Let me begin with a clinical case:

In the early 2000s, the HIV epidemic in South Africa was equivalent to a war zone in many communities, where the incidence was high and where the most vulnerable were being infected through no act of their own – the newborn infants.

Let me introduce you to Baby A and her mother.

Baby A was four months old when she presented to us in the primary health care clinic. She had been hospitalized with pneumonia due to being HIV+. While the young, first-time mother had been aware of her status, she was shocked that her baby was also infected. The father of the baby had left them, and the mother’s only support was a brother. She had not shared her diagnosis with anyone in her family (at that time, HIV was a taboo subject, especially among family members).

We followed this mother and her child until Baby A was three years old.

Baby A and her mother were exposed to many major psychosocial stressors. They suffered from a dangerous communicable disease: HIV. They endured hunger, financial insecurity, no or very limited family support, an absent father, and unemployment.

Despite all these major difficulties, she and baby A came through and did not just survive but thrive.

What were the protective factors, and what helped?

Perhaps it was Baby A’s ability to focus on her mother and her mother’s ability to smile at her and share pleasure. Both mother and Baby A were open and willing to seek help and be helped. They received support from the community structures that were in place and from the medical interventions that were starting to be administered at that time.

When Baby A was three years old, I received this report from our Developmental Paediatrician:

“Baby A is in good general health, has no hard neurology, and her mom has an excellent relationship with A and very good insight into her emotional and developmental needs. She is performing at or above her age equivalence for all the subscales, with the exception of some of the fine motor tasks….”

Given our context and setting, especially during those traumatic HIV years, this was a good outcome. We did not experience an actual war or natural catastrophe, but there are parallels between a deadly epidemic and the turbulences currently facing us.

I will return to these in the end.

I have deliberately started this presentation with a clinical case because we can move to meaningful research questions from the clinical case.

Over the course of this paper, I will trace some of the developmental lines in research that have emanated from making hypotheses to observations, as well as concrete, detailed research. And then I will come to the big question of WHAT NOW? given the dire state of the world that infants find themselves in.

Let us go to a hypothetical infant.

Our senses are open right from the very beginning, even before birth. We take in what surrounds us, it gets stored in our brains, our bodies, in our very being. We are sensitive to the fluid around us – it gets into our bodies.

When we come into the world, we can also see that we like human faces and friendly faces. We can hear the voices we’ve heard before, smell the milk we drink, and feel what’s in our mouths.

We are born to connect our senses to persons around us, particulalry to those who care for us. Those we know best, we attach to, and they become our life-giving other, our parents.

We are curious; we want to know the world. We enjoy stimuli that are not too loud, not too much, as we can easily feel flooded by our senses. For us, meeting what’s in the world is dramatic and emotional, so we cannot have too much of it.

BUT WHAT ARE YOU ADULTS DOING? DO YOU HAVE ANY IDEA HOW THE WORLD IS AFFECTING US?

I will cast the net wide before answering and look at two themes that are at the centre of Infant Mental Health (IMH): Development and Context.

I will trace a few of the many developments in the field of IMH and thereby honour some of our ancestors.

I will then try to look at what we should do, given this valuable data.

Development

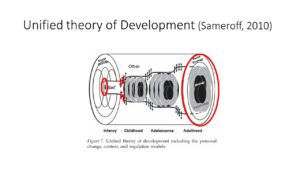

In one of his last great papers, Sameroff, in 2010, developed a Unified Theory that integrates nature and nurture. He employs a dialectical perspective, which shows the interconnectedness between the individual and the context (Sameroff, 2010).

The individual starts in a tiny, imperceptible way – the union of two gametes, and the individual ends when the adult body is dissolved. In this life course of about 80 years, infancy occupies the First 1000 Days – 2 years, plus 9 months of pregnancy. That is a tiny bit. So, why do we focus on it? Why is so much research, publications and theorizing, concentrated on this tiny bit of life?

The main reason has to do with the plasticity and openness of this time of life and the potential that it holds. At no other time in the human life span is there more rapid growth of the body and the brain, and with it, enormous developmental shifts take place.

Anna Freud referred to children’s progressive tendencies; it is their forward thrust, vitality, and will to live and move forward that signifies childhood and delights parents and families.

However, while the body will grow if given sufficient food and shelter, the brain and the mind need more; they need relationships with others. Food, shelter, and relationships with others are fundamental; they are the “contexts” surrounding this tiny bit of early life.

The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) field is gaining increasing traction in global research and writing. Its hypothesis states that environmental factors during critical periods of development have a lifelong effect on biological systems. Such as the central nervous system, the neuroendocrine system, and the immune system. The vulnerability or sensitivity is highest when the organ systems are developing and still immature (Penkler, Hanson, Biesma & Müller, 2019).

The impact of DOHaD research raises our awareness of social contexts and their importance in determining development across the lifespan. We all have enormous social and political responsibility towards those who need it most, as they will be the adults of the future.

The most devastating sector of the current global crises is the fate that has befallen infants. They have no voice; they can only cry if they still have life in them, or they drop into silence – of frozenness or death.

Can we bear to hear what they would say to us? Campbell Paul (Past President of WAIMH) is an expert in giving infants a voice in interpreting their behaviour. His fundamental approach is: What can the infants tell us? Let that be our guiding principle.

Let us try to imagine what they might say, and let us at the same time be informed of the research that proves what they say.

Before entering into the world

So, we are going back to the beginning of the First 1000 Days—to the tiny bit of a human being—and imagining what this small being is telling us. But this is not just fantasy, idealizing, or sentimental talk. Science corroborates what psychoanalysts have imagined long ago.

Observing fetuses while in utero via ultrasound (Piontelli, 1992)

We owe much to Piontelli’s work in the early 1990’s. Following the Infant Observation model, she started observing fetuses while in utero via ultrasound examinations. She found continuity in aspects of prenatal and postnatal life, with fetuses showing characteristics that would also be observable after birth. She states:

What I think my findings do suggest is that the interplay between ‘nature’ and ‘nurture’ begins much earlier than is usually thought, and that certain pre-natal experiences may have a profound emotional effect on the child, especially if these pre-natal events are reinforced by post-natal experiences. (Piontelli, 1992, p. 1)

Measuring fetal behavioural responses to external stimuli (Marx & Nagy, 2015)

Twenty-three years later, we have a study by Marx and Nagy (Marx & Nagy, 2015) which sets out to measure fetal behavioural responses to external stimuli. Fetal movements of arms, head, mouth, arms crossing, hands touching the body, and yawing were the responses that were coded. Maternal touch of the abdomen was a powerful stimulus, with the fetuses displaying more movements of their arms, head, and mouth. The older fetuses in the third trimester responded more than younger fetuses. The maternal voice led to decreased fetal heart rate, which suggests behavioural quieting in response to the mother’s voice.

The findings of these two research projects are the result of direct observations. The first one relies on careful descriptions of fetal behaviour based on the IO model. The second employs more sophisticated ultrasound recording that enables the coding of fetal movements in response to outer stimuli.

Transdisciplinary brain research (Frohlich et al., 2023)

The third piece of research I want to introduce is that by Frohlich and colleagues (2023).

From the authorship alone, one can see how the research is becoming increasingly complex: from single authors to two authors and now to ten authors from multiple centres on different continents. Direct observation is replaced by measurements, which are then translated into images of the brain and graphs.

In essence, this large group of researchers is trying to demonstrate concretely the answer to the difficult question of ‘when does consciousness emerge?’ They set out to look at functional brain data from human fetuses using complicated technical methods.

The measurement of sensory pertubational complexity – means that if one of the senses is stimulated, such as the auditory or visual, then a complex ‘disturbance’ is seen on the screens of the various devices that they use. One of the findings is that a mismatch in response to sound frequency was visible as early as 28 weeks of gestation. This means fetuses respond to an unexpected sound at this early gestational age. Evidence suggests that there is intrinsic connectivity within the motor, visual, auditory, and thalamic networks.

So, these are concrete data and findings that can be seen and measured even before birth.

The infant in the world

Let us now move to the infant in the world!

Let us continue the theme of cross-modal perception. It is this ability that infants have that fascinated me so much when I entered this field.

In 1979, Andrew Meltzoff and Richard Borton published their simple but elegant experiment in Nature (Meltzoff & Borton, 1979).

Two different pacifiers were placed in the mouths of infants whose eyes were covered. They were then taken out and shown to the infants.

Infants fixated on the shape matching the tactile stimulus of the pacifier.

Their conclusion was

… neonates are already able to detect tactual-visual correspondences, thereby demonstrating an impressive degree of intermodal unity. (Meltzoff & Borton, 1979, p. 404)

This automatically brings us to Daniel Stern, whose writings in the 1980s put many of us on the path of infant mental health. There is so much that could be said about this man—a clinician, psychoanalyst, and researcher. It is this unique combination, in fact, his intermodal transfer between these disciplines, that made his writings so compelling.

Here, I only want to focus on what he wrote about when he described the sense of an emergent self—that early phase from birth to 2 months. He asks,

“How might the infant experience the social world during this initial period?” (Stern, 1985, p. 37).

He answers the question in this way.

Many separate experiences exist, with what for the infant may be exquisite clarity and vividness….When the diverse experiences are in some way yoked…the infant experiences the emergence of organization… The sense of an emergent self thus includes two components: the products of forming relations between isolated experiences and the process. (Stern, 1985, p. 46-47)

He gives many examples of this ‘amodal perception’ in different modalities, including touch and vision (as just described), light intensity and sound intensity, and the correspondence between an auditory temporal pattern and a similar visually presented temporal pattern.

This means that infants can “take information received in one sensory modality and somehow translate it into another sensory modality. We do not know how they accomplish this task” (Stern, 1985, p. 51).

Well, perhaps we are getting closer to answering Stern’s question by looking at some recent multi-centre research by Mahshid Fouladivanda and her team. The 2021 paper, published in the Journal of Neural Engineering, tells us how far this field has moved into the electronic neuroimaging domain. In fact, it is impossible to really understand the methodology because it is so technical. But we can get to the gist of it (Fouladivanda et al., 2021).

Their study aimed to explore brain networks in neonates through functional magnetic resonance images. There is a rapid change in brain morphology and white matter pathways, particularly during the first few weeks after birth. They modelled brain regions that serve as nodes and are interconnected via white matter pathways.

It may well be that these visible, measurable developments in the infant brain form the basis of the efficiency of amodal perception.

So much for development that goes on within the infant.

Let us move to “context”.

The early ‘context’ of the fetus and infant

So, what about the caregiver’s influence? “There is no such thing as a baby, only a baby with its mother” is the perennial quote from Winnicott. Ever since the time of Hippocrates, clinicians have been aware of the association between the postpartum period and depression (Duquaine-Watson, 2022).

I am mindful of current thinking that questions the primacy placed on the role of the mother for the care of her infant, thereby bypassing the responsibility that other persons and institutions have, such as the fathers and the state, AND also bypassing the fact that in many cultures in the world, infant care is not exclusively the ambit of the mother.

However, pregnancy and the early months of life depend on the mother’s well-being. She physically carries and feeds this infant.

Increasingly, the research is focussing on prenatal exposure to maternal stress and the risk it poses for mental health problems in later life. The fetal programming and the DOHaD hypotheses mentioned earlier state that during sensitive periods of development, environmental factors, such as exposure to hunger and exposure to stress, affect the organization of the biological systems, with long-lasting effects (Van den Bergh et al., 2020).

The results of this review on the effects of prenatal exposure to maternal stress suggest that pregnant women and their unborn children ought to be recognized as vulnerable populations and protected accordingly from undue hardship and distress. (Van den Bergh et al., 2020, p. 58)

BUT what happens when there are wars, displacements, hunger, earthquakes and floods?

When the context is so traumatic that development is affected and even disrupted?

My own clinical work showed how the maternal/family environment impacts on caregiver attunement and sensitivity and how that in turn, can impact on the feeding relationship, with potential serious consequences for the child’s ongoing physical and mental development. Baby A and her mother are but one example.

What happens when the emergent self is overwhelmed with sensations that cannot be linked or yoked, that do not make sense, that defy inherent expectations?

What happens when suddenly there is no known ‘other’, no attachment figure who the infant can see, feel, and hear?

Perhaps we can most clearly see this in this recording of the original Spitz film of infants who were separated from their mothers.

I have given an overview of research on some of the developments in early pre- and postnatal life. I hope to have shown how early clinical observations have led to focused and specific research and how this is ongoing and becoming increasingly detailed and concrete. Where have we come to? What have we done with this knowledge?

WHAT WOULD INFANTS SAY TO US?

“STOP IT WHERE YOU CAN!”

“The history of childhood is a nightmare from which we have only recently begun to awaken” (de Mause, 1974), and in fact, are going back into.

What are we not hearing? Why are we not listening? I turn to Dan Stern’s plea to the WAIMH Yokohama Conference in August 2008.

He delivered a plenary address, “Perspectives on Infant Mental Health”, and focussed on the state of research generally speaking and in particular as it relates to infant mental health. It was an erudite, provocative ‘call to action’, which I will never forget.

Stern challenged many sacredly held beliefs about the reductionist approach to research, which breaks up the whole into tiny pieces—the ‘higher order’ which the infant is capable of is being dissected and ultimately rendered meaningless; he challenged evidence-based medicine, stating that we understand enough to know that in the field of infant mental health, it is time to do something else, to redress that which has been lost.

What has been lost is what babies need, namely mothering [parenting]. We have more than enough evidence for this. He appealed to ‘go big’, to hold concerts with rock stars, and mobilize the people so that the politicians may realize that the vote, the power, lies with women and men who wish to reclaim the importance of parenting.

I am not sure that rock concerts are enough to help us today.

Infants have no power. They do not have the vote. Whatever voice they have is not translated into adult language, and whatever voice they do have can easily be ignored or silenced.

But underneath this, there is a deeper layer – namely, that there has been, in the history of childhood, a collective denial of infant sentience (Bain, 2020).

In other words, the genuine realization that infants have an awareness that they have feelings, even if they can’t articulate these as yet. But this is perhaps too frightening to contemplate for the adult world – it takes us back to our own infancy and early childhood years, plus it places an enormous responsibility on us as adult human beings. Perhaps it is this that we, as a collective human group, are defending against – denying, repressing, or splitting off.

What can we do?

It is WAIMH’s stated aim to “…encourage the realization that infancy is a sensitive period in the psychosocial development of individuals” (WAIMH Bylaws, 2008, Article II, Section 1) – which is putting it rather mildly.

The Position Paper on Infant Rights states

In spite of the existence of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, many societies around the globe still pay insufficient attention to infants, especially in times of stress and trauma (WAIMH, 2016).

You can access this paper in WAIMH Perspectives in Infant Mental Health here: PositionPaperRightsInfants_-May_13_2016_1-2_Perspectives_IMH_corr.pdf (waimh.org)

We have a position statement on Infants in War (Keren, Abdallah, & Tyano, 2019). This paper, published by Wiley in the Infant Mental Health Journal, is open-source. You can access the paper here: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/imhj.21813

We have the Infant Rights document. There is a working group on Ethics in IMH, and we have our Global Crises Working Group.

I am hoping that we will set the process in motion to engage with the World Health Organization formally, but this will take time as the wheels of such global organizations turn slowly.

While we should think big, perhaps the only workable, doable way forward is through small steps—such as supporting and collaborating with the organization CARE Palestine and walking with them, as our Crises Working Group is trying to do.

We need direct contact with key people—we need to share with them the value of ‘little’ gestures, as Hisako Watanabe so eloquently explains. We need to share and let them know, for example, about the research done on Shared Pleasure by our colleagues Kaija Puura and Anusha Lachman, the value of having moments of reflection, of being with the infant despite the turmoil in the outside world.

Baby A and her mother gave us a glimpse into what can be done in the intimate space between caregivers and infants. What can scaffold and hold them and enable pleasure to be shared between them? We know about the protective function this offers.

We need our affiliates to liaise with colleagues on the ground and on the front line.

And, they need to know that there is an umbrella organization – we in WAIMH – that is ready to provide support, reflective space and advice.

I want to end with a worldview that in Africa has great meaning; that is Ubuntu….the concept that a person is a person because of persons – or, put in another way, I am because you are (Berg, 2012). It is the most succinct description of the centrality of relationships in human existence, a central theme for Infant Mental Health.

Ubuntu also means that if I have enough of something, I should share it with my neighbour. In a world that is so unequal in terms of resources and opportunities for infants to not only survive but thrive, we need to give of what we have, and that is our capacity to listen, to have empathy, and to enable thinking and reflection.

How to translate this human capacity, our Ubuntu, into actions, is the task I would like to set for ourselves as a world association for the next four years.

My final concluding remark is a part from a poem which a psychoanalyst and friend, Valerie Sinason, wrote in April of this year:

“What chances do living children have?

But the Esperanto of a single child’s cry

Counts more than any blood-soaked flag.”

References

Bain, K. (2020). The challenge to prioritize infant mental health in South Africa. South African Journal of Psychology, 50(2), 207–217. https://doi.org/10.1177/0081246319883582

Berg, A. (2012). Connecting with South Africa – cultural communication and understanding. College Station.

de Mause, L. (1974). The History of Childhood – the evolution of parent-child relationships as a factor in history. London: The Psychohistory Press.

Duquaine-Watson, J. M. (2022). Postpartum Depression. Women’s Health: Understanding Issues and Influences: Volume 1-2, 2(6), 520–522.

Fouladivanda, M., Kazemi, K., Makki, M., Khalilian, M., Danyali, H., Gervain, J., & Aarabi, A. (2021). Multi-scale structural rich-club organization of the brain in full-term newborns: A combined DWI and fMRI study. Journal of Neural Engineering, 18(4). https://doi.org/10.1088/1741-2552/abfd46

Keren, M., Abdallah, G., & Tyano, S. (2019). WAIMH position paper: Infants’ rights in wartime. Infant Mental Health Journal, 40(6), 763–767. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21813

Marx, V., & Nagy, E. (2015). Fetal behavioural responses to maternal voice and touch. PLoS ONE, 10(6). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0129118

Meltzoff, A. N., & Borton, R. W. (1979). Intermodal matching by human neonates. Nature, 282(5737), 403–404.

Penkler, M., Hanson, M., Biesma, R., & Müller, R. (2019). DOHaD in science and society: Emergent opportunities and novel responsibilities. Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease, 10(3), 268–273. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2040174418000892

Piontelli, A. (1992). From Fetus to Child. London: Routledge.

Sameroff, A. (2010). A unified theory of development: a dialectic integration of nature and nurture. Child Development. United States. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01378.x

Stern, D. (1985). The interpersonal world of the infant. New York: Basic Books.

Van den Bergh, B. R. H., van den Heuvel, M. I., Lahti, M., Braeken, M., de Rooij, S. R., Entringer, S., … Schwab, M. (2020). Prenatal developmental origins of behavior and mental health: The influence of maternal stress in pregnancy. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 117(November 2016), 26–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.07.003

WAIMH (2008). WAIMH Bylaws (February 10, 2008). www.waimh.org

WAIMH (2016). WAIMH Position Paper on the Rights of Infants. Perspectives in Infant Mental Health, Vol 24, No. 1-2, Winter-Spring, 2016.

Authors

Astrid Berg, WAIMH President

Emerita A/Professor, University of Cape Town

A/Professor Extraordinary, Stellenbosch University

South Africa