Introduction: Strategies for Preventing and Addressing Young Children’s Challenging Behavior in Early Childhood Settings

Data on high rates of suspension and expulsion in early childhood settings (Gilliam, 2005; Gilliam & Shahar, 2006; National Survey of Children’s Health, 2016), especially for young boys of color and young children with disabilities (U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights, 2014), have led to an urgent need to reconsider the use of punitive discipline strategies in the early years. Both early childhood mental health consultation (ECMHC) (Albritton et al., 2019; Gilliam & Shahar, 2006; Perry et al., 2010) and the use of policy (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services & U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights, 2014) are effective strategies for preventing and addressing young children’s challenging behavior. This paper describes a pilot project aimed at exploring the intersection of these practices using the Teaching and Guidance Policy Essentials Checklist (TAGPEC) as part of ECMHC.

The Teaching and Guidance Policy Essentials Checklist (TAGPEC)

The Statement on Expulsion and Suspension Policies in Early Childhood Settings (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services & U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights, 2014) proposes that high-quality discipline policies at the program level can help translate research into practice and address alarming rates of suspension and expulsion. Similarly, the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC), along with 34 agencies dedicated to the well-being of children and families, cite the need to create systems, policies, and practices that are data-informed and reduce disparities across race and gender to prevent, and ultimately eliminate, expulsions and suspensions in settings serving young children (NAEYC, 2014).

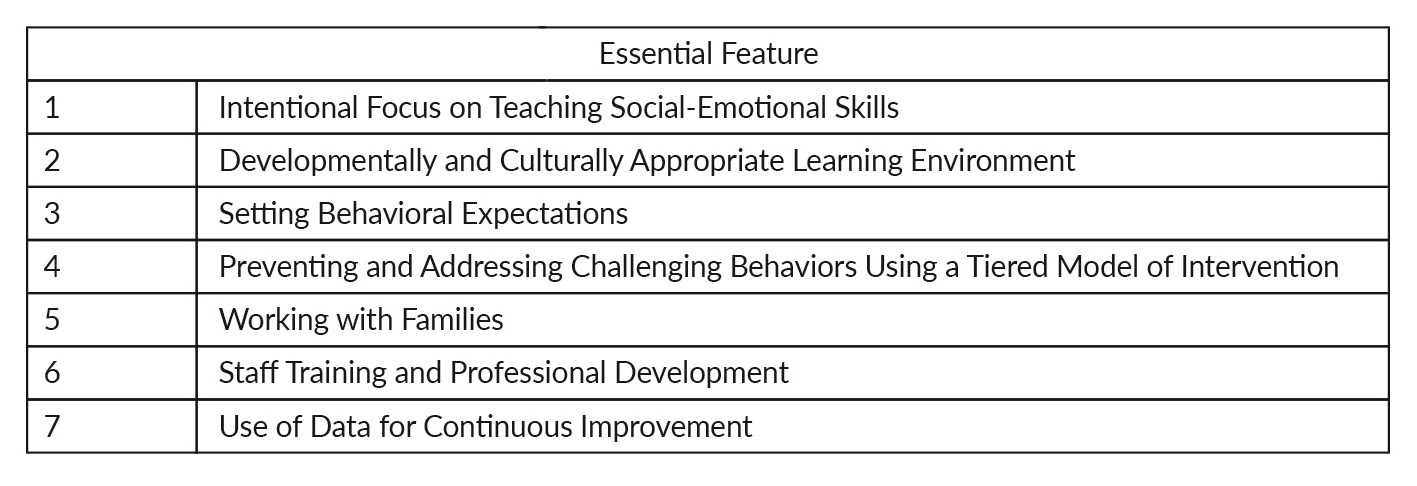

The TAGPEC is an easy-to-use 30-item checklist describing seven Essential Features of high-quality behavior-guidance policies for programs serving children from birth to eight years of age. The original version of the TAGPEC was developed by Longstreth, Brady, and Kay (2013) via an extensive review of the literature in the fields of general education, special education, early childhood education, early childhood special education, educational administration, and school psychology and it has been refined over the years as part of an ongoing research project (Garrity et al., 2015, 2016; Longstreth et al., 2013; Longstreth & Garrity, 2018; Garrity & Longstreth, 2020). Each item on the TAGPEC is rated along three dimensions: (a) a score of 0 is given if the item is not addressed in the policy, (b) a score of 1 is given if there is some evidence the item is addressed, and (c) score of 2 is given if the item is clearly addressed. The highest possible score a program can obtain on the TAGPEC is a 60, indicating that all seven Essential Features and corresponding 30 items are present. The 7 Essential Features of the TAGPEC are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Seven Essential Features of the TAGPEC.

Studies using the TAGPEC have found that early childhood behavior guidance policies seldom reflected evidence-based practices and often promoted a punitive rather than preventive approach to challenging behavior (Garrity et al., 2015; Garrity et al., 2017; Longstreth et al., 2013; Tamagni & Wilson, 2020). Programs scored particularly low on the Essential Features assessing the family-centered nature of early care, staff training and professional development, and the use of data for continuous improvement (Garrity et al., 2017). Research also indicates that alarmingly few programs address the importance of linguistically and culturally appropriate environments, experiences, and professional development, that ensures staff have a strong understanding of culture and diversity and engage in self-reflection to increase awareness of biases (Garrity & Longstreth, 2020).

ECMHC

ECMHC is an evidence-informed, multi-tiered intervention in which mental health professionals work with those who care for young children ages 0-6 to promote healthy social-emotional development and improve the ability of staff, families, programs, and systems to prevent, identify, treat, and reduce the impact of mental health problems (Cohen & Kaufmann, 2005; SAMHSA, 2014). Because ECMH consultation is designed to build the capacity of administrators and caregivers to manage challenging child behaviors, it adopts a systemic approach designed to improve programmatic functioning (Hunter et al., 2016). Research indicates that ECMHC reduces challenging behaviors and the risk of expulsion (Albritton et al., 2019; Gilliam & Shahar, 2006; Perry et al., 2010), while also improving the mental health of teachers (Brennan et al., 2008).

The Georgetown Model of ECMHC

The Georgetown model of ECMHC (Hunter et al., 2016) has been designed specifically for use in school settings and describes consultation at three levels: programmatic, classroom, and child and family. Child and family-level consultation addresses factors contributing to an individual child’s functioning and is often initiated because of concerns about a child’s behavior. At the classroom level, consultation is provided to teachers regarding how to best support the social and emotional development of all children. The goal of programmatic consultation is to build the program’s overall capacity to support social-emotional development by collaborating with and securing buy-in from school leaders and other support staff, which is essential to the success of ECMHC. Like the approach espoused by the TAGPEC, programmatic consultation adopts a systemic approach and seeks program-wide impact by focusing on multiple issues to improve overall program functioning. Programmatic consultation addresses issues related to philosophy, mission, program structure, policies, procedures, and professional development and requires administrators to consider how they support the mental health of young children and the overall social and emotional climate of the program.

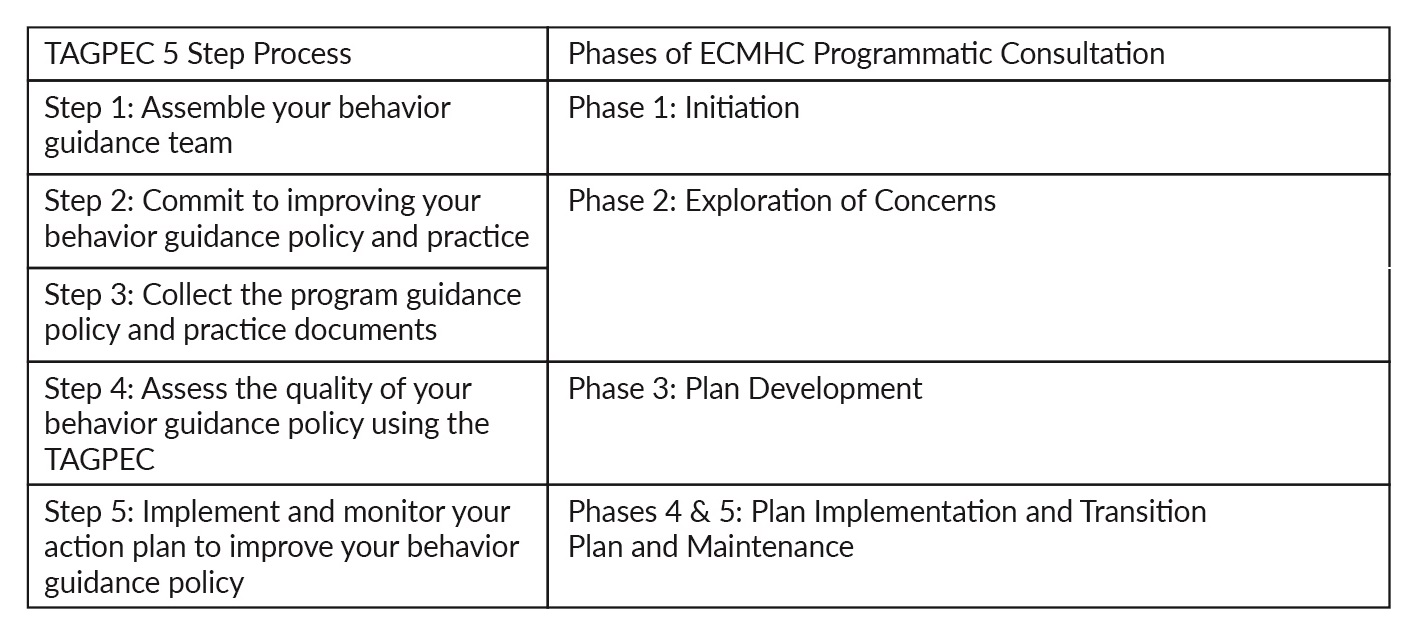

The seven Essential Features and 30 items of the TAGPEC address many of these areas and provide a systematic and measurable approach to support the facilitation of ECMHC at the programmatic level. In addition, the TAGPEC Five-Step Process for revising a behavior guidance policy (Longstreth & Garrity, 2018; Longstreth et al., in press) aligns with the phases of programmatic consultation described by the Georgetown model, as depicted in Table 2.

Table 2. Alignment of the TAGPEC 5 Step Process and the Phases of ECMHC Programmatic Consultation.

The Pilot Project: An overview

Aims

The purpose of this pilot study was to describe our experience using the TAGPEC to revise the discipline policy of two early childhood education (ECE) programs as part of ECMHC. Early childhood leaders play a critical role in shaping discipline policy and practice (Whitebrook et al., 2012). Early childhood programs that have been successful in implementing positive rather than punitive discipline are characterized by high teacher morale and cohesion, ample staffing and resources, and administrator support (Gray et al., 2017). In our experience, there has not been enough attention given to providing administrators with the training and support needed to help them understand the negative effects of punitive discipline and embrace positive and preventative climate-improving practices. Our goal with this study was to build strong leadership around climate and discipline that could, in turn, support consistent and evidence-based practices among all staff.

A brief description of the pilot program

In 2019, our state released guidance for the implementation of center-based ECMHC in subsidized childcare programs. Despite positive efforts on the part of the state to encourage the use of ECMHC, the funding formula proved to be a significant barrier to programs that did not already have an ECMHC program in place, preventing even highly motivated programs from participating. To address this issue and recognize the potential of ECMHC to improve the quality of ECE programs, the local County Office of Education partnered with First 5 California, a statewide agency committed to improving the lives of California’s young children and families, to provide supplemental funds to support a pilot project examining how ECMHC could be provided in subsidized ECE programs. The Georgetown model of ECMHC met all the criteria outlined by the state and was thus selected as the framework for ECMHC services provided in the pilot.

Context and Participants

The programmatic consultation described in this article was part of a larger ECMHC project. Consultation at the program level was conducted by the first and second authors, both of whom are early childhood faculty with expertise in social-emotional learning and educational leadership. The two early childhood programs that participated exemplify the wide variety of program types found in ECE. Both programs receive state funding and participate in the county’s Quality Rating Improvement System (QRIS), but are very different in terms of geographic location, child population, size, and administrative structure.

Site A is part of a school district known for its large refugee population, and the early childhood program includes state-funded preschool, transitional kindergarten, and early childhood special education. All programs fell under the auspices of an early childhood director, who was responsible for 21 state preschool classrooms located across 12 schools serving approximately 500 children. The program did not have a center or site directors at each location, but instead provided teachers with 10 hours a week outside of the classroom to complete administrative tasks.

Site B is in an area known for its large Spanish-speaking population and included two child development centers, one serving 80 infants and toddlers and another serving 186 preschoolers. A program director supervises two center directors responsible for day-to-day operations.

Both programs were selected for participation because they were rated a 4 or 5 on our state’s 5-tiered QRIS. Because the Georgetown model cites the importance of a program/school’s readiness for consultation, it was important to pilot this work with programs that had existing quality indicators in place, including administrative systems that could support ECMHC. An additional requirement was participation, through QRIS, in California’s Teaching Pyramid Framework (https://cainclusion.org/camap/map-project-resources/ca-teaching-pyramid/training) which is a series of five modules that address the key components of the Pyramid Model, a framework of evidence-based practices for promoting young children’s healthy social and emotional development (https://challengingbehavior.org/pyramid-model/overview/basics/).

The Pilot Project in Action across Two ECE Sites

TAGPEC Five-Step Process and ECMHC Programmatic Consultation

Step 1

The first step when using the TAGPEC to revise a program’s discipline policy is to assemble a behavior guidance team. This step corresponds to the initiation phase of programmatic consultation in which consultants build a relationship with key school administrators and support staff. The consultants reached out to the program directors, described the purpose of the programmatic consultation, and asked them to identify members of their behavior guidance team. At Site A, the behavior guidance team included the consultant, the program director, a program specialist, and a behavior intervention specialist. The behavior guidance team at Site B included the consultant, the program director, a developmental specialist, a developmental specialist assistant, and the site supervisors.

Step 2

The second step of the TAGPEC five-step process requires the team to commit to improving their discipline policy by examining their goals, values, strengths, and areas in need of improvement. This step corresponds with the exploration of concerns phase in the Georgetown model. The behavior guidance team completed a Strengths, Needs and Goals Interview, which was developed to help the team reflect and develop broad goals for programmatic change. Behavior Guidance Team Reflection Questions were also used to facilitate dialogue about the team’s beliefs and views about behavior guidance. The questions ask members of the team to reflect on their own experiences of discipline growing up and how these and other experiences (e.g., schooling) influenced their views about how to best address challenging behavior in the classroom.

Data gathered during this step indicated that there were similarities and differences across the two sites in terms of how they perceived their program’s strengths, barriers, and goals. Both programs identified the commitment of their staff and existing systems and policies as strengths and cited QRIS as a resource they relied on to improve program quality. Both teams specifically mentioned the Teaching Pyramid training as particularly helpful in increasing program capacity to prevent and address challenging behaviors. They also acknowledged that more work needed to be done to implement the model with fidelity.

Both sites described challenges related to a lack of time for professional development and data collection activities; both of which are important activities described by the Georgetown model of ECMHC and the TAGPEC. Funding, particularly the lack of money to hire substitutes to allow teachers to attend professional development and have time away from the children to complete paperwork, was described by both directors as a barrier. This challenge was especially acute for Site A because of district staffing patterns that rely on part-time teacher assistants to support lead teachers. Teaching assistants are unable to attend professional development activities, including the training that was provided as part of the programmatic consultation. An additional difference between the two programs was that the director at Site A wished for a greater understanding of early childhood development from the school district and more training and professional development that addressed this period. Importantly, Site B identified the need for resources related to special education services and described challenges in helping families access services and a need for targeted strategies to support children with disabilities. Conversely, because Site A was part of the local education agency, access to special education services was identified as a strength.

Step 3

Step 3 of the TAGPEC five-step process also encompasses the exploration of concerns phase of the Georgetown Model and requires programs to collect all existing information related to discipline. While many programs have a stand-alone behavior guidance policy, information about behavior guidance is often found in other documents, including parent and staff handbooks, incident reports, behavior support plan and referral forms, curriculum guides, or licensing documents. A critical part of revising a policy and strengthening the overall system is making sure all documents align and reflect the program’s philosophy, approach to behavior guidance, and goals for children’s learning and development.

At Site A, the parent handbook was quite extensive and had a Child Behavior section explaining program goals and what healthy social-emotional development and challenging behavior look like. It also described the Teaching Pyramid model of support and program-wide expectations: Be Safe, Be Healthy, Be Respectful, and Be Friendly. There was a description of procedures for working with children who demonstrate challenging behaviors and for the development of a behavior support plan. Elements of discipline were also found in other sections of the handbook, particularly those which described curriculum and parent engagement. The program also had a very comprehensive staff handbook that described program operating guidelines including policies and practices related to behavior guidance. The documents collected at Site B were a Prosocial Agreement and resources used to guide responses to challenging behavior, which included a developmental specialist referral form, an antecedent-behavior-consequences data collection tool, an observation form, and a behavior support intervention plan. Data collected during this step supported the results of the Strengths, Needs, and Goals Interview indicating that a strength of both programs was strong systems and policies.

Step 4

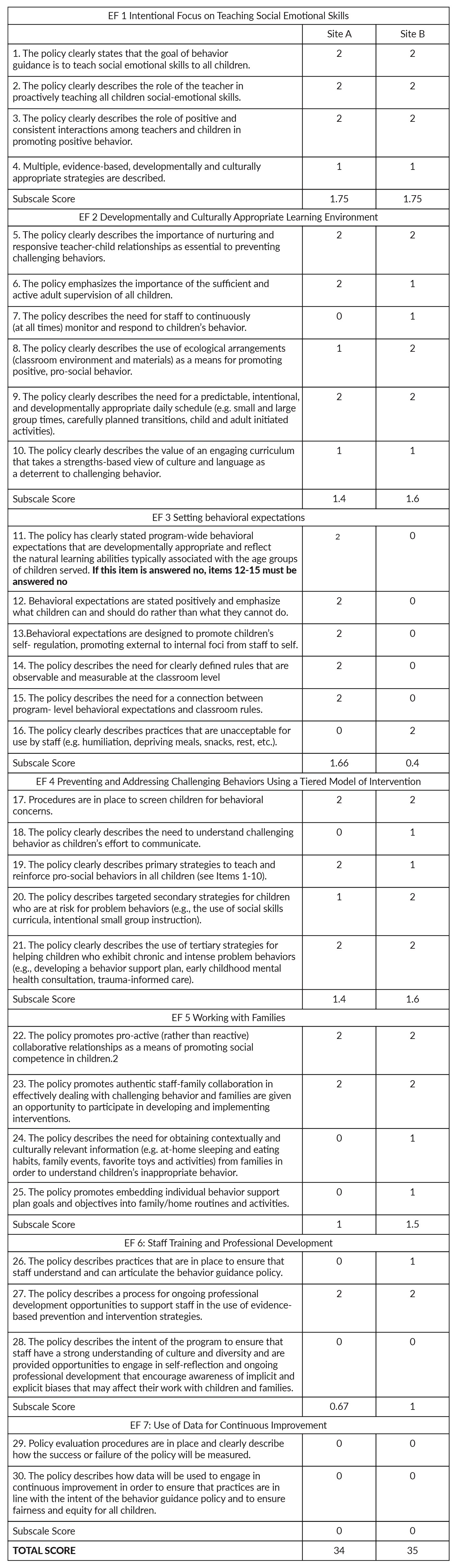

The fourth step of the TAGPEC process requires teams to carefully review all documents and assess the quality of their existing policy using the TAGPEC. This step corresponds to phase 3 of the Georgetown Model (plan development), which includes the review and assessment of data and collaborative plan formulation. At Site A, the consultant conducted an initial review of all documents, making notes on items that were not clear, or that were contradictory. She then met with the behavior guidance team and shared a preliminary document listing each essential feature, noting the strengths (items scored 2) and next steps (items scored as 1 or 0) and asked questions and gained additional clarity. At Site B, each member of the team individually reviewed all documents and scored the TAGPEC. The team then met with the consultant to come to a consensus about the ratings. TAGPEC results from both sites are presented in Table 3.

Once each team had reviewed and discussed the results of the TAGPEC, they developed goals for improving their policy. At Site A, the team decided to focus on ensuring the policy was consistent with all other documents, was more explicit about the strategies described by the Teaching Pyramid, and described processes for assessing children’s academic, behavioral, and social-emotional progress and implementing interventions. The action plan at Site B included a focus on developing wide behavioral expectations and a behavior matrix to support the consistent use of positive guidance strategies. An additional goal was to develop a consistent process for reporting challenging behaviors. Both sites sought to be more intentional about professional development and using data to check for implicit bias, as these were areas in which they received a score of zero on the TAGPEC.

Once behavior guidance teams set goals, they then worked to revise the policy. At Site A, the consultant completed the first draft of revisions based on the action plan developed with the team. The consultant and behavior guidance team provided back-and-forth updates and revisions via a shared google document. At Site B, the site supervisors and their staff met to develop a set of behavioral expectations, which were then used to guide the development of the behavior matrix. The consultant met with the behavior guidance team to discuss the policy revisions needed based on the TAGPEC results. This policy was shared with all team members on Google Drive so they could continue to provide suggestions and edits.

Step 5

The final step in the TAGPEC five-step process is to implement and monitor the action plan to improve your behavior guidance policy, which corresponds with phases 4 and 5 (plan implementation and transition plan and maintenance) of the Georgetown Model. Unfortunately, this step was not completed, as two months prior to the conclusion of the consultation, both programs were closed because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 3. Site A and Site B TAGPEC Scores.

Conclusion

The use of the TAGPEC supported the behavior guidance team to focus on multiple issues related to the overall quality of the program and make explicit changes to program policy to support program goals. The programs had differences in terms of their strengths and needs, and the early identification and understanding of these needs allowed the consultant to individualize the consultation process, a key feature of the Georgetown model. A collaborative, flexible, and individualized approach are also essential to the Georgetown model, and our findings suggest that the TAGPEC was a useful tool to support policy change, despite the significant contextual differences between Site A and B in terms of geographic location, administrative structure, and staffing.

As we reflect on the implementation of this project, it is important to acknowledge that our work represents the intersection of ECE and ECMHC in a unique way. This study was conducted by researchers at the Center for Excellence in Early Development (CEED) at San Diego State University, a transdisciplinary, research-based, training facility with a holistic approach to supporting early childhood development, mental health, and early childhood education. CEED was founded by the authors of this study to bridge ECE and early childhood mental health, and as such the researchers and clinicians who participated in this project share common goals, approaches, and philosophies. Project staff met regularly to address problems of practice, identify gaps and opportunities, and ensure that services were being implemented with fidelity. We believe that this approach reflects the intent of the Georgetown model and the TAGPEC’s goal of guiding programs to create an infrastructure that supports the social, emotional, and academic success of all children.

References

Albritton, K., Mathews, R. E., & Anhalt, K. (2019). Systematic review of early childhood mental health consultation: Implications for improving preschool discipline disproportionality. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 29(4), 444-472.

Brennan, E. M., Bradley, J. R., Allen, M. D., & Perry, D. F. (2008). The evidence base for mental health consultation in early childhood settings: Research synthesis addressing staff and program outcomes. Early Education and Development, 19(6), 982-1022.

Cohen, E., & Kaufmann, R. (2005). Early childhood mental health consultation. DHHS Pub. No. CMHS-SVP0151. Rockville, MD: Center for Mental Health Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Garrity, S., Longstreth, S., & Linder, L. (2017). An examination of the quality of behavior guidance policies in NAEYC- accredited early care and education programs. Topics in Early Childhood Education, 37(2), 94-106.

Garrity, S., Longstreth, S., Potter, N., & Staub, A. (2015). Using the Teaching and Guidance Policy Essentials Checklist to build and support effective early childhood systems, Early Childhood Education Journal, 1-8.

Gilliam, W. S. (2005). Prekindergarteners left behind: Expulsion rates in state prekindergarten systems. New York, NY: Foundation for Child Development.

Gilliam, W. S., & Shahar, G. (2006). Preschool and childcare expulsion and suspension: Rates and predictors in one state. Infants & Young Children, 19, 228–245.

Gray, A., Sirinides, P., Fink, R., Flack, A., DuBois, T., Morrison, K., & Hill, K. (2017). Discipline in context: suspension, climate, and PBIS in the School District of Philadelphia. Research Report (#RR 2017–4). Consortium for Policy Research in Education, University of Pennsylvania.

Hunter, A., Davis, A., Perry, D. F., & Jones, W. (2016). The Georgetown model of early childhood mental health consultation for school-based settings. Washington, DC: Center for Child and Human Development.

Longstreth, S., Brady, S., & Kay, A. (2013). Discipline policies in early childhood care and education programs: Building an infrastructure for social and academic success. Early Education and Development, 24, 253–271.

Longstreth, S., & Garrity, S. (2018). Effective discipline policies: How to create a system that supports young children’s social-emotional competence. Lewisville, NC: Gryphon House.

Longstreth, S., Garrity, S., & Linder, L. (in press). Developing and Implementing Effective Discipline Policies: A Practical Guide for Early Childhood Consultants, Coaches, and Leaders. Lewisville, NC: Gryphon House.

National Association for the Education of Young Children. (2014). Standing together against suspension & expulsion in early childhood. Available from https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/resources/topics/Standing%20Together.Joint%20Statement.FINAL_9_0.pdf

National Survey of Children’s Health. (2016). Available from https://www.childhealthdata.org/learn-about-the-nsch/NSCH.

Perry, D. F., Allen, M. D., Brennan, E. M., & Bradley, J. R. (2010). The evidence base for mental health consultation in early childhood settings: A research synthesis addressing children’s behavioral outcomes. Early Education and Development, 21(6), 795-824.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2014). Expert convening on infant and early childhood mental health consultation. Rockville, MD: SAMHSA Headquarters.

Tamagni, A. L., & Wilson, A. M. (2020). Discipline Policies and Preschool Special Education Students’ Personal-Social Skills. Journal of Educational Research and Practice, 10(1), 3.

U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights. (2014). Data snapshot: Early childhood education (Suspension Policies in Early Childhood Settings). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the U.S. Department of Education.

Authors

Garrity, Sarah,

San Diego State University, 5550 Campanile Dr. San Diego, CA 92182

sgarrity@sdsu.edu

Longstreth, Sascha,

San Diego State University, 5550 Campanile Dr. San Diego, CA 92182

slongstreth@sdsu.edu

Linder, Lisa,

San Diego State University, 5550 Campanile Dr. San Diego, CA 92182

llinder@sdsu.edu