Introduction

Reflective Supervision/Consultation (RSC) is regarded as one of the pillars of Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health (IECMH) services from promotion through clinical work (Shea et al., 2016). Recently there has been increased interest in RSC with IECMH program supervisors, organizational leaders, and policymakers, but questions remain about the defining characteristics and implementation of RSC with these professionals (Amulya, 2004; Hilden & Tikkamaki, 2013).

This paper explores a three-year RSC project that served such leaders in Tennessee, USA. Considerable attention is given to the unique presentation of the:

- Parallel process,

- Ghosts in the Agency, and

- Six characteristics that contribute to defining the concept of Reflective Leadership as it applies to emerging IECMH Leaders.

The Tennessee First Five Training Institute (TFFTI)

In 2019, Tennessee launched the Tennessee First Five Training Institute (TFFTI), a 12-month intensive workforce development project designed to build clinical Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health (IECMH) capacity throughout the state. TFFTI was developed as a response to the growing need for clinical services for children from birth through five to support the state’s growing Safe Baby Court Team. Prior to 2019, Tennessee had a limited history with evidence-based dyadic interventions for children from birth to 72 months (Peak et al., 2021).

TFFTI is unique not only in its intersection of multiple IECMH trainings, but also in its emphatic concentration on organizational development and leadership support. TFFTI selects participants for the annual training cohort based on organizational applications that require the participation of organizational leadership. Annually, six organizations are selected who each identify three to four clinical staff and two organizational leaders for participation. Clinical participants (n=22) and organizational leaders (n=12) engage in year-long parallel training tracks to support the development of IECMH services within their organization (Figure 1).

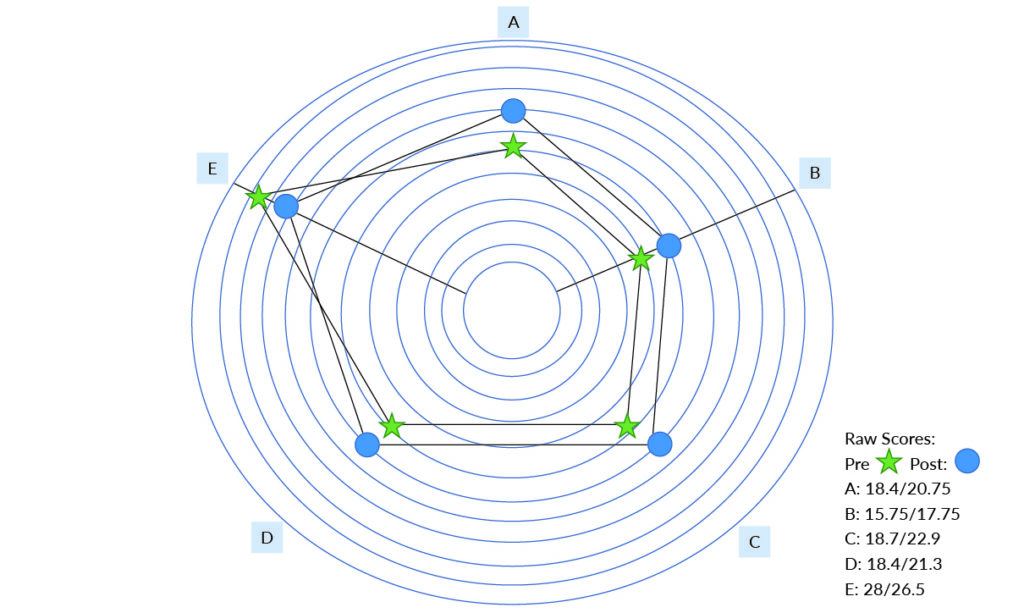

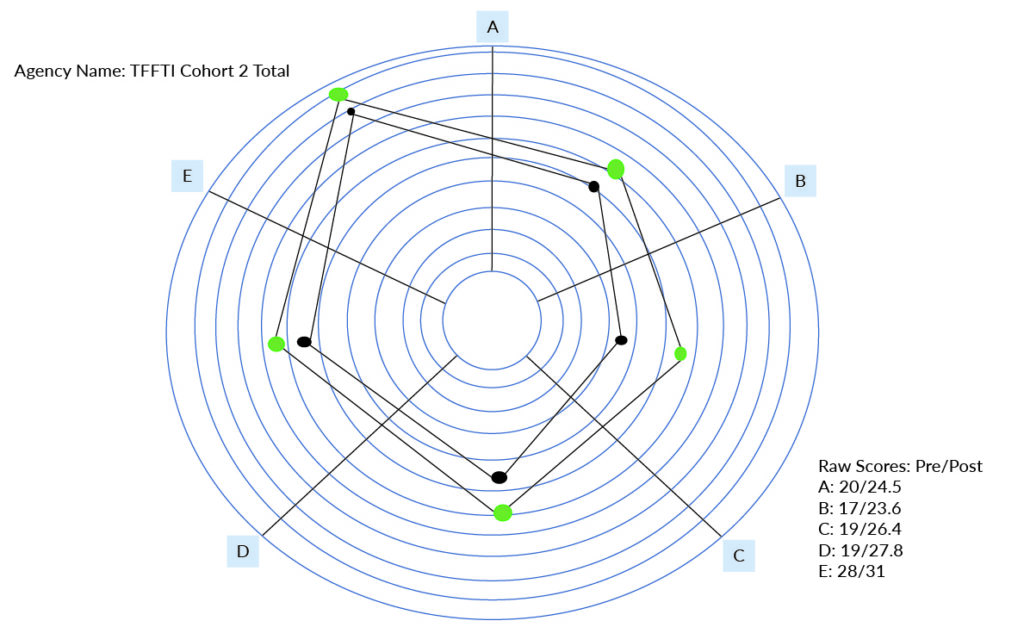

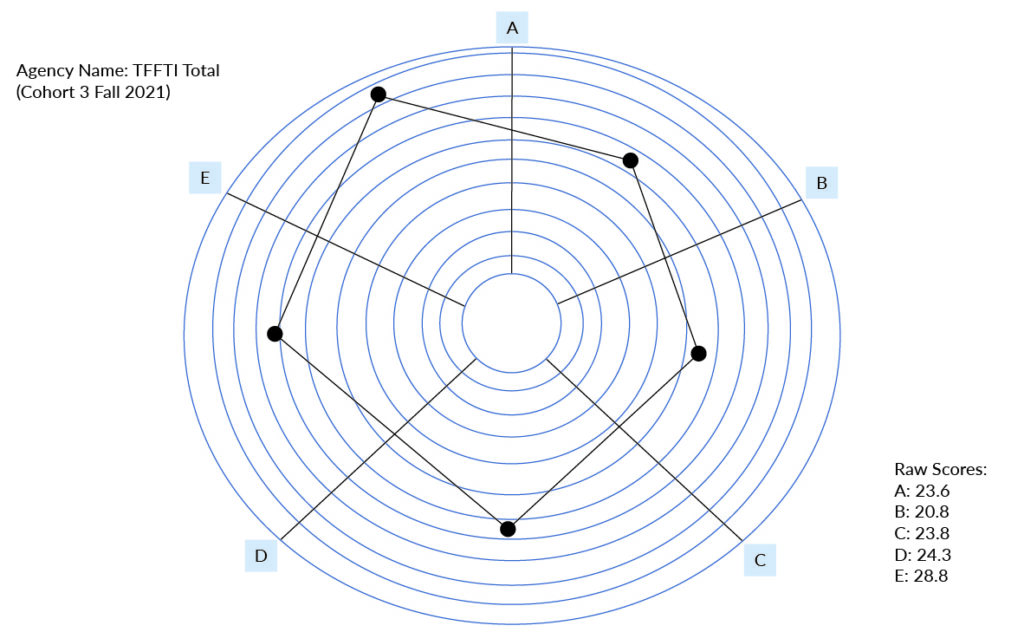

The organizational leaders engage in bimonthly reflective consultation calls, complete an IECMH-focused reading syllabus, and participate in two respective planning summits in the fall and spring of each cohort. Leaders also complete Organizational Readiness for Change Assessments (ORCAs) (twice a year), to assess organizational shifts as a result of participation (Helfrich et al., 2009).

Reflective Supervision/Consultation (RSC)

Selected readings provided leaders with this foundational definition of reflective supervision/consultation (RSC), “a relationship that aims at creating a climate in which both the client and the helper’s needs are being considered, so that the effectiveness of the intervention is being ” (Costa, 2006, p. 124; Heller, 2012, p. 201). RSC offered a routine space to invite slowing down and consideration of multiple perspectives in problem-solving RSC, is a relationship for learning (Pawl, 1995). Within RSC, a relationship between the supervisor and supervisee is intentionally co-created through regular, routine blocks of time in which reflection on a range of clinical and programmatic topics may be thoughtfully considered. Whereas Reflective Practice may be embodied in a variety of activities, RSC is its own separate activity to promote the reflective capacity of the supervisee. Among providers of IECMH services, RSC has been found to increase reflective capacity, decrease staff turnover, and decrease staff experience of secondary trauma (Paradis et al., 2021; Osofsky, 2009).

Consistent with this definition of RSC, TFFTI organizational leaders had an opportunity for reflective practice, defined as the process of carefully considering the qualities and characteristics of one’s ideas and/or actions that go beyond the simple application of professional knowledge (Schon, 1987; Heller, 2012). Within RSC, organizational leaders, thoughtfully considered programmatic changes, set up spaces for thought and questioning without the expectation of answers, and engaged in thoughtful pauses during all logistical meetings.

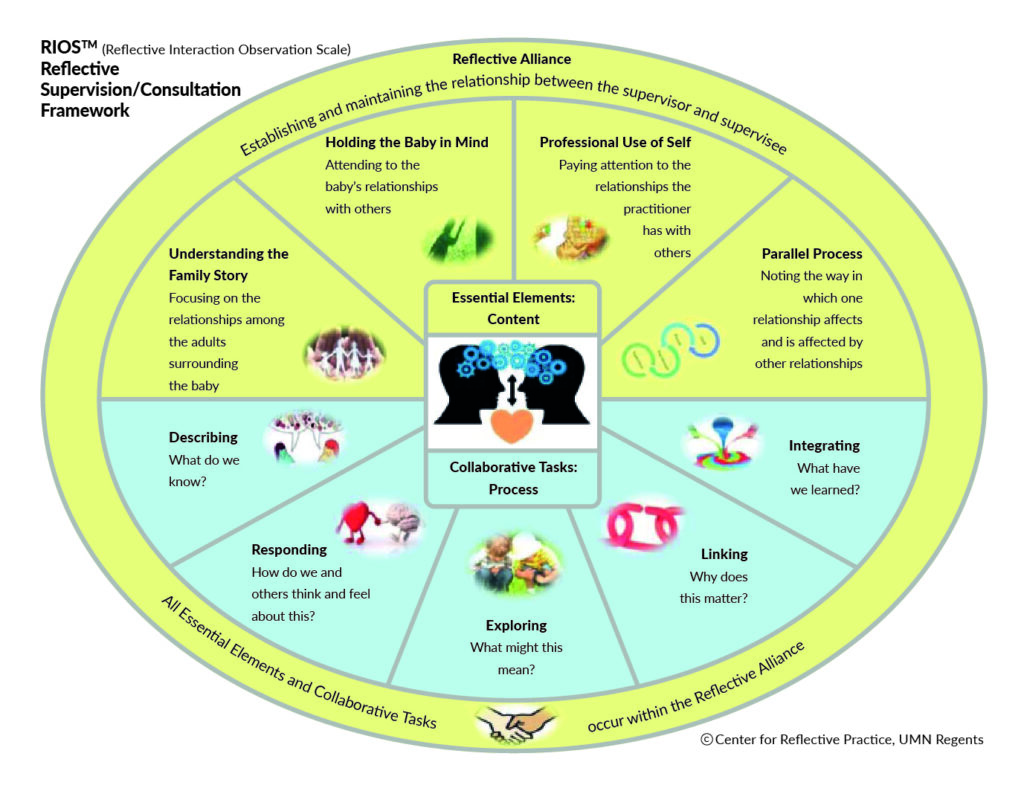

In recent years, considerable efforts have focused on defining the characteristics of RSC that differentiate it from other styles of clinical supervision. These differentiating qualitative aspects are best defined through the Reflective Interactions Observation Scale (RIOS) which identifies five essential elements: understanding the family story, holding the baby in mind, professional use of self, parallel process, and reflective alliance, and five collaborative tasks (describing, responding, exploring, linking, and integrating) (Figure 2) (Watson et al., 2016). The RIOS acts as a guiding framework to acknowledge the complexity of RSC and to highlight the intention of this separate, honored, space.

TFFTI: Engaging Leadership in Reflective/Supervision Consultation

To help promote sustainability in the reflective practice that is foundational for IECMH workforce development, TFFTI’s intensive focus on leadership participation was intended to address the attrition that often occurs in learning collaboratives, to bolster organizations embodiment of IECMH principles beyond front-line staff, and to create sustainability for IECMH services and reflective practice beyond the 12-month learning collaborative. What has emerged far exceeds those original goals, as a rich, cohesive, group of leaders have found new ways of leading, new ways of being through COVID-19, and new opportunities for statewide collaboration from their participation in Reflective Consultation.

Of note, this group elected to refer to this cooperative relationship as “consultation” rather than “supervision” as there were no implications for administrative or clinical oversite between the Consultant and the participants. It was felt that the term consultation better communicated a collegial, voluntary, relationship rather whereas “supervision” was felt to connotate oversight and a power differential.

Twenty organizational leaders, including CEOs and Division Directors, from across Tennessee have participated in the three cohorts. The majority of participants have been women. It is important to note that the leaders of color have been minimal, which parallels the few leaders of color within the limited early childhood behavioral health sector. Each cohort begins with a Fall Summit that invites participants to build upon their understanding of RSC and to develop “road maps” for their identified organizational goals. These goals are unique to each organization and range from adding diagnoses from the DC:0-5™ (Diagnostic Classification of Mental Health and Developmental Disorders of Infancy and Early Childhood) into their Electronic Health/Medical Record (EHR/EMR) to forming workgroups, to increasing IECMH referrals (DC:0-5, 2016).

In the early development of the Organizational Leaders RSC cohort, there were many shared apprehensions about engaging transparently and establishing authentic conversations regarding difficult topics. Many of the participating organizations often competed for grant and programmatic monies and were concerned that sharing staff difficulties or frustrations with organizational policies could negatively impact their work. In lieu of sharing from individual experiences, the cohort began with a syllabus of readings on organizational well-being, organizational trauma, and the role of leadership in workforce sustainability (Vivan et al., 2017).

Selma Fraiberg once stated that working with young children and families was a little like having God on your side (Emde, 1987). In the process of Reflective Consultation, the progress forward often feels a bit the same. The participants came ready to identify similarities between their own experiences of leadership and the educational content. The group began to collectively identify factors that they believed were connected to their own staff’s vicarious trauma and staff turnover which led to considering how these staff concerns resulted in difficulties in providing the quality of services with model fidelity that these leaders desired. As conversations progressed, leaders began to identify their frustration over their inability to control the services being provided to families, to buffer staff from the ever-changing landscape of mental health in COVID-19, and the increased acuity of symptoms with which families presented during the pandemic.

This intentional scaffolding of reflective capacity has been repeated across each cohort. While members are invited to remain a part of the group even if their organization chooses not to participate in the next cohort, group participation does change with each annual cohort. Each fall, the process of applying to participate in TFFTI is repeated, the Summit serves as a kick-off event, and the group regresses slightly in the vulnerability of their conversations, returning to scheduled readings as they resume the process of meeting new individuals and building trust amongst themselves. Notably, this process has not taken quite the length of time in the most recent two cohorts as it did with the initial cohort. Following the initial cohort, some participants remained as new participants joined, contributing established relationships to anchor the addition of new relationships. As is often the case with group Reflective Supervision between a supervisor and direct service providers, the experience of trust amongst existing members and the experience of being in supervision with the consultant provides a solid foundation to form these new relationships as members join the group.

Ghosts in the Agency

The conversations that emerged around the difficulties of staff oversite and support during COVID-19 were vital turning points not only in the group’s ability to engage in RSC, but also in their ability to see themselves as co-creators of the reflective space. One conversation stands out as pivotal in the group’s process and their shared reflective vocabulary. The group consistently referenced the idea of “Ghosts in the Nursery” (Fraiberg et al., 1975) after the assigned reading as it resonated with the organizational trauma that was historically observed in several organizations.

Participants told stories of reactive policy implementation after very specific events or of “legendary” actions by staff that were being retold years after the staff exited the organization. The leaders were able to name their own process of decision-making out of a sense of scarcity and referenced connections to historical layoffs and staff conflict from many years prior as internal motivations for their responses to staff and programmatic needs.

From that discussion, it was named that if there were ghosts and angels in the nursery then there must also surely be ghosts and angels in our organizations. This idea connected to the readings around organizational trauma and also created a powerful connection between the leaders’ daily lived experiences and IECMH theory. It was a moment when the depth of the vocabulary being used matched the depth of the emotion felt by leaders navigating the unseen and often unnamed forces at work in their respective organizations.

As is often the case in RSC, the ability to identify the presence of such ghosts allowed participants to pause and think critically about their present interactions in the workplace. Participants were able to engage in grounding exercises to support themselves and each other in considering if their current efforts at management were relevant to current concerns of the organization or if alternative supports would better achieve desired outcomes and sustainability. Defining and frequently naming the presence of ghosts also allowed for the defining and naming of angels in the agency (Liebermann et al., 2005). With this connecting language, leaders felt included as part of the broader IECMH system, able to ground to the needs of the moment, acknowledge and understand the ongoing impact of the “ghosts” in their organization, and reflect on their ability to show up and be fully attuned with their staff in their current system.

Parallel Process

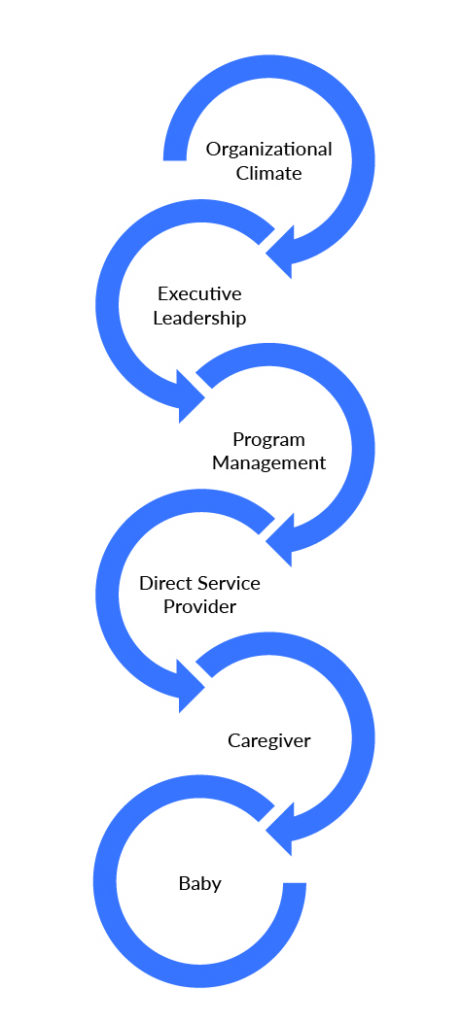

This powerful connection permitted the recognition of an expanded parallel process. In the context of clinical work, the parallel process is often thought of as a connection between the infant/young child to the caregiver, to the service provider, and to the reflective supervisor. Jeree Pawl best sums up the parallel process with “do unto others as you would have others do unto others” (Pawl & St. John, 1998). Much like ripples in water or stacking toys, the parallel process draws an image that each relationship between the infant/young child, the caregiver, and the service provider impacts the other relationships around it. In considering the parallel process through a leadership lens, additional layers of the parallel process became clearer through RSC. It allowed leaders to visualize interactions between the agency administrator, supervisor, and service provider as filtering down to the baby or filtering up from the baby, through the service provider, to the supervisor and agency leaders.

In one such example, a leader processed frustrations with staff experiencing low productivity amid an ever-increasing wait list for services with the agency. The staff reported an increase in no-shows and cancellations and an increase in irritability among families who were returning to office-based services. Through RSC and careful consideration of the parallel process, the leader was able to recognize an increase in staff stress following a return to the office from prior work-from-home policies related to COVID-19 that aligned with increased stress in families who were returning to public places and increased staff in young children who had not been in public spaces for a significant portion of their lives.

In addition to layers reaching to organizational climate, the parallel process was also noted to have greater breadth at a systems level. Leaders began to note correlations in staff reports of feeling heard and decreases in the perceived sense of client acuity. While the connections were not always so clearly delineated, observing and giving words to the experience was impactful on the leaders’ sense of efficacy with their staff. These interactions also paralleled what we know to be effective with RSC between supervisors and direct service providers—that reflective supervision can help buffer against the stressful impacts of the work (Frosch et al., 2019).

The Leader in the Family System

The naming and defining of ghosts in the agency also supported the need for increased definition and contextualization of both the work that was occurring within the Organizational Leaders’ RSC group and the work we were inviting new members to as the group evolved and expanded across cohorts. Additionally, leaders all had some number of clinical staff engaged in their own RSC and frequently had questions about how that RSC process was similar, or different, or how RSC as a general process develops. The group questioned, “How does reflective practice relate to a different style of leadership?” and “Who am I as a leader as a result of participating in this RSC process?” These questions lead to a frame for considering RSC from the perspective of the organizational leader and a clear definition of the contributing attributes of Reflective Leadership.

Typically, RSC is an individual or group space that is regular, relationship-focused, and collaborative in which a supervisor supports supervisee(s) to better understand themselves in the context of the work, to better understand the family they’re serving, and to better understand the connection between the two (Heller, 2012; Shea et al., 2020). As outlined previously, this RSC space intends to utilize the five essential elements and five collaborative tasks outlined within the RIOS, including understanding the family story.

With organizational leaders, the “family story” to be understood has often been the story of the organization itself. These “family stories” have also included the story of how the organization understands its role in providing services, supporting families, and building an IECMH workforce. The “family story” is also called back to the expanded parallel process. Leaders were able to consider this analogy and identify within the “family” of their organization what their role might be and how dynamics between themselves and others might be reminiscent of typical family conflicts.

Additionally, “the baby” referenced in the RIOS presents differently in RSC with leaders. This “baby” is often the most vulnerable perspective in the conversation; a family voice that has gone unheard, an overwhelmed staff that has gotten lost in the attempt to meet programmatic goals or the involvement of other systems and organizations that may have been left out of strategic planning conversations. Consistently within this RSC working with organizational leaders, giving voice to their experiences and helping them to connect those experiences with IECMH direct services facilitated powerful shifts in their reflection and their dedication to systems support for IECMH services.

Understanding Race and Equity in Reflective Spaces of Leadership

The organizational leaders’ call to remember the “baby” and understand the “family story”, has also served as our call to think critically about race and equity within our work. While these conversations are necessary for each of our participants to reflect on individually, the organizational leaders’ cohort is also in a critical space to deeply consider how programs both challenge and uphold systems of racist oppression. Many RSC calls focused on acknowledging the overrepresentation of white service providers serving an overrepresentation of families of color.

The leaders have also consistently noted the lack of colleagues of color within the group itself and the majority of white supervisors throughout the participating organizations. The “family story” of historical trauma was both an ever-present ghost in the organizations and a reminder that with time, effort, and listening to those who live this “story”, that the “story” itself has hope for change. The leaders’ cohort also worked to acknowledge that listening and holding hope were insufficient in addressing the systemic bias and contributions to systemic racism within their respective organizations. The leaders strongly held to Tenets 8, 9, and 10 from the Diversity Informed Tenets for Work with Infants Children and Families, taking time to focus resources on systems change (Tenet 8), making space and open pathways (Tenet 9), and to advance policy that supports all families (Tenet 10) (Frankel et al., 2019).

The RSC space allowed opportunities for the leaders to consider ways that job descriptions, position titles, screening and hiring processes, and benefits packages participated in that systemic oppression and worked to create concrete plans to change those areas of concern. Individual organizations incorporated these action items into their “roadmaps” to identify the steps their organizations could take in moving toward greater inclusivity.

Defining Reflective Leadership

Shared language and identifying connections between existing concepts and the experience of leadership were key to establishing the leaders’ RSC group, developing group cohesion, and maintaining participation. The organizational leaders’ cohort found ways to shift definitions or to consider the application of concepts through a systems lens, such as the discussion of ghosts in the agency and the expanded parallel process. However, this group struggled to embody a definition of Reflective Leadership and Reflective Organizations.

While previous articles discussing Reflective Leadership in the IECMH world do exist, participants felt that the leadership demands of COVID-19 and remote work left the existing literature feeling as though it was missing something (Parlakian & Siebel, 2001; Amulya, 2004; Hilden & Tikkamäki, 2013; Göker & Bozkus, 2017; Schmelzer & Eidson, 2020). As the cohort consulted articles and blogs from Industrial/Organizational Psychology and Harvard Business Review, there were many concepts and conversations that were connected to Reflective Practice or that sometimes were even referred to as Reflective Practice, and yet missed many of the key facets that Reflective Practice embodies within IECMH work. For example, a regular space to process challenges with a consistent reflective supervisor. Göker and Bozkus (2017) in their discussion of Reflective Leadership, acknowledge the need for shifts in leadership frameworks in response to changes in our broader world.

This review of available information led to the development of a two-part definition of Reflective Leadership for the Spring Summit. This definition was developed to ground the group to the shared themes and vision that they had communicated throughout the biweekly reflective consultation calls. The definition was an aspiration to encompass not only what leaders were doing, but also what they sought as part of their contributions to their personal and organizational development.

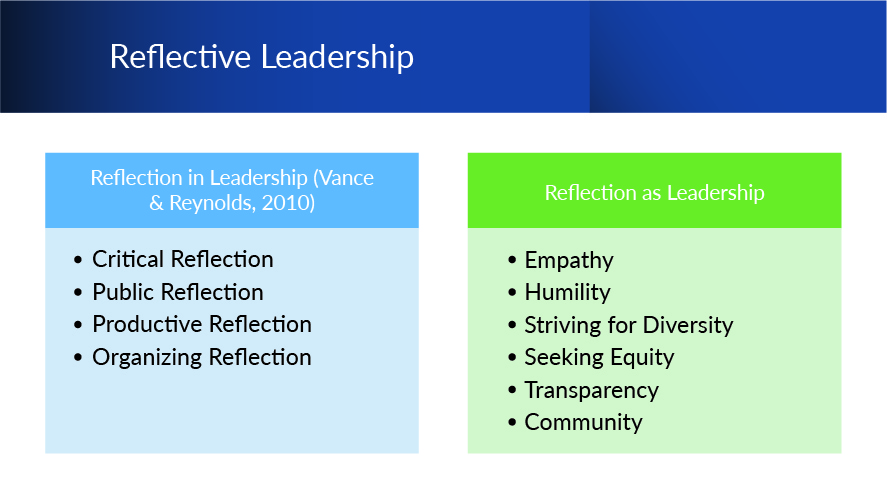

Reflective Leadership in its two-part definition includes a) Reflection in Leadership and b) Reflection as Leadership (Figure 4). Reflection in Leadership utilized the four types of reflection as defined by Vance and Reynolds (2009) as anchoring points to consider ways in which leaders engage in reflection with their colleagues and staff in an effort to move forward with programmatic vision, expectations, and goals.

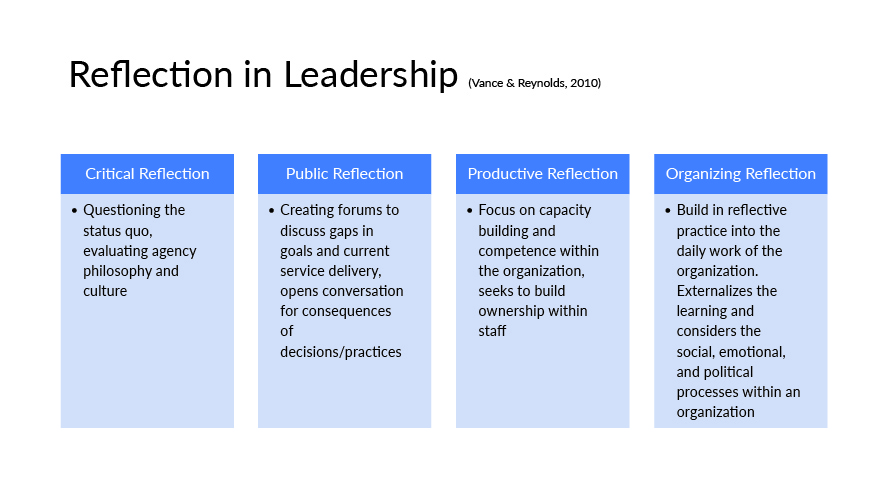

Reflection in Leadership (Vance & Reynolds, 2009)

Vance and Reynolds identify the concepts of critical reflection, productive reflection, public reflection, and organizing reflection as ways for leaders to consider how they invite conversation within their organization, how they responded when concern or praise is raised, and how staff within the organization might feel as a result of their involvement in these processes (Figure 5). While these four types of reflection helped build the leaders’ sense of efficacy with communication, they did not reach the depth of the relational aspect that RSC embodies. These four definitions also left the cohort wondering how leadership is different when RSC is implemented and held as a personal priority. The need to address these two experiences resulted in the development of Reflection as Leadership as an additional component for this definition.

Reflection as leadership

Reflection as Leadership identifies six characteristics; empathy, humility, striving for diversity, seeking equity, transparency, and community, that act as guiding tenets. Much like the Diversity Tenets, these six characteristics are not boxes to be marked as completed, but qualities and goals to be worked towards consistently throughout one’s leadership career (Frankel, Njoroge, & Norona, 2019). Like an image of a small child holding many balloons, these six characteristics act as strands to be held in mind, acknowledged when they’ve been let go of, and regained with the help of others as quickly as possible.

Additionally, the characteristics also called to mind the RSC practice of spotlighting which acknowledges the need for a provider’s priority and focus to shift and change in response to the situation at hand (Heller, 2012).

The characteristic of Empathy is best summarized through Brene Brown’s quote “Empathy has no script. There is no right way or wrong way to do it. Its simply listening, holding space, withholding judgement, emotionally connecting, and communicating that incredibly healing message of ‘You’re not alone.’” (2015, p. 91). The characteristic of empathy in leadership, as in life, requires that we show up and listen to what others are telling us and to sit with their emotions. It does not require that we change our minds in our leadership decisions or that we shift direction in programmatic goals, but it does call us to be present with the emotions of those implementing the change.

Humility encourages the utilization of self-awareness, of limitations of ourselves both as humans and leaders, and for leaders to build their reflective capacity to know those limitations. Humility in context further encourages the Leader to acknowledge when their strengths or weaknesses might contribute to organizational growth or struggle, to acknowledge when they don’t have the answers to the problem at hand, and to be willing to ask for help from staff or others in moments when the attributes of others would be better suited to move the work forward.

Striving for Diversity was intentionally worded in this combination as Leaders within this group recognized that Diversity itself was not the endeavor, but that rather the work was of addressing racial inequities in leadership positions, making space and opening pathways to allow for greater representation within systems, and to recognize diversity in various forms of race, ethnicity, country of origin, and ability status. The wording of this characteristic also allows it to stand as a call to action, a reminder that the work will never be complete, but that the success of brown and black colleagues, families and children, is central to the success of all staff, all families, and all children.

Likewise, Seeking Equity challenges leaders to consider how access impacts service delivery, staff retention, staff engagement in RSC, retention of families in services, family success by program, etc. Highlighting equity as access also encourages leaders to consistently hold in mind the “baby.” To acknowledge that all situations have a “baby”, a perspective or person in a position of disparity calls for leaders to slow down their decision-making process and be intentional about the intended and unintended consequences of those decisions.

The characteristics of Transparency and Community round out the six characteristics included in Reflection as Leadership. Transparency requires Leaders to acknowledge their own emotions within the experience of leadership, to share those emotions as appropriate with staff, and to openly acknowledge moments of uncertainty and where there is a lack of answers. Transparency is not oversharing personal experiences or burdening staff with details of potential struggles that have not yet fully come to light. It is however the process of creating an inclusive experience where the characteristics of empathy and humility are verbalized and shared throughout the organizational hierarchy.

Lastly, the characteristic of Community holds that leading with a reflective stance ultimately means not leading alone. The characteristic of community, this sense of togetherness, and the acknowledgement of shared humanity is a key aspect of RSC as a practice. The Leaders who participated in TFFTI repeatedly commented on how different their work felt because they felt less alone. The sense of Community also promoted our group’s awareness that the situations they were navigating were often the result of Ghosts in the Agency and not their own shortcomings as individuals. Community allowed them to gain perspective on situations, hear the “family story,” hold the “baby” in mind, and sit in the hard work of beginning race and equity journeys for themselves and on behalf of their programs. Community allowed many of our participants a gathering place of support and shared vision for the first time in their leadership tenure.

Discussion

As with RSC with clinical providers, the RSC space with organizational leaders continues to emphasize the personal experience of the leader themselves, their ability to hold the perspective of the team they are supervising, and how the interconnection between those perspectives impacts the work with infants, young children, and families (Schmelzer & Eidson, 2020). While not discussed in this article, considerable data measures, such as the Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory (FMI) (Walach et al., 2006) and the Curiosity and Exploration Inventory-II (CEI-II) (Kashdan et al., 2010), have been taken with the Leaders who have participated in TFFTI for these three cohorts.

TFFTI adapted the Organizational Readiness for Change Assessment (ORCA) (Helfrich et al., 2009) to focus on the implementation of IEMCH concepts and evidence based-practices in an effort to measure the impact that support for leaders would have on organizational outcomes. While not discussed in this article, those outcomes have been notable and support that the work of RSC with leaders, defining the work of leadership in IECMH settings, and creating the framework of Reflective Leadership has had an impact on the leaders, the staff, and their broader organizations.

Over the duration of the three-year project, participants have increased their ability to engage in vulnerable conversations about things they initially expressed reluctance to discuss, such as: discussing staff concerns, addressing organizational decisions that they disagreed with, and thinking collaboratively about how organizations could work together to improve the provision of services for infants, young children and their families and care for the IECMH workforce across the state.

Further efforts are needed to replicate these concepts with other cohorts of leaders in various geographical settings and from other sectors to identify consistencies and deviations from the experiences noted here. Additional data collection and evaluation should also be considered to identify the individual change in the reflective capacity of leaders over the duration of their participation in Reflective Supervision. Investigating the differences in the content and delivery of RSC with leaders would also be of considerable value to the field much as the RIOS helped to identify the core components of providing RSC with direct care staff.

Conclusion

RSC is a cornerstone for IECMH direct practice across the continuum of IECMH services. However, its utilization with programmatic, organizational, and policy leaders has been limited to date. This article explores the application of the clinical concepts of ghosts in the nursery (Fraiberg et al., 1975) and parallel processes to organizational leaders and in turn, proposes a working understanding and definition of Reflective Leadership. Preliminary consideration for data collection methods is also discussed.

While the experience has been both relationally powerful and quantitatively impactful for the current participants, more work is necessary to define reflective organizations and to consider how the reflective capacity and cultural embodiment of reflective practice might be measured within organizations. Additionally, greater detail is warranted to explore the confluence of Reflection in Leadership and Reflection as Leadership as the culminating characteristics of Reflective Leadership within IECMH service systems.

Acknowledgements:

TFFTI would like to acknowledge the contributions and support of Association of Infant Mental Health in Tennessee (AIMHiTN), BlueCare of Tennessee, Tennessee Department of Children’s Services-Building Strong Brains Initiative, Tennessee Association of Mental Health Organizations, and Lynsey Rose. Without their individual contributions and support, this project and its data would not be possible. TFFTI also acknowledges the contributions of one of the Organizational Leaders, Andrea Chase, who lost her battle with COVID in 2020. Her thoughts and perspectives were invaluable to Tennessee’s IECMH workforce development.

References

Amulya, J. (2004). What is reflective practice? Center for reflective community practice at MIT. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.737.3650&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Brown, B. (2015). Daring Greatly: Penguin; New York, New York.

Dutton, J. E., Frost, P. J., Worline, M. C., Lilius, J. M., & Kanov, J. M. (2002). Leading in times of trauma. Harvard Business Review, 80(1), 54-61.

Emde, R. N. Foreword. Selected Writings of Selma Fraiberg edited by Louis Fraiberg, Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press, (1987), p. xix.

Frankel, K., Njoroge, W., & Norona, C. R. (2019). The Diversity Informed Tenets for Work with Infants, Children, and Families: A tool for promoting diversity-informed clinical practice Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 58(10) ppS383

Fenichel, E. (1992). Learning through Supervision and Mentorship to Support the Development of Infants, Toddlers, and Their Families in E. Fenichel (Eds.), Learning through Supervision and Mentorship: A Source Book (pp 9-17) ZERO TO THREE

Fraiberg, S., Adelson, E., & Shapiro, V. (1975). Ghosts in the Nursery. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry 14, 387-42.

Fonagy, P., Gergely, G., Jurist, E., & Target, M. (2002). Affect Regulation, Mentalization and the Development of the Self. New York: Other Press

Frosch, C. A., Mitchell, Y. T., Hardgraves, L., & Funk, S. (2019). Stress and coping among early childhood intervention professionals receiving reflective supervision: A qualitative analysis. Infant Mental Health Journal, 40(4), 443-458. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21792

Göker, S.D., & Bozkuş, K. (2017). Reflective Leadership: Learning to Manage and Lead Human Organizations. In Contemporary Leadership Challenges (Eds) Alvinius, A. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/5a0b/08c86eafe368d0cc79182ebf57bb47479519.pdf?_ga=2.105589059.1509634871.1659510008-1154751480.1659510008

Harrison, M. (2016). Release, reframe, refocus, and respond: A practitioner transformation process in a reflective consultation program. Infant Mental Health Journal, 37(6), 670-683. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21606

Helfrich, C., Yu-Fang L., Sharp, N, & Sales, A. (2009). Organizational Readiness for Change Assessment (ORCA): Development of an instrument based on the promoting action on research in health services (PARIHS) framework Implementation Science 4(38).

Heller, S. S. (2012). Reflective supervision. Understanding early childhood mental health: A practical guide for professionals, 199-216.

Hilden, S., & Tikkamäki, K. (2013). Reflective practice as a fuel for organizational learning. Administrative Sciences, 3(3), 76-95. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci3030076

Jansson von Vultée, P. H. (2015). Healthy work environment – a challenge? International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance, 28(7), 660–666. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJHCQA-11-2014-0108

Kashdan, T., Gallagher, M., Silvia, P., Winterstein, B., Breen, W., Terhar, D., & Steger, M. (2010). The Curiosity and Exploration Inventory-II: Development, factor structure, and psychometrics PubMed Central 43(6), 987-998.

Kononowech, J., Hagedorn H., Hall, C., Helfrich C., Lambert-Kerzner, A., Miller, S. C., Sales, A., & Damschroder, L. (2021). Mapping the Organizational Readiness for Change Assessment to the consolidated framework for implementation research Implementation Science Communications 2(19) https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-021-00121-0

Lieberman, A. F., Padrón, E., Van Horn, P., & Harris, W. W. (2005). Angels in the nursery: The intergenerational transmission of benevolent parental influences. Infant Mental Health Journal: Official Publication of The World Association for Infant Mental Health, 26(6), 504-520.

Liebermann, A, Gosh Ippen C., & Van Horn, P. (2015). Don’t Hit My Mommy! ZERO TO THREE

Lindberg, P., & Vingård, E. (2012). Indicators of healthy work environments – a systematic review. Work, 41, 3032–3038. https://doi.org/10.3233/wor-2012-0560-3032

Norona, C. R. & Acker, M. (2016). Implementation and Sustainability of Child-Parent Psychotherapy: The Role of Reflective Consultation in the Learning Collaborative Model. Infant Mental Health Journal 37(6), 701-716.

Osofsky, J. D. (2009). Perspectives on helping traumatized infants, young children, and their families. Infant Mental Health Journal, 30(6), 673–677.

Paradis, N., Johnson, K., & Richardson, Z. (2021). The value of reflective supervision/consultation in early childhood education ZERO TO THREE Journal 41(3) 68-75.

Parlakian, R., & Seibel, N. (2001). Being in charge: Reflective leadership in infant-family programs. Washington, DC: ZERO TO THREE.

Pawl, J., & St. John, M. (1998). How you are is as important as what you do in making a positive difference for infants, toddlers and their families. Washington, D.C.: Zero to Three.

Pawl, J. (1995). The therapeutic relationship as human connectedness: Being held in another’s mind ZERO TO THREE Journal, Feb/Mar 1995.

Peak, A., Kronenberg, M., Morelen, D., Norona, C. R., Frankel, K., & Webster, A. (2021). Being with…By Zoom?: Tennessee’s story of continuing IECMH workforce support and development in the time of COVID-19. ZERO TO THREE Journal 41(4).

Schmelzer, M., & Edison, F. (2020). The intersection of leadership and vulnerability: Making the case for reflective supervision/consultation for policy and systems leaders The Infant Crier November 10, 2020.

Schön, D. A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner: Toward a new design for teaching and learning in the professions. Jossey-Bass.

Shea, S. E., Goldberg, S., & Weatherston, D. J. (2016). A community mental health professional development model for the expansion of reflective practice and supervision: Evaluation of a pilot training series for infant mental health professionals. Infant Mental Health Journal, 37(6), 653-669. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21611

Shea, S. E., Jester, J. M., Huth‐Bocks, A. C., Weatherston, D. J., Muzik, M., & Rosenblum, K. L. (2020). Infant mental health home visiting therapists’ reflective supervision self‐efficacy in community practice settings. Infant Mental Health Journal, 41(2), 191-205. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21834

Tomlin, A. M., Hines, E., & Sturm, L. (2016). Reflection in home visiting: The what, why, and a beginning step toward how. Infant Mental Health Journal, 37(6), 617-627. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21610.

Tomlin, A. M., Weatherston, D. J., & Pavkov, T. (2013). Critical components of reflective supervision: Responses from expert supervisors in the field. Infant Mental Health Journal, 35(1), 70-80. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21420

Vance, R., & Reynolds, M. (2009). Reflection, reflective practice and organizing reflection. In The sage handbook of management and learning, education and development (pp. 89-103). https://doi.org/10.4135/9780857021038.n5

Vivian, P., Cox, K., Hormann, S., & Murphy-Kangas, S. (2017). Healing traumatized organizations: Reflections from practitioners OD Practitioner 49(4), 45-51.

Vivan, P., & Horman, S. (2015). Persistent traumatization in nonprofit organizations OD Practitioner 47(1), 25-30.

Walach, H., Burchheld, N., Buttenmuller, V., Kleinknecht, N., Schmidt, S., (2006). Measuring mindfulness: The Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory Personality and Individual Differences, 40(2006), 1543-1555.

Watson, C. L., Harrison, M. E., Hennes, J. E., & Harris, M. M. (2016). Revealing “The Space Between”: Creating an observation scale to understand Infant Mental Health reflective supervision. Zero to Three, 37(2), 14-21.

ZERO TO THREE. (2016, 2021) DC:0-5: Diagnostic classification of mental health and developmental disorders of infancy and early childhood. Washington DC: ZERO TO THREE.

Authors

Peak, Alison D.,

Allied Behavioral Health Solutions, Nashville TN

Morelen, Diana,

East Tennessee State University, Johnson City TN

Johnson, Katherine,

Allied Behavioral Health Solutions, Nashville TN

Timmins, Emma,

Allied Behavioral Health Solutions, Jefferson City TN

Kronenberg, Mindy,

Private Practice, Memphis Tennessee

Webster, Angela,

Association of Infant Mental Health in Tennessee