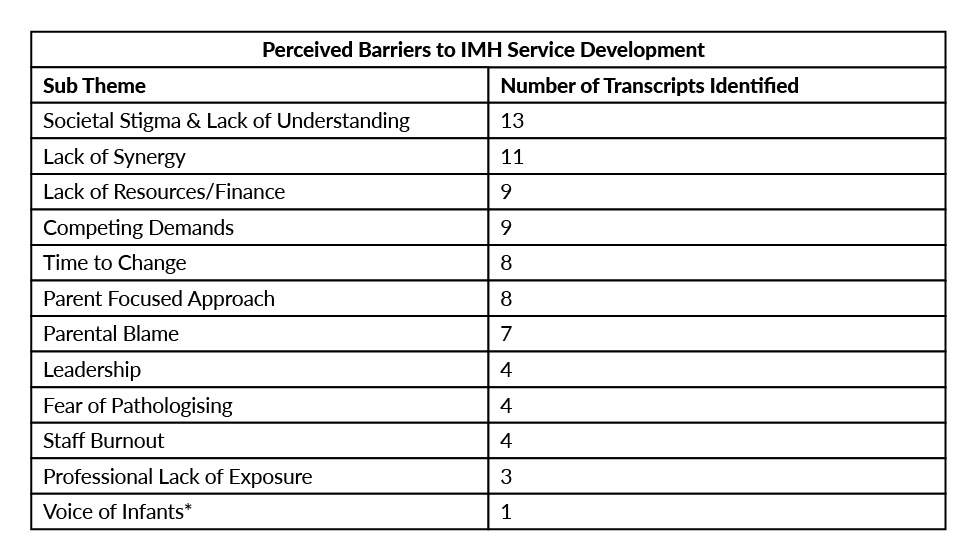

Twelve perceived barriers to the development of an IMH service were identified; these are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Perceived barriers and enabling factors and their endorsement by participants.

* ‘Voice of Infants’ encompasses the idea that infants are unable to formulate words and sentences, and hence their thoughts and concerns often go unheard.

We will now discuss each sub-theme in detail.

- Societal Stigma & Lack of Understanding

This was the only sub-theme amongst ‘Perceived Barriers to Change’ to be mentioned by all participants. Participants perceived a lack of professional understanding – one psychiatrist who had trained elsewhere noted, in contrast with other countries in Europe, IMH is not a familiar concept to UK clinicians, or parents: delaying diagnosis and treatment.

All participants noted stigma surrounding IMH: IMH is not discussed, and the public do not want to accept the idea of ‘babies’ needing a mental health service.

- Lack of Synergy

Participants spoke of a lack of communication between current services, and between professionals and a fear of this continuing. This is exacerbated by different ideologies about what an IMH service should look like.

Participants explained that this fragmentation delays referrals, so professionals are unable to offer infants what they need at the right time. Concern was expressed about how different services would access IMH without effective communication and clear timely pathways; and that those making the referrals to services would not receive the correct training to identify those in need.

- Lack of Resources and Finance

Participants referred to the impact of limited resources and finance resulting in the need for strict criteria, allowing only the most severe cases to be addressed. Some spoke of bouts of funding which supported services to start but not be sustained. There were concerns about a limited number of trained staff.

- Competing Demands

Two participants, each with a service development background, focused on the impact of other health priorities and competition for funding. Participants explained that the current strain in services for older children makes it difficult to prioritise infants.

“If you have concerns about an infant but there’s a child who’s displaying suicidal tendencies then you’re going to respond to that immediate need.” [Local Authority Worker]

- Time to Change

Participants mentioned the time required to improve societal understanding and to implement services; the commitment that this necessitates has previously been absent. Development of services is likely to be a long process, requiring considerable resources and commitment.

- Parent Focused Approach

Another barrier highlighted was that a focus on parents may lead to the infant being forgotten. A neonatal psychologist explained that this is due to the misconception that infants struggle only because their parents are struggling. A midwife explained that recently developed services had repeated this mistake.

- Parental Blame

A culture of parental blame was described which was seen as preventing parents from seeking help and risking losing their engagement. A Project Manager explained that, regrettably, a parent may be apprehensive to raise concerns in the fear that they may be blamed, and that their child may be taken away.

- Leadership

Participants spoke of the detrimental impact of constant changing leadership, and hence varying prioritisation. Historically some leaders have shown interest and progress is made but following leadership change, interest diminishes, and progress is erased.

- Fear of Pathologising

Participants spoke of societal apprehension about turning dysfunction into disorder, and the effect that this has on professional and parental approval of IMH services; likely a repercussion of stigma.

- Staff Burnout

Participants explained that with previous attempts at IMH service development, professionals had difficulties getting referrals accepted, so eventually become exasperated and stopped referring.

- Lack of Professional Exposure

Participants explained that a lack of exposure to infants impedes professionals’ understanding. One psychiatrist was surprised that, unlike in some European countries, it is rare to see under-5s in psychiatry in the UK. Without this exposure, it can be challenging for professionals to develop the necessary skills.

- Voice of Infants

One professional explained that infants’ inability to verbalise their thoughts has prevented them from advocating for themselves, and hence infants being overlooked.

“The origin of the word infant means without speech.” [NHS Clinician]

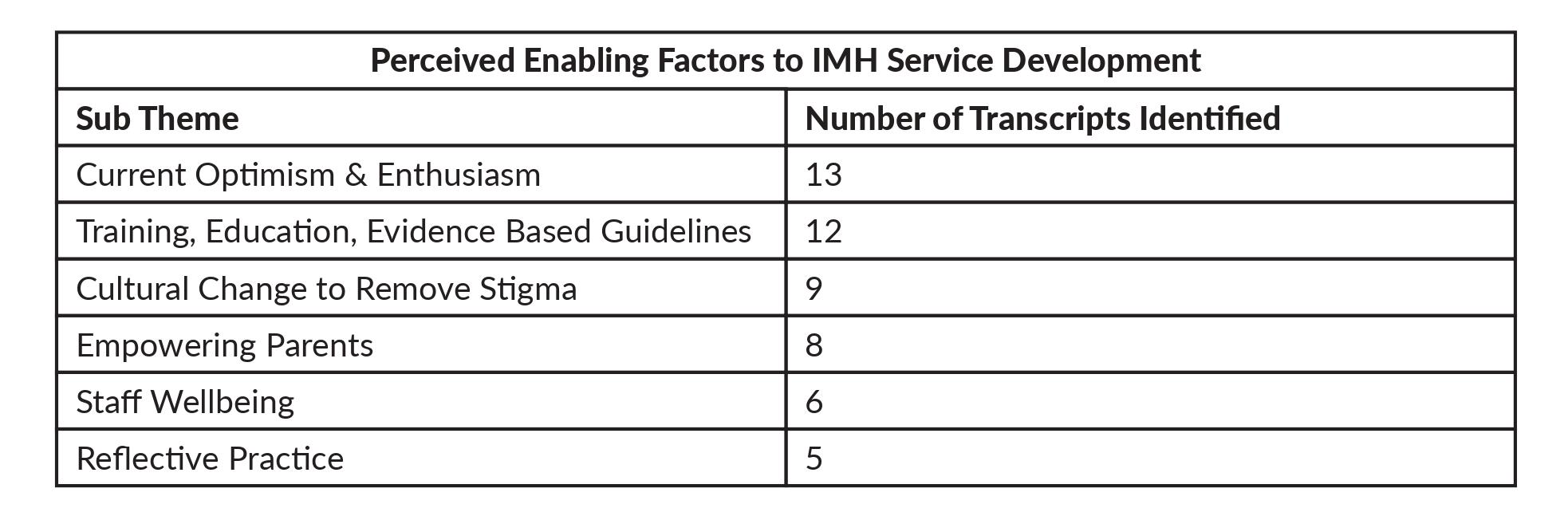

Perceived enablers to Infant Mental Health Service Development

Six perceived ‘Enabling Factors’ were identified, as shown in Table 1. These encompass factors that participants believed would facilitate the development and maintenance of an IMH service.

- Current Optimism & Enthusiasm

All spoke optimistically about current progress in the field; there was excitement and confidence that change was happening. One participant noted the UK’s strength of working well in teams. Participants also referred to the hope that comes from working with infants due to the positive impact of early intervention.

“When you come back to working with infants there is so much hope.” [NHS Clinician]

- Training, Education, Evidence Based Guidelines

A psychiatrist whose European training had encompassed infants felt that their comprehensive understanding of IMH was a result of their exposure to infants during training. Many participants noted the importance of both professional education and public health campaigns. One participant focused on education around infant brain development and a midwife explained that, though midwives know what to do, they do not have the knowledge to understand why. Participants also explained the need to implement ‘indicators’, particularly for less experienced professionals, to help them recognise infants in need and gain confidence doing so.

Some participants explained that evidence demonstrating clinical need was required to access funding, alongside quality assessment to show impact, to maintain funding.

- Cultural Change to Remove Stigma

There was a consensus about the importance of viewing IMH with positivity, tackling stigma, and using of awareness-raising campaigns. A neonatal psychologist spoke of previous normalisation of adult mental health services; the same needs to happen with IMH.

“It is about creating a new culture.” [NHS Clinician]

- Empowering Parents

Participants spoke of the importance of supporting parents to give them the tools to help their child. There was a belief that all parents want the best for their children, but do not necessarily know how to provide that. The importance of working with parents in a non-judgmental, non-threatening way, and ensuring practical supports such as finance and help with access, was emphasised.

- Staff Wellbeing

Participants spoke of the importance of staff wellbeing. One participant spoke of a previous service which had a support team for staff, which in turn boosted morale.

- Reflective Practice

Participants also noted the importance of reflecting on their experiences and responding to the increasing amount of evidence.

Discussion

As found in previous research, as outlined below, we found several perceived barriers to IMH service development. We were also able to identify perceived enablers to IMH service development, something that, to our knowledge, had not previously been identified in the literature.

The perceived barriers identified demonstrate why it is so difficult to implement IMH services. For example, ‘parental blame’ (Harwood et al., 2009; Nelson & Mann, 2011), ‘professional lack of exposure’ (Egger & Angold, 2006; Nelson & Mann, 2011) and ‘voice of infants’ (Egger & Angold, 2006; Hoagwood et al., 2021) have been explored in previous literature, which was congruent with the findings in this research. The concept of ‘voice of infants’ represents the wider thinking of many professionals who are involved in providing direct services to infants; though babies are unable to verbally communicate, they are born ready to relate, with innate behaviours that allow them to communicate (Murray & Andrews, 2005).

By contrast, ‘time to change’, ‘competing demands’, and ‘leadership’ were referenced much more in this study.

Both participants and existing literature emphasised ‘societal stigma’, ‘lack of synergy’, ‘parent-focused approach’ and ‘lack of resources’, indicating the magnitude of their impact.

Many participants discussed parental concerns about being referred to IMH services for fear of judgement, as well as their belief that infants were too young to have mental health problems – findings supported by various studies (Harwood et al., 2009; Nelson & Mann, 2011). One contrasting study found that stigma had ‘minimal salience’, with over 74% of mothers not reporting it as a problem (Frankel et al., 2020). However, that study was based in the USA, where IMH services are more common, and hence there may be cultural differences in attitudes to IMH. For example, the state of Michigan alone has more IMH services than the whole of the UK (Community Mental Health Infant & Early Childhood Mental Health Services in Michigan, 2022).

Another study explained that stigma causes professionals to minimise infants’ problems, searching for protective factors for fear of pathologising them (Harwood et al., 2009).

A ‘lack of synergy’ was confirmed by international literature, indicating that fragmentation is a global problem. A parent-focused (as opposed to infant-focused) approach is also apparent worldwide. Even if the therapeutic task is to address the relationship, attention is often exclusively on the adults in the room. This has been commented on by Beebe (2005):

‘Even in current approaches to mother-infant treatment, the infant is in danger of being the “forgotten patient”’.

Two previous evidence syntheses (Smith et al., 2019; Webb et al., 2021) identified very similar barriers in perinatal mental health, suggesting that both perinatal and infant mental health services experience the same barriers, which may perpetuate the challenges for service development. Unsurprisingly, the barrier highlighted most often in each of these papers was stigma.

Previous literature has identified similar barriers to those evidenced in this study, though this is the first to our knowledge to directly identify factors to combat these barriers and facilitate effective service development.

As stated previously, perceived ‘Enabling Factors,’ to our knowledge, have not been clearly identified in the IMH literature. This could be because the evidence is dispersed and hence not easily identified.

The enabling factors elicited here reflect the perceptions of a group of stakeholders actively engaged in the task of building an infant mental system in their part of Scotland. They encompass their attitudes, values, and beliefs, and they also make practical suggestions about what supports they believe will ensure success. Their optimism, enthusiasm, and positivity may be related to the very fact that resources have been made available to develop an area of work which they value. Their narratives show that they understand why addressing infant wellbeing and relationships during pregnancy and the early years is important, but they are challenged by an awareness that many professionals and parents find this difficult to understand. Nonetheless, they value collaborative working and seek to empower parents and carers, and also tackle the wider stigma which prevents many people from accepting that infants have a mental life and experience not only emotional distress, but also disturbance and disorder. They suggest that both professional and public education are important in this regard.

Their observations about the importance of attending to staff wellbeing, and allowing time for reflective practice, may relate to the emotional impact of working in this area. When babies, for whatever reason, are not part of a close attuned relationship with their primary caregiver, their development is impaired, they experience distress and they are more likely to be abused or neglected (Zeifman & St. James-Robert, 2017). Acknowledging the toll that this takes on clinicians and thinking positively about how to address this can be seen as a positive step to ensuring services succeed.

Reflective practice can also be seen as an enabling factor in the context of the need in this specialist area to take account of the inherent complexity of our models of understanding which integrate the neurobiological with the psychosocial. The dynamics of the baby’s life and relationships are often reflected in the systems around them and taking time to consider these and the feelings they stir up is more likely to lead to a successful outcome.

Attending to the perceived barriers and enabling factors which underpin infant mental health service development is likely to be important in ensuring that these services are created in a sustainable way. This study contributes towards further highlighting and understanding these factors.

Limitations

There was a gender imbalance in this research: 12 of the 13 participants were female.

The use of a pre-existing stakeholder group means that these participants will not be representative of all professionals or the general public, as they are more engaged in IMH.

All participants were White; reflecting the population of the area, where the last census recorded 98.1% as White (Office for National Statistics, 2016). The views of parents and carers have not been included but will be explored in future studies.

Reflexivity

Six of the seven researchers were female and most had a clinical background; all had a personal interest in IMH, as evidenced in the researcher interviews. The researchers’ professional status may have contributed to the level of trust engendered at interview allowing some participants to feel comfortable, though others may have felt intimidated.

Strengths

The participants interviewed had a diverse range of professional and personal backgrounds. The majority had broad training experiences, with many previously working in different professions and some working split-roles, resulting in extensive knowledge and experience from the 13 participants.

Conclusion

The perceived barriers identified in this research reflect what is known in the global literature, with stigma always at the forefront. Without a change in this perception, it will remain challenging to build services, even if all other barriers are removed. The perceived enabling factors identified in this study will contribute towards the overarching goal to be better at identifying and understanding how to implement IMH services. All healthcare professionals should have a basic understanding of IMH, through training and education. A public health initiative to normalise the term ‘IMH’, combat the stigma surrounding it, and increase awareness is imperative. Whilst services must focus on infants and their relationships, it is also important that parents and carers are supported.

Though this research is specific to one area, it is likely that these perceived barriers are not, and hence it is important to build an evidence base for these barriers, and enabling factors both in Scotland, and worldwide. Historically, IMH service development has not been sustained; initiatives have come and gone. It is essential that this time, IMH services are developed and maintained, in Scotland and world-wide.

References

Beebe, B. (2005). Mother-infant research informs mother-infant treatment. The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 60 (1), 7–46.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Carter, A. S., Briggs-Gowan, M. J., & Davis, N. O. (2004). Assessment of young children’s social-emotional development and psychopathology: Recent advances and recommendations for practice. In Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines (Vol. 45, Issue 1, pp. 109–134). https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0021-9630.2003.00316.x

Community Mental Health Infant & Early Childhood Mental Health Services in Michigan. (2022, March 13). Michigan Association for Infant Mental Health. https://mi-aimh.org/tools/imh-services-in-your-area/

Egger, H. L., & Angold, A. (2006). Common emotional and behavioral disorders in preschool children: Presentation, nosology, and epidemiology. In Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines (Vol. 47, Issues 3–4, pp. 313–337). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01618.x

Fivaz-Depeursinge, E., & Philipp, D. A. (2014). The Baby and the Couple: understanding and treating young families (1st ed.). East Sussex: Routledge.

Fraiberg, S. (1980). Introduction. In Fraiberg, S. (ed.) Clinical Studies in Infant Mental Health: The First Year of Life. London: Tavistock Publications.

Frankel, K., Harrison, J., & Njoroge, W. (2020). Psychiatric Assessment of the Very Young Child in the Clinic. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(10), 344–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2020.07.844

Gesell, A. (1941). The Protection of Early Mental Growth: Some Social Implications in the Present Crisis. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 11(3), 498–502. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.1941.tb05833.x

Harwood, M. D., O’Brien, K. A., Carter, C. G., & Eyberg, S. M. (2009). Mental health services for preschool children in primary care: A survey of maternal attitudes and beliefs. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 34(7), 760–768. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsn128

Hoagwood, K. E., Kelleher, K., Counts, N. Z., Brundage, S., & Peth-Pierce, R. (2021). Preventing Risk and Promoting Young Children’s Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Health in State Mental Health Systems. Psychiatric Services, 72(3), 311–316. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.202000147

Ilyka, D., Johnson, M. H. & Lloyd-Fox, S. (2021). Infant social interaction and brain development: a systematic review. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Review, 130, 448-469,

Knapp, P. K., Ammen, S., Arstein-Kerslake, C., Poulsen, M. K., & Mastergeorge, A. (2007). Feasibility of expanding services for very young children in the public mental health setting. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(2), 152–161. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000246058.68544.35

Lieberman, A., & van Horn, P. (2011). Psychotherapy with Infants and Young Children: Repairing the Effects of Stress and Trauma on Early Attachment (1st ed.). New York: The Guilford Press.

McArthur, B. A., Racine, N., McDonald, S., Tough, S., & Madigan, S. (2021). Child and family factors associated with child mental health and well-being during COVID-19. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01849-9

McHale, J. P. (2007). When infants grow up in multiperson relationship systems. Infant Mental Health Journal, 28(4). https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.20142

Murray, L., & Andrews, L. (2005). The Social Baby: Understanding Babies’ Communication from Birth (1st ed.). Richmond: CP Publishing.

National Records Scotland. (2018). Scotland’s Population 2018 – The Registrar General’s Annual Review of Demographic Trends.

Nelson, F., & Mann, T. (2011). Opportunities in public policy to support infant and early childhood mental health: The role of psychologists and policymakers. American Psychologist, 66(2), 129–139. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021314

Nix, R. L., Bierman, K. L., Heinrichs, B. S., Gest, S. D., Welsh, J. A., & Domitrovich, C. E. (2016). The randomized controlled trial of Head Start REDI: Sustained effects on developmental trajectories of social-emotional functioning. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84(4), 310–322. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039937

Office for National Statistics. (2016). 2011 Census aggregate data. UK Data Service. National Records of Scotland; Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (2016).

Osofsky, J. D., & Lieberman, A. F. (2011). A call for integrating a mental health perspective into systems of care for abused and neglected infants and young children. American Psychologist, 66(2). https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021630

Segal, L., Guy, S., & Furber, G. (2018). What is the current level of mental health service delivery and expenditure on infants, children, adolescents, and young people in Australia? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 52(2), 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867417717796

Skovgaard, A. M. (2010). Mental health problems and psychopathology in infancy and early childhood. Danish Medical Bulletin, 57(10).

Smith, M. S., Lawrence, V., Sadler, E., & Easter, A. (2019). Barriers to accessing mental health services for women with perinatal mental illness: Systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative studies in the UK. In BMJ Open (Vol. 9, Issue 1). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024803

Webb, R., Uddin, N., Ford, E., Easter, A., Shakespeare, J., Roberts, N., Alderdice, F., Coates, R., Hogg, S., Cheyne, H., Ayers, S., Clark, E., Frame, E., Gilbody, S., Hann, A., McMullen, S., Rosan, C., Salmon, D., Sinesi, A., … Williams, L. R. (2021). Barriers and facilitators to implementing perinatal mental health care in health and social care settings: a systematic review. In The Lancet Psychiatry (Vol. 8, Issue 6). https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30467-3

Wichstrøm, L., Berg-Nielsen, T. S., Angold, A., Egger, H. L., Solheim, E., & Sveen, T. H. (2011). Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in preschoolers. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 53(6), 695–705. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02514.x

Wiefel, A., Wollenweber, S., Oepen, G., Lenz, K., Lehmkuhl, U., & Biringen, Z. (2005). Emotional availability in infant psychiatry. Infant Mental Health Journal, 26(4), 392–403. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.20059

Zeifman, D. M. & St. James –Roberts, I (2017). Parenting the crying infant. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 15, 149-154.

Authors

Weaver, Alicia,

Medical Student,

Institute of Health and Wellbeing, University of Glasgow

Dawson, Andrew,

Professional Lead for Child Psychotherapy, Specialist Children’s Services,

NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde, Glasgow, UK

Murphy, Fionnghuala,

ST6 Specialist Registrar, Specialist Children’s Services,

NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde, Glasgow, UK

Phang, Fifi,

ST5 Specialist Registrar, Specialist Children’s Services,

NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde, Glasgow, UK

Turner, Fiona,

Health Psychologist,

Institute of Health and Wellbeing, University of Glasgow

McFadyen, Anne,

Consultant Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist, NHS Lanarkshire,

Infant Mental Health Lead, PMHNS,

Chair, IMH Implementation and Advisory Group, SG PIMH Programme Board

Minnis, Helen,

Professor of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry,

Institute of Health and Wellbeing, University of Glasgow

Anne McFadyen and Helen Minnis are joint senior authors

Alicia Weaver is the corresponding author