Introduction

This paper describes a one-day Infant Mental Health (IMH) workshop which was held for all staff at Childhood Matters, irrespective of their professional role. Childhood Matters is an NGO in Cork, Ireland. The training day was also evaluated. Forty-seven staff attended the workshop and data from thirty evaluation forms is reported. Of these thirty, nine were by staff who were from a non-clinical background (administration, horticulture, security etc). This paper focuses on the evaluation data provided by the non-clinical staff. Although a small sample, it was felt that these were most representative of the general public perspective regarding infant mental health and wellbeing. As such, there was potential to learn about gaps in service awareness and overall public awareness within the Irish context. In analysing this evaluation data, this paper reports on three over-arching themes concerning the ongoing task of IMH awareness and promotion regarding early childhood social and emotional development so that this knowledge is on par with what is already known about physical development to the Irish public.

The organisational and country context

Childhood Matters is a non-profit organisation located on the outskirts of Cork city, Ireland. It is made up of a number of different services inclusive of a parent and infant residential unit which provides parenting capacity assessments, a community family support programme, a creche, a preschool, a teen parents programme, a back-to-education programme and an employment support scheme. The organisation provides child and family services which are aimed at supporting and promoting positive childhood outcomes, developing and understanding parenting capacity and building overall family resilience, contributing to healthier and more sustainable communities. Childhood Matters aims to provide services that support and promote the optimal health and well-being of families at the earliest possible stage. The Childhood Matters staff body is made up of a wide range of disciplines ranging from an executive team to early childcare providers and horticulturalists.

Every year, Childhood Matters connects with over 1000 children through their community and residential services. The service recognises the importance of highlighting the area of Infant Mental Health to staff, families, and the wider community. The service has a Senior Clinical Psychologist and Infant Mental Health specialist affiliated with the Irish Association of Infant Mental Health who provides guidance and training to all staff as well as working directly with parents and families.

The Irish Association for Infant Mental Health (IAIMH) was established in 2009 and is affiliated with the World Association for Infant Mental Health (WAIMH). IAIMH is a non-profit national organisation and a registered charity which was established to promote IMH and provide services to advance the well-being of infants and their caregivers using an interdisciplinary approach (Maguire & Matacz, 2012).

The project

While there is a growing impetus on Infant mental health practices, there are still considerable gaps in service awareness and overall public awareness within the Irish context. To bridge this gap, tailored infant mental health training was required to develop a common language and fluency regarding early childhood social and emotional development which is on par with what is already known about physical development to the Irish public.

Developing the IMH training for all staff within the organisation

Following best practice guidelines and in keeping with the relational approach in Childhood Matters, a one-day training on Infant Mental Health principles was conducted for all staff irrespective of profession or expertise. A public health training approach was therefore adopted to ensure the relevancy of the material to employees from all backgrounds.

The Irish Association for Infant Mental Health Competency Guidelines* (2018) provide professionals with a framework in which to deliver infant mental health knowledge within work settings and across all sectors and disciplines working on promotion, prevention, treatment intervention and policy. In the development of this training programme, these guidelines were consulted and a common language was developed to communicate infant mental health through a blended learning approach.

Participants

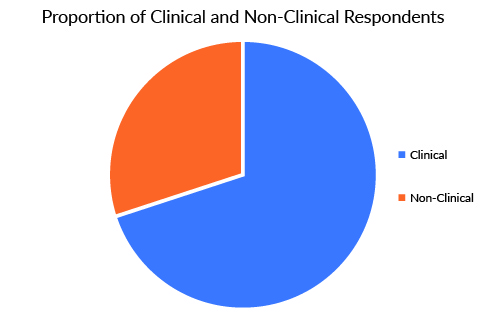

Forty-seven employees from Childhood Matters took part in either one of two training days, which were held within the service. Participants were from a range of disciplines and different areas of the service, representing those who worked both directly and non-directly with families. Twenty-two per cent of those in attendance represented staff who did not work directly with families such as those in the Administration and Executive team, Domestic and Household staff, Security, Maintenance and Horticulture staff. The remaining seventy-eight per cent consisted of clinicians, early educators, teachers and family development practitioners.

To facilitate recruitment, an information poster was circulated to staff outlining the importance of Infant Mental Health and its relevance to the service as a whole. Managers from each department agreed to make the necessary arrangements needed so that their staff could attend either one of the two training days organised. Both training days were mixed so that there was a representation of staff who worked directly with families and those who worked non-directly.

The Training

The training was scheduled from 9 am to 4 pm. Lunch and refreshments were provided for all those in attendance on the day. The workshop was designed and presented by the Senior Clinical Psychologist and Infant Mental Health Specialist. The content of the workshop was guided by the foundation skills and competencies listed in the Irish Association for Infant Mental Health Competency Guidelines® (2018). As such, the training sessions focused on the four core areas: What is IMH, and Why it is Important, Brain Development, Foundation Pillars of Attachment, and Emotional Regulation. A blended learning approach was used meaning the information was disseminated using a mix of video and oral-based presentations, a group-based task, and opportunities for discussion.

The Brain Architecture Game was utilized as a group activity during this training. This game was developed by both the National Scientific Council on the Developing Child and the FrameWorks Institute in America. The game is interactive and team-based and illustrates the powerful role that relationships have on early brain development focusing in particular on the type of experiences that promote and derail brain development and the overall consequences for society (The Brain Architecture Game, n.d.).

Evaluation of attendees’ experiences of the training

Evaluation aim

The aim was to evaluate the training day and ascertain whether the workshop and information provided were easily accessible to those in attendance with a particular focus on those from a non-clinical background.

Evaluation of the training was conducted in the form of a questionnaire administered to all attendees post-training. The questionnaire contained 14 questions which were a mix of yes/no responses and Likert scales with an opportunity to provide additional feedback in a textbox. The questions analysed whether the attendees felt the training was of use for them in their daily lives; whether the information presented was easily accessible and understood; the main messages taken from the training and any changes they might make. Evaluations were circulated to attendees on completion of training. All questionnaires were completed anonymously and two evaluation boxes were placed in different parts of the campus where staff could return their completed form to. Attendees were given a timeframe of three weeks to return completed forms.

Results

Of the forty-seven evaluation forms which were administered, thirty forms were returned for analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to analyse the results. See Figure1 for a breakdown of clinical and non-clinical respondents.

When asked if the attendees had previously heard of Infant Mental Health before completing the training, twenty-two reported that they were previously aware of this term and eight responded that they were not. Of those who reported they were aware of the term, respondents indicated that they had acquired this knowledge through their area of study in their undergraduate and post-graduate degrees.

When asked to comment on what they found particularly interesting or helpful about the training day, the answers from the non-clinical population shed interesting light on the dissemination of this information to the general public. One non-clinical respondent wrote “I found it fascinating to learn how a baby’s experiences in its first hours, days and weeks are critical to its well-being in later life. I found it very interesting to learn how communicating with your baby through gazing and mimicking their sounds has such a huge impact on their social and emotional development and plays a key role in emotional regulation in later years. I found it both helpful and reassuring that a parent/guardian only has to be good enough”.

Another non-clinical respondent commented, “I thought we thought about mental health when we were older. That was a real surprise. To be aware of the mental health of babies and toddlers is wonderful information to have. It is so helpful.

When asked if they felt that this training gave them a good understanding of IMH, all thirty respondents reported that it had. Several respondents commented that the teamwork exercises and video content aided in their understanding of IMH.

In response to the question “Please rate how confident you would feel giving a basic explanation of IMH to a friend/colleague/family member”, three responded that they would feel extremely confident, twelve responded that they would feel very confident and eight responded that they would feel confident. Five of the respondents reported that they would feel somewhat confident and two reported that they would not feel confident explaining IMH.

One of the participants who reported that they would not feel confident explaining IMH commented “It gave me a better understanding, but I would not feel confident to relay this to others. Maybe if it was a 2-3 day training, I would be more confident and feel I understood more”.

Sixteen participants responded that they felt it was extremely important for the general public to have a basic understanding of IMH, ten reported that they felt it was very important and four stated that they felt it was important. When asked to comment on their response, one participant wrote, “The first three years are extremely important in children’s lives. Their brain develops very first and the relationship you form with your child is fundamental to their future”.

Another respondent commented, “The early days, weeks and months of an infant’s life are crucial in terms of brain development, affect regulation and emotional wellbeing. If there were a greater understanding of this, it could have the potential to change entire societies”. Comments from the non-clinical respondents included “Extremely important – I think that the general public should be made aware that infancy is a critical period for social and emotional development and that down the line, emotional and behavioural difficulties could be avoided. Society, in general, would reap the rewards”.

Another non-clinical respondent commented, “Extremely important – because most people don’t think of the mental health of babies and toddlers as an issue, yet, as we learned how so very important is it in the first months and early years for the mental health of those little ones”.

Respondents were asked to list the main points that they took from the training day and some of the comments included information such as,

- “Repair is possible”,

- “Relationships are at the heart of social and emotional development. All development happens within a relational context” and

- “Infant mental health needs to be recognised more widely and focused on more in an effort to prevent later difficulties”.

Several respondents also referred to the importance of understanding and acknowledging Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACES) (Felitti et al., 1998).

Answers from the non-clinical respondents to this question included comments such as:

- The importance of communicating with a baby through gazing/mimicking/sounds. A parent/guardian needs to only be good enough.

- The importance of a good foundation for healthy brain development and the powerful impact this has on social and emotional development, and

- The mental health of babies and toddlers is vitally important; these early years are vital for them to develop mentally and that their supports within the family are sound.

Emerging themes

Three primary themes from the evaluation data are presented here:

- Surprise to hear about the emerging capacities of the infant from birth,

- The importance of building strong foundations concerning an infant’s brain development, and

- The mental health of babies and toddlers.

- Surprise to hear about the emerging capacities of the infant from birth

Of note was the responses of non-clinical respondents who commented on how surprised they were to hear of the emerging capacities of the infant from birth, specifically, their need and desire to communicate with the primary caregivers through mutual gaze and mimicking of facial expressions and sounds. One respondent noted their surprise at how integral communicating with an infant was to their later life development. This observation was further advanced by another respondent who considered it interesting to learn about just how young babies can take in what is going on around them.

Based on these responses, one could postulate that the general public is still relatively unaware of the emerging capacities of an infant from the time of birth and how infants depend on the reciprocal nature of the parent-infant relationship to develop a sense of themselves and a sense of their identity.

- The importance of building strong foundations with regard to an infant’s brain development.

When asked about what main points they took from the training, several non-clinical respondents reported that they noted the importance of building strong foundations for their baby through relational or ‘serve and return’ activities and communication. The Centre for the Developing Child (2012) states that these serve and return activities are integral for neural wiring and brain development in infancy.

Consequently, from a public health perspective, this information needs to be made accessible to the wider public. Translating and disseminating infant mental health knowledge and principles at a public health level could provide parents and caregivers with greater awareness and understanding of the key skills and capacities required to give their infant’s the best possible start in life.

- The mental health of babies and toddlers.

The third theme to emerge from the data was the mental health of babies and toddlers. While many of the clinical respondents were familiar with the term, several non-clinical respondents remarked how they previously thought the term Mental Health could be applied to adults and never associated it in relation to the social and emotional development of infants. This evaluation provides us with valuable insight into the wider public’s awareness of these issues. While most respondents stated that they had previously heard of the impact of ACE’s on later life, most reported they had been unaware of the importance of an infant’s experiences in utero, after birth and the first 18 months. Research has consistently demonstrated that this time is most pivotal for the developing brain and human development in terms of life-long health and well-being; neural development is most vulnerable to adverse childhood and environmental experiences (Bergner, 2008; Barlow, 2013).

Conclusion

Infant Mental Health matters and an understanding of what constitutes as good infant mental health and good enough parenting is imperative to the growth and development of secure, healthy present and future generations. On examination of data obtained from the non-clinical respondents, many noted that they were unaware of the term Infant Mental Health and were surprised to hear about both the emerging capacities of the infant from birth and the importance of an infant’s experiences in utero, after birth and during the first 18 months. These respondents also remarked on learning about the significance of the parent-infant relationship namely the significance of serve and return communication for promoting healthy brain development and helping infants to build a sense of themselves and a sense of their identity.

The non-clinical population represented those who did not work or study in an area which would directly expose them to the importance of Infant Mental Health and early years development, this population is likely to be representative of the general public. This, therefore, highlights the need to disseminate IMH knowledge and information to make it publicly accessible to all. In addition, it highlights the ongoing challenge within IMH promotion, to continue to build knowledge and understanding about early childhood social and emotional development so that this knowledge is on par with what is already known about physical development to the Irish public.

To address the gaps that currently exist in the awareness of Infant Mental Health among the Irish general public, improving access to IMH knowledge and resources is crucial. Moving outside this staff population and providing the general public with opportunities to attend Infant Mental Health workshops and incorporating the dissemination of IMH information and learning into public policy would be a start in bridging this gap.

References

Barlow, J. (2013). Parenting during the first two years and public mental health. In Lee Knifton & Neil Quinn (eds.) Public Mental Health Global Perspectives, McGraw Hill Education; Open University Press.

Bergner, S., Monk, C., & Wagner, E. A. (2008). Dyadic intervention during pregnancy. Treating pregnant women and reaching the future baby, Infant Mental Health Journal, 29, 399-419.

Clinton, J., Feller, A. F., & Williams, R. C. (2016). The importance of infant mental health. Paediatrics & child health, 21(5), 239-241.

Davis, E., Sawyer, M. G., Lo, S. K., Priest, N., & Wake, M. (2010). Socioeconomic risk factors for mental health problems in 4–5-year-old children: Australian population study. Academic Pediatrics, 10(1), 41-47.

Early Childhood Development. The World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/earlychildhooddevelopment#.

Eccles, M. P., & Mittman, B. S. (2006). Welcome to Implementation Science . Implementation Sci 1, 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-1-1.

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258.

Irish Association for Infant Mental Health Competency Guidelines® (2018). I-AIMH Endorsement for culturally Sensitive Relationship Focussed Practice Promoting Infant Mental Health.

Lyons‐Ruth, K., Todd Manly, J., Von Klitzing, K., Tamminen, T., Emde, R., Fitzgerald, H., Campbell, P. Keren, M., Berg., A., Foley, M., & Watanabe, H. (2017). The worldwide burden of infant mental and emotional disorder: report of the task force of the world association for infant mental health. Infant Mental Health Journal, 38(6), 695-705.

Maguire, C., & Matacz, R. (2012). Bridging the Gap in Service Development in North Cork and Primary and Continuing Care: The Development and Integration of an Infant Mental Health Model into Existing Service Delivery, Child Links Infant Mental Health: The Journal of Barnardo’s Training and Resources Service, 2, 30-34.

Moore, T. G., Arefadib, N., Deery, A., & West, S. (2017). The First Thousand Days: An Evidence Paper. Parkville, Victoria; Centre for Community Child Health, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute.

Rabin, B. A., & Brownson, R. C. (2012). Developing the terminology for dissemination and implementation research. In R. C. Brownson, G. A. Colditz, & E. K. Proctor (Eds.), Dissemination and implementation research in health (pp. 23–51). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Serve and Return. Centre on the Developing Child, Harvard University. https://developingchild.harvard.edu/science/key-concepts/serve-and-return/.

Shonkoff, J. P., & Phillips, D. A. (2000). From Neurons to Neighbourhoods: The Science of early childhood development. Committee on Integrating the Science of Early Childhood Development, National Research Council & Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

The Brain Architecture Game. (n.d.) https://dev.thebrainarchitecturegame.com/ .

Authors

de Búrca, Isobel,

Ireland

Maguire, Catherine,

Ireland

Ross, Alasdair,

Ireland

We would like to sincerely thank both the staff and management at Childhood Matters for taking part in this evaluation.