Abstract

There is limited research on the experiences and reflections of coaches of early childhood home visitors (HVs). This article examines the context and experiences of my work as an early childhood home visiting coach in the U.S. in promoting a coaching philosophy and approach to target HVs’ regulation and practice. In this autoethnographic account, I share and analyze my journal entries in light of an infant-parent mental health fellowship and related experiences. I also compiled stories about my experiences receiving support, such as reflective supervision and mentorship, to support my coaching work. Finally, I include interviews with HVs to promote my reflexivity. This work examines adult regulation and educational and therapeutic transformation by describing the critical need and approaches for fostering reflective coaching among early childhood HVs. My methods revealed connections: connections between the infant mental health research and my own experiences, ways that I connected to mentors and coaches, and ways that HVs I coached made connections to me and to the families they serve. Coaching is a process of making multilayered connections that require deeply reflective and self-regulating work like what is typical of autoethnographic self-reflection.

Keywords: infant mental health informed coaching; early childhood home visitors; regulation; practice; processes

Key Findings:

- The first author’s statement about the difficulty and vulnerability of taking on autoethnographic narrative methods was meaningful and essential to autoethnographic work–especially when considering what taking those vulnerability risks can teach the field about the power of connections for HVs and coaching.

- The study integrated concepts from the Infant-Parent Mental Health Fellowship (IPMHF), such as attachment, regulation, and reflective functioning, into the coaching model. These concepts were used to inform and enhance the coaching practices and to foster a collaborative and supportive environment that values the HVs’ experiences and expertise. This approach aimed to create a space where HVs could reflect on their regulation and practices and develop new strategies to support families.

- The importance of a semi-structured, reflective coaching approach that incorporates principles of regulation, reflective functioning, and infant mental health lies in its ability to support the practice and well-being of home visitors (HVs).

On Promoting Reflective Coaching for Home Visitors’ Regulation and Practice: An Autoethnographic Account

Positionality Narrative

While I was completing a 15-month transdisciplinary intensive Infant-Parent Mental Health Fellowship (IPMHF) in the United States, one of the luminaries or speakers referred to Weisner’s (1997) article about how ethnography is a powerful method to understand human development. The luminary said ethnography is particularly well-suited to understanding infant-parent mental health. Ethnographic work can create findings that matter to understanding the adaptive endeavors of individuals and communities (Weisner, 1997). I searched library databases and the grey literature for ethnographies about coaching. I found a study about autoethnography to understand team coaching practice (James, 2015). For my capstone project in my IPMHF, I wanted to understand more about coaching home visitors (HVs) individually. I consider myself both a researcher and a practitioner in coaching home visitors. I know “auto” means self, but autoethnography was new to me. I share this not to become the avatar for coaching home visitors; rather, there may be something in my positionality narrative that resonates with the readership. Autoethnographic methods were not only new to me, but they were also uncomfortable—such methods are the opposite of what I was trained to do. As an undergraduate and master’s student, I manipulated variables to determine toddlers’ and preschoolers’ language abilities and acquisition (Walsh & Chapdelaine, 2004; Walsh & Blewitt, 2006). As a doctoral student, I read Bronefenbrenner (1977) and gained an appreciation for contextual approaches, and as a professor, I gained an appreciation for qualitative approaches, capturing lived experiences, and relationship-based work.

These more vulnerable, more personal methods allow for exploring coaching processes and strategies, particularly when there is only a small body of literature about coaching home visitors (see Walsh et al., 2023, Walsh et al., 2022, Walsh et al., 2021; West et al., 2024). Reflection and reflective practice, or focusing on complex experiences that tend to elicit uncertainty and emotional responses, are essential to Infant Mental Health (Tobin et al., 2024). I share my narrative reflection, which may allow readers to resonate with my experiences and wonder what they might learn about my approach to documenting and reflecting on what coaching home visitors can offer. I have uncovered that the “so what?”when reflecting and explaining upon my work is that coaching fosters multilayered connections between theory, practice, coaches, coachee (home visitor-as-coachee or client), and families.

Coaching Home Visitors

Coaching is a strategy that early childhood (EC) home visiting programs use to reduce stressors and support HVs (National Home Visting Resource Center, 2020). Coaching is an individualized, strengths-based process fostered by a collaborative partnership between the coach and HVs-as-coachees to help HVs create and attain goals (Walsh et al., 2023). Despite multiple calls for EC HV coaching (McLeod et al., 2021; Walsh et al., 2022), more research is needed to better understand coaches and coaching approaches. To help coaching HVs advance in research and practice, descriptions of coaching processes (Walsh et al., 2022), such as narratives of the situated individual(s) or coach and coachees, are needed (James, 2015; Kempster & Iszatt-White, 2013). Autoethnographic narratives about coaching can provide a sense of truth about an experience and insight into complex processes and practices (Kempster & Iszatt-White, 2013). This article seeks to support (1) a coaching program’s conceptualization to bolster HVs’ efforts and (2) a coach’s and HVs’ comprehension of effective coaching and lived experiences.

HVs should be coached in a way that honors the parallel process. For example, HVs who experience empathy from the coach and joint planning in coaching can use those competencies when coaching families. In turn, parents may provide support by being responsive to their children (Pawl & St. John, 1998; Walsh et al., 2023). Translating coaching strengths, ideas, and strategies into HVs’ work with at-risk families can be challenging, given their work in changing home environments where they have minimal control and encounter unexpected stressful situations, necessitating support for transferability (Walsh et al., 2023). The defining features of HV coaching—collaborative partnerships, individualized HV goals, action planning, observation and focused observation, reflection, strengths-based feedback, on-demand or regular sessions, and the recognition that the HV is a coachee and family coach (Walsh et al., 2022)—empower the HV to take charge of their professional development (PD). Coaching is distinct from reflective supervision (RS) and will be discussed below.

Coaching: Different From and in Addition to RS

RS married with IMH is known as Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health (IECMH) reflective supervision/consultation (RS/C) and is a relationship-based practice that is essential to supporting professionals (Tobin et al., 2024). There is some disagreement about the empirical definition of RS and limited literature on RS in HV (West et al., 2022). However, RS can be measured by the Reflective Interaction Observation Scale (RIOS; Meuwissen & Watson, 2022). A new RS self-report measure is being developed to elucidate how it is practiced (Denmark et al., 2024). Similarly, while effective HV coaching remains underutilized and under-studied, there is agreement that coaching is an essential component of PD and matters for HVs’ practice and the success of HV programs (Walsh et al., 2022). RS is a nurturing, relationship-centered process that provides a safe and open space for HVs to discuss how their work with families affects them (Haring & Rau, 2024). HVs can share their feelings, perceptions, inner awareness, biases, and beliefs related to their experiences and the families they serve. However, there is always an inherent power differential between supervisors and HVs, potentially impacting RS’s collaborative nature (Walsh et al., 2023).

While coaching includes a partnership focused on goals set by the HV in collaboration with the coach (Head Start ECLKS, 2022; Haring & Rau, 2024), RS is collaborative in its focus on a shared purpose. In the coaching process, the HV takes on the roles of collaborator and driver. Coaches may have different education and experiences than HVs, and it is recommended that coaches understand reflection, outcomes, and parallel processes (Walsh et al., 2022). Coaches may also have experience with video recording home visits and HV observation scales (Walsh et al., 2023; Walsh et al., 2022). The coach observes the HV’s practice based on the individualized goals and action plans created by both parties. This approach ensures no surprises for the HV during the coach’s observation. Regular RS is recommended, while coaching is more flexible, on-demand, and time-limited (Haring & Rau, 2024).

Coaching Processes for a Vulnerable Workforce

In addition to promoting practice, the HV field needs coaching that supports HV well-being, given that many HV programs support family well-being as an outcome (Walsh et al., 2022) and because HVs are regularly exposed to trauma while fulfilling their duties. Early Head Start (EHS) HVs represent a particularly vulnerable workforce, often receiving less training, organizational support, and compensation than other people-oriented professions (Mavridis et al., 2019; West et al., 2018). Reports on EHS HVs’ coaching reveal discomfort from integrating coaching ideals into support practices. The emotional toll of HVs’ work compounds this methodological gap, frequently leading to secondary stress, trauma, compassion fatigue, and burnout (Alitz et al., 2018; Begic et al., 2019). One EHS HV coach particpant in Walsh et al.’s (in review) study shared, “I’ve had several of what I call crying sessions,” describing HVs’ stress with a practice-based model. This participant’s account of how coaching has not prioritized EHS HVs’ well-being resonated with me and other HVs, and inspired us to share these experiences and lived lessons with other coaches. Writing from and through personal experiences in tandem with and in the context of the experiences of others can create epiphanies, which are transformative moments and realizations that can alter the course of something (Adams et al., 2015). Autoethnographies start where we are, and I, like others in the field, want coaching to be a positive and transformative space. We need accounts of implementation fidelity but we also need narratives to understand how to get there. This article aims to share these experiences and lived lessons with other coaches.

Coaching can learn from autoethnography. Hallmarks of quality autoethnography include mindful attentiveness, noticing, introspection, deep and active listening, examining sense data perceptions, self-reflexivity, and awareness (Poulos, 2021). Coaching may influence HVs’ attunement practices, well-being, thinking, regulation, emotional responses, reflection, and perspectives and strengthen their efficacy by providing a safe, protective space that values the HV as an expert and an equal or a collaborator. This article represents one effort to describe and explain through autoethnographic methods how these processes and mechanisms of coaching influence HVs.

Method

The Context for IPMHF and Coaching Home Visitors

As a professor, I work at a university with an EC home visiting program, and my primary role in the program is as a coach. The EHS program uses Parents as Teachers (PAT) as the curriculum. I completed model training in PAT and recently finished a 15-month transdisciplinary intensive Infant-Parent Mental Health Fellowship (IPMHF). The fellowship values “inter-disciplinary training based on a practice model encompassing promotion, prevention, early intervention, pan-disciplinary services, and discipline-specific services” (The Regents of the University of California, Davis., n.d., Napa IPMHF section). Model training and the IPMHF have shaped my current approach to coaching.

My coaching journey started with five HVs in 2017 during a year-long sabbatical. Coaching HVs was in the nascent stages then. Allen’s (2016) family life coaching and literature from the EC field (Artman-Meeker et al., 2015; Elek & Page, 2018; Isner et al., 2011; Rush & Shelden, 2020) formed the first iteration of my coaching philosophy. Allen’s (2016) family life coaching is a skill subsumed within the Certified Family Life Educator (CFLE) credential, and I have been a CFLE since 2009. The first iterations of my coaching philosophy, which emphasized dignity and respect for HVs through a collaborative process and ideas about processes and how to promote goal setting and attainment, helped me find my identity as a coach of HVs and informed my coaching approach.

After my first coaching experience, my coaching philosophy shifted as I reflected on my coaching work with my home-visiting research colleagues. Analysis of my coaching transcripts revealed that HVs achieved their goals and demonstrated reflective thinking to promote goal setting (Walsh et al., 2021). We examined the current state of coaching literature in the EC home visiting field and compiled themes that research and practice agendas should consider (Walsh et al., 2022). For instance, HVs have the dual role of HV-as-coachee and as a family coach. We created a published conceptualization that underscores this complexity of coaching in the HV space (Walsh et al., 2023).

About 7 years after my original coaching work and contribution to the EC home visiting literature (Walsh et al., 2022) and conceptualization of coaching (Walsh et al., 2023), I worked with my department chair and the home visiting program to change my academic role statement to include individual coaching of seven HVs once or twice a month at my university’s EC home visiting program. The catalyst for this change was a 2023–2024 IPMHF. I completed the 15-month IPMHF in April 2024. I have used concepts and luminaries from the infant mental health field to further inform my coaching approach to working with HVs. This coaching model integrates concepts such as the neurosequential model of reflection and stress response (NMRS) continuum (Brandt, 2023; Brandt & Perry, 2024); rhythm, regulation, relation, and reasoning or the neurosequential model of therapeutics (NMT; Neurosequential Network, n.d.; Perry, 2009, 2023). Tomlin and Vieweg’s (2024) PAUSE framework values perspective-taking and thoughtful solution finding by integrating relational skills and reflective practice to help home visitors navigate complex situations by encouraging HVs to pause, reflect, and respond thoughtfully. Brandt and Perry’s reflective process approach is equally thoughtful to Tomlin and Vieweg’s framework. Brandt and Perry’s framework provides rationale for the “regulate, relate, reason” approach based on functional levels of the human brain (brainstem, diencephalon, limbic system, and neocortex). My coaching approach also values attachment and the Circle of Security (Circle of Security International, 2018; Hoffman et al., 2006); understanding mental states and reflective functioning (Brandt & Perry, 2024; Fonagy & Target, 2005; Slade, 2005); coaching as a necessary space (Grimes, 2023); and my participation in RS (individual and group) and consultation/mentoring to strengthen my coaching processes.

In the second half of my IPMHF, I strongly desired to learn more about coaching HVs through descriptive methods. To help me share my narrative, I took an autoethnography class at a university.

Research Design: Autoethnography

By interweaving autoethnography (Adams et al., 2022; Bochner, 2012; Poulos, 2013), concepts from the infant mental health field, and interviews with HVs, I will share coaching experiences to promote HVs’ dual regulation and practice. This qualitative approach is about writing from and through experiences in tandem with and in the context of the experiences of others (Adams et al., 2015). This approach will foreground my experiences and reflections (auto), delve into cultural practices, identities, and beliefs (“ethno”), and employ a narrative voice and evocative representations (“graphy”; Adams et al., 2022). Throughout this article, I integrate three types of data sources:

- Journal entries in light of an IPMHF and related experiences that have influenced the coaching approach,

- Narratives based on notes that captured my experiences receiving RS and consultation to support my coaching work, and

- Interviews with HVs to supplement my autoethnographic work and promote my reflexivity.

For this third data source, I interviewed HVs enrolled in coaching (HV-as-coachee) to supplement my autoethnographic data from my experience as an HV coach. Interviews in autoethnography can help generate new information, validate personal data, and gain others’ perspectives (Chang, 2016; Marvasti, 2006). I interviewed three HVs enrolled in coaching via Zoom post-IRB approval. Before data collection, I created 11 interview questions, reviewed by a qualitative researcher not affiliated with this work, and I made minor revisions to the semi-structured guide. Sample questions include: (a) How, if at all, does coaching promote your well-being and regulation? and (b) What, if anything, could strengthen HV coaching in your program? Although I created the questions in advance, I used the flow of the conversation more so than verbatim adherence to the guide (Patten & Newhart, 2018). I analyzed the transcripts using reflexive thematic analysis, with an experiential orientation, utilizing an inductive approach (Braun & Clarke, 2022) based on the hermeneutics of empathy (Braun & Clarke, 2022; Willig, 2014). I read the dataset as a whole and coded the data for singular ideas, and I identified 29 codes. Next, I looked for patterns across codes and the dataset, the foundation for candidate themes. I used reflexivity regarding the interview data, including reflection on my influence as the researcher on shared knowledge (Braun & Clarke, 2022), as well as my experiences as a coach, as documented in my journal entries. I shared the findings with the HVs, and I asked the HVs to consider them within the context of their experiences. HVs suggested no changes to the findings.

Results

Using IPMH Research to Inform Coaching of HVs (Part 1)

First, journal entries for this inquiry reflected luminaries and concepts gleaned from my IPMHF and related experiences, such as becoming a Circle of Security Parenting (COSP) facilitator (Circle of Security International, 2018; Hoffman et al., 2006). There were three areas of journal entries: attachment, reflective functioning, and regulation; these and their related constructs were selected because they are foundational IPMH concepts applicable to most clinical and non-clinical settings, such as coaching. These are the areas I wondered about the most in my work as a coach. If HVs had experiences with these in coaching, there could be parallel impacts on parents’ influence on their infants and young children. The left-hand column below includes citations highlighting IPMHF luminaries and their scholarly research when applicable. The right-hand column includes excerpts from my reflective journal entries. Please refer to Tables 1 and 2 for these paired citations and reflective journal entries on regulation and attachment and reflective functioning, respectively. This approach was adopted from Carter’s (2002) first-person account in which facts and research are presented alongside journal entries. I adapted this approach to help illustrate how IPMH research intersects with my meaning-making, experiences, and applications as a coach, which are embedded in my journal entries.

Table 1. Regulation.

Table 2. Attachment and Reflective Functioning.

Experiences and Stories at the Heart of the Parallel Process (Part 2)

The existing literature suggests that HVs should be coached in a way that considers how HVs coach families (Pawl & St. John, 1998; Roggman et al., 2008; Walsh et al., 2023). As a coach, I regularly attend individual and group RS. I also have ongoing sessions with a former PAT National Center director. She describes our work together as mentoring, consulting, and coaching; please refer to Table 3 for definitions provided by Child Care Aware of America (CCAoA) and the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC; 2023), as these three terms are not interchangeable. Table 3 includes conceptual definitions of the supports I engage in as a coach of HVs.

Table 3. Support for the Coach.

I reflected on and analyzed my narratives based on my PD notes, which include my thoughts and journals about receiving RS (individual and group) and mentoring, consultation, and coaching. I have included a summary of these stories. Like Zibricky (2014), these stories use active voice to keep thick descriptions and my experience at the center of this inquiry.

Normalize the Phrase: “I don’t know, and we can look together.”

My prior experiences with coaching HVs encouraged me to treat coaching as an individualized space. I set the tone that coaches and coachees are equal through an in-take packet and during our first session by briefly underscoring the importance of our collaborative work. In my experience receiving coaching, my coach empowered me to appreciate that coaching HVs can include moments I do not know, and we can look together. Char, an experienced HV, was talking about doing home visits with pregnant women at the jail and how a newer HV sought support from her experiences with home visits with pregnant incarcerated women. Because of Char’s expectations of herself, she felt pressured to know and wanted to know. First, I assured her that regarding home visits with an incarcerated parent at the national level, experts are starting to build a repository of existing resources and explore what experience, training, and support HVs receive from working with criminal legal system-involved families. Char suggested having monthly meetings for HVs to conduct home visits at the jail to discuss their experiences and share strategies. We discussed how brainstorming together could be a strategy at the meetings. Char said she would say, ” I do not know, and we can look together in these future situations.” I shared Char’s suggestion with the Director, and Char’s idea about having an ongoing focus group with HVs conducting visits in jail was implemented.

HVs as Collectors and Sources of Data

In my first RS group experience, I shared a case about an HV and one family. To start, I provided context about the family the HV serves and information about the HV. The HV spoke about one particular family in most coaching sessions. The parent experienced six adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) in his life and had limited relational health to buffer those experiences. His child has four ACEs. The HV conveyed how tirelessly she worked to help the parent progress towards keeping his child and how she experiences secondary stress and trauma in this case. During group RS, a psychologist asked me if I knew if the parent wanted the child. This question stopped me in my tracks. I asked myself what behavior the HV saw that conveyed the parent wanted the child. I tried to come up with something and was taken aback when nothing came to mind. In my next coaching session with Ashvsita, I asked her what behaviors the parent demonstrated to keep his child. Ashvsita started to cry. She said that I gave her a perspective that she does not typically entertain, that not all parents desire to keep their children, and a reality that she has to get better at accepting. I validated her thoughts. Then, we did a breathing activity to ground us. She set the goal of mentally collecting data about which behaviors the parent demonstrates that indicate he wants to keep his child and be an effective parent. She said when she sees the parent, or he tells her about anything positive related to parenting, she would point it out as a strength because she feels the parent does not hear about strengths from the other professionals working with this family.

As a coach, my mentor taught me to encourage coaching conversations about HVs collecting their data per se and to think about what indicators they should look for that indicate movement or progress. Simultaneously, what happens if the worst happens on a visit or if the worst outcomes occur for the family? This thinking exercise can be important for anticipating success and managing challenges. HVs can engage in story-telling during coaching, as telling one’s story is a way to gain control and may promote resilience (Rhythmic Mind, 2018). Another HV, Elly, resembles a qualitative researcher who is consistently engaged in storytelling during our sessions. I processed this with my mentor, who encouraged me to explore Elly’s beliefs about storytelling. My mentor stated, “that stories are how Elly learns about families and creates meaning.” This helped me realize that it was Elly’s way for me to get to know who she is and that it ultimately led to Elly creating meaningful goals.

Metaphors

Ashvsita once shared that she feels like “a mad scientist” trying to determine what one particular family needs more or less of and how to get results. In processing this metaphor with my mentor, I realized that being “a mad scientist” sounds exhausting; it was my job as a coach to be a sounding board for Ashvsita to determine if she needed a new flask or if there were holes in the flask that made being a “scientist” more challenging. There was one hole in her flask—she often arrived 20 minutes before a visit with a parent to give the parent time to vent before the visit. The parent was in jeopardy of losing her parental rights. Albeit this demonstrated Ashvsita’s commitment to her family, it seemed tiring for both the HV and the parent. We explored replacing the vent session with rhythmic and regulation activities. Ashvsita has used other metaphors to describe her work, such as being “an esthetician,” these metaphors created a grounding space and gave a starting point for complex cases. When my mentor asked me for a metaphor to describe my work as a coach, I stated, “I need to be an agile and protective empowerer” to provide HVs with the nourishing and competent support that they provide to families they serve.

Defining Feature

My mentor coach asked me for a defining feature of my coaching sessions, which is a strengths-based approach. My coaching caseload has taken a strengths assessment as a reflective assessment that generates a person’s top strengths. In the early sessions, we explore the meaning of their strengths through the assessment alongside strengths that the HVs know they have but that were not captured in the assessment. In each coaching session, I explicitly refer to one of their strengths and reframe negative statements into strengths when applicable. I also honor the HVs as experts in their work to help us form a collaborative partnership and identify how they observe or note the families’ strengths and apply them to the families.

Simplify Complexity to Maintain Dignity as a Professional

During coaching sessions, HVs inevitably bring up complex topics like substance abuse and families with parental rights uncertainty. Coaching HVs around sensitive topics presents challenges. Herein, there are examples where HVs had questions about the parent experiencing withdrawal symptoms during visits or possibly being high. In the PAT model training, one facilitator shared that being there for families during vulnerable moments was essential. My mentor’s perspective differed, and she conveyed that situations including substance abuse warrant more attention. She matter-of-factly explained that if a HV was completing a home visit with a parent who is a cancer patient, and they felt weak and shaky during the visit and maybe had to throw up, many professionals would terminate the session. This example made things crystal clear; HVs must stay authentic in complex situations and have dignity in their vital work. Situations in which HVs believe or observe that a parent is experiencing withdrawal or under the influence and necessitates care beyond the HV.

I heard about burnout at the start of a coaching session with Ashvsita concerning a parent struggling with withdrawal symptoms and sometimes being engaged in visits and other times working with engagement. She referred to it as a “heavy case.” Our joint reaction was to make a plan to accommodate the various ways the parent may show up to the visit. I felt like we were doing something, solving a problem, but immediately, I felt exhausted by that prospect. This was a contagious situation—the HV’s weight, in this case, was slowly shifting to my weight. I called it out by stating, “Whoa, this feels like a lot; we can choose to carry it or to further look at it. Let’s look at it together.” She quickly agreed.

I took a few moments to pause during our session and started to consolidate what my mentor taught me. I let the HV know there is no magic approach and that her current preparation is more than enough. I asked her what the approach to the visit would have been if it had been simplified. Ashvsita said, “I am listening.” I recalled a visit of hers that I observed. During this visit, she noticed where the parent and child were seated and where everyone in the triad was. This intentional placement allowed the parent to drive the visit and frequently interact with the child, a strategy she could use with her “heavy case.” My mentor suggested using watch, wait, and wonder (see Cohen et al., 1999) to simplify the interaction further. When I shared this technique with Ashvsita, she said the parent tends to watch his child with interest. She said she would help him follow the child’s needs, which we both agreed eases the pressure of setting the stage for an activity during the visit. Finally, the HV was intrigued by assisting the parent in wondering what the child’s perspective is.

Beginner’s Mind Gone: Balance of Providing Strategies with Support for HVs’ Finding Own Answers

After one of my first coaching sessions with a HV, she thanked me for all the strategies shared during the visit, which I had mixed feelings about. I understand the value of sharing or gaining strategies, but I want coaching to be a learning exchange. In this exchange, methods can be explored, and care needs to be taken to understand the context and how a strategy may be applied or individualized to a family. Coaching is not always comfortable; the discomfort is often where the learning is. As I coach, my mentor taught me to pause and summarize the themes I hear if an HV has a lot to say on a topic and to apply the themes to the coaching agenda to create a collaborative summary of the session. One question that continuously arises is, “Have I lost my beginner’s mind that put HVs in the expert position?” In 2017, it was easy for me to always put HVs in the expert position. My knowledge base has vastly expanded since then, but I always try to keep this question in mind as it helps me have a nimble mind and aim for collaborator and facilitator approaches.

One of my primary tasks as a coach is to promote HVs’ goal-setting. Goals represent a framework to achieve desired outcomes (Bailey, 2019; Maes & Karoly, 2005). The coachee can be encouraged to consider where they can be outstanding (Crotaz, 2022) and set goals in several domains, such as professional practice and well-being (Collison & Wolf, 2022). It is essential to consider strengths and think about what individuals have the best chance of reaching (Collison & Wolf, 2022). Operationalizing these concepts, coaches should include goal setting related to the HVs’ PD, strengthening specific HV practices or skills, the client’s regulation, and those important to the HV. My mentor emphasizes that goal-setting does not have to include a large and complex goal; it can consist of mini-goals, which can be things the HV already does well.

New Knowledge about Coaching HVs from HVs (Part 3)

I identified three revised themes using coding and personal reflection from the HV coaching interviews: (1) understanding the coaching climate to bring regulation, relation, and coaching together, (2) coaching as a resource for decision-making, and (3) balancing strengths and sensitivity to challenges in coaching.

Understanding the Coaching Climate to Bring Regulation, Relation, and Coaching Together

In my interviews with HVs, they described a coaching climate that values “authenticity,” “a nonjudgmental approach,” “HVs feeling whole,” “a grounding place,” and “includes empathy and mutual respect.” One HV said coaching provides “time to regulate and exhale:”

In coaching, it’s just me and the coach. We’re bringing things to the forefront and working through how to tackle what needs to be tackled in my work with families, taking time to breathe, and celebrating the things that need to be celebrated.

Another HV noted that she thinks “coaching is therapeutic,” and she feels “connected during coaching,” and relation is the second sequence in the neurosequential engagement model. HVs expressed that regulation and relation, both critical components of the NMT and NMRS, occur during coaching. HVs also expressed that coaching is a place for “reflection,” and how HVs operate in higher parts of their brains is addressed in the next theme.

I reflected on a HV stating that she feels “connected during coaching” and the ways that I coach HVs and how they may make the families they serve feel. I feel connected to my mentor when she says something and asks if there are things I could relate to from her experiences. In the IPMH literature, these questions create reveries or connections (Brandt & Perry, 2024) and help me understand my experience of staying present and attuned and ready for reflection. As a coach and researcher, I realized that both coaching and interviewing are processes that can change the thinking and connection of both participants in the dyad (home visitor-as-coachee and coach).

Coaching as a Resource for Decision Making

This theme captured HVs’ expressions that coaching is “a resource” and “part of a bigger PD system” that helps HVs “make decisions about their practice and well-being.” HVs underscored to me the necessity of a coaching resource that helps with decision-making. All HVs described coaching as a space to “consider a different perspective,” “gain a broader perspective,” or “appreciate perspectives.” All HVs described coaching as a space to plan and reflect on what’s working and what is not and viewed coaching as a place to review their practice and playback practice via video and/or discussions about an observation of a home visit. HVs expressed satisfaction with coaching, and one expressed that “having it once a week rather than every other week or monthly” would improve it. Another HV explained, “I feel like you [coach] have been helpful to me a lot,” and she has learned “what is included in coaching and when she needs to talk about something with her supervisor.”

Balancing Strengths and Sensitivity to Challenges in Coaching

This theme addressed that coaching is a strengths-based process, and it is balanced with a coach’s sensitivity to HV challenges. All HVs expressed to me that coaching is strengths-based work, which reflects how I coach them and potentially how they work with their families. One HV said it is a reminder “to use skills that I already possess” to “evaluate strengths and growing points.” HVs also alluded to the parallel process. One HV said, “Sometimes we’re the only professionals trying to point out their [families] strengths.” The coaching narrative of what is going well and encouraging what strengths the HVs noticed is balanced with coaching as a space “to be honest about challenges.” Coaching is a place to celebrate successes with families, reflect on what the HV did to support their success, and be honest about the challenges and issues with the families served, HV practices, and HV regulations.

Conclusion

By interweaving and reflecting upon autoethnography, infant mental health concepts, and interviews with HVs, this article advances adult regulation and educational transformation by addressing the critical need for effective reflective coaching among EC HVs. HVs are pivotal in supporting parents, thereby influencing children’s development. However, translating coaching strategies into HVs’ work with at-risk families presents challenges, highlighting the necessity for support to enhance transferability. I think ways to enhance transferability include mindfulness and connection. Mindfulness includes regulation and nonjudgmental awareness of one’s experience (Bishop et al., 2004; Kabat-Zinn, 20023), and greater levels of mindfulness in home visitors are associated with a strong working alliance (Becker et al., 2016) and thus a more empathetic response to families and a better understanding of families’ goals (Becker et al., 2016; Snyder et al., 2012). Emphasizing HVs’ vulnerabilities, including secondary stress and burnout, underscores the importance of addressing educators’ emotional well-being in educational settings. This article addresses strengthening coaching processes to promote HVs’ dual regulation and, potentially, practice.

My autoethnographic approaches also highlight that HV coaching involves making connections between theory and practice, coaches and home visitors-as-coachees, and the families HVs coach. Realizing these connections requires deeply reflective and self-regulating work, including the type of self-reflection that is commonly employed in autoethnography. Providing personal insights through autoethnography such as mine can enhance practitioners’ understanding of the human element and the connections promoted in coaching. The practice insights may offer actionable strategies to support HVs in educational settings, fostering a focus on HVs’ well-being alongside PD and facilitating educational transformation for coaching.

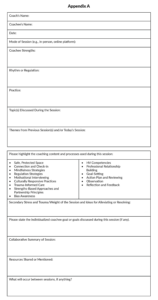

Throughout this reflective process, I intently thought about coaching processes and created the documentation form in Appendix A. In addition to this form, I journaled about most sessions (some of my entries were captured earlier in this article). I refined my coaching voice and philosophy throughout this process. My reflection leads me to suggest the next steps for the field to continue to consider: My coaching work in 2017 was in person, and currently, it is via an online platform. I think the mode or modes of coaching warrant further investigation.

Reflecting on my coaching experiences helped me realize the importance of both coaching and RS for home visitors and coaches. I receive support as a coach through CoPs, RS, and coaching/mentoring/consultation. Are other home visitor coaches receiving support? What is the recommended dosage for professional efforts to support the coach? Are home-visiting programs able to hire coaches in addition to reflective supervisors? What should the sharing process, if any, look like between reflective supervisors and coaches if they are different people?

Coaching and autoethnography make multi-layered connections that demand reflective and self-regulating work. More narrative work is needed from the home visiting field. Other descriptive work, such as audio or video transcripts analysis, is needed (Walsh et al., 2021; West et al., 2024) to advance coaching training and implementation practices and fidelity. Many HVs also consider themselves coaches (Walsh et al., 2023), meaning that HVs often listen and watch during coaching and think of ways to try the strategies they received in coaching with the families they serve. Perry’s (2009) “regulate, relate, and reason” approach may be a natural fit for coaching home visitors and potentially for home visitors to work with at-risk families.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Melissa Burnham and the Department of Human Development, Family Science, and Counseling for sponsoring the first author’s 2023-2024 Infant-Parent Mental Health Fellowship (IPMHF) through UC Davis Continuing and Professional Education, the Parent-Infant & Child Institute in Napa, and the Neurosequential Model Network. Thank you to the Department for changing my role statement to allow me to work as a coach at the University of Nevada Reno’s home visiting program.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose. The University of Nevada, Reno IRB approved this research with human participants.

References

Adams, T. E., Jones, S. H., & Ellis, C. (2022). Making sense and taking action: Creating a caring community of autoethnographers. In T. E. Adams, S. H. Jones, & C. Ellis (Eds.), Handbook of autoethnography (2nd ed., pp. 1–19). Routledge.

Adams, T. E., Jones, S. H., & Ellis, C. (2015). Autoethnography. Oxford University Press.

Alitz, P. J., Geary, S., Birriel, P. C., Sayi, T., Ramakrishnan, R., Balogun, O., Salloum, A., & Marshall, J. T. (2018). Work-related stressors among Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting (MIECHV) home visitors: A qualitative study. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 22(Suppl 1), S62–S69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-018-2536-8

Allen, J. G. (2006). Mentalizing in practice. In J. G. Allen and P. Fonagy (Eds.), Handbook of Mentalization-Based Treatment (pp. 1–30). Wiley.

Allen K. (2016). Theory, research, and practical guidelines for family life coaching. Springer.

Artman-Meeker, K., Fettig, A., Barton, E. E., Penney, A., & Zeng, S. (2015). Applying an evidence-based framework to the early childhood coaching literature. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 35, 183–196. https://doi.org/10.1177/0271121415595550

Bailey, R. R. (2019). Goal setting and action planning for health behavior changes. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 13, 615–618. https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827617729634

Barron, C. C., Dayton, C. J., & Goletz, J. L. (2022). From the voices of supervisees: A theoretical model of reflective supervision (Part II). Infant Mental Health Journal, 43, 226–241. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21975

Becker, B. D., Patterson, F., Fagan, J. S., & Whitaker, R. C. (2016). Mindfulness among home visitors in Head Start and the quality of their working alliance with parents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25, 1969-1979. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0352-y

Begic, S., Weaver, J. M., & McDonald, T. W. (2019). Risk and protective factors for secondary traumatic stresses and burnout among home visitors. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 29, 137–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2018.1496051

Bishop, S. R., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N. D., Carmody, J., Segal, Z. V., Abbey, S., Speca, M., Velting, D., & Devins, G. (2004). Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11, 230-240. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bph077

Bochner, A. P. (2012). On first-person narrative scholarship: Autoethnography as acts of meaning. Narrative Inquiry, 22, 155–164. https://doi.org/10.1075/ni.22.1.10boc

Brandt, K. (2024, March 3). Mentalization-based strategies [Presentation]. Neurosequential Model in Reflection and Supervision. The Napa Parent-Infant Child Institute.

Brandt, K. (2023, April 14). Neurosequential Model of Reflection and Supervision: Relax, reflect, and refuel. University of California, Davis, Infant-Parent Mental Health Fellowship Program.

Brandt, K., & Perry, B. (2024, March 25-26). Reflection and supervision Neurosequential Model of Reflective Supervision. Parent-Infant Child Institute.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. Sage.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32, 513-531. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513

Carter, S. (2002). How much subjectivity is needed to understand our lives objectively? Qualitative Health Research, 12, 1184–1201. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732302238244

Chang, H. (2016). Autoethnography as method. Routledge.

Child Care Aware of America & National Association for the Education of Young Children [CCAoA]. (2023). Early care and education professional development: Training and technical assistance glossary. https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/our-work/public-policy-advocacy/new_glossary.pdf

Circle of Security International. (2018). COSP facilitator manual. https://www.circleofsecurityinternational.com/cosp-facilitator-training/

Cohen, N. J., Muir, E., Lojkasek, M., Muir, R., Parker, C. J., Barwick, M., & Brown, M. (1999). Watch, wait, and wonder: Testing the effectiveness of a new approach to mother-infant psychotherapy. Infant Mental Health Journal, 20, 429-451. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0355(199924)20:4<429::AID-IMHJ5>3.0.CO;2-Q

Collison, J., & Wolf, R. (2022). How to set strengths-based goals [Webinar]. Gallup CliftonStrengths. https://www.gallup.com/cliftonstrengths/en/389366/how-to-set-strengths-based-goals.aspx

Cosgrove, K., Gilkerson, L., Leviton, A., Mueller, M., Norris-Shortle, C., & Gouvêa, M. (2019). Building professional capacity to strength parent/professional relationships in early intervention: The FAN approach. Infants and Young Children, 32, 245–254. https://doi.org/10.1097/IYC.0000000000000148

Crotaz, G. (Host). (2022, October). 132 Maika Leibbrandt: Feature-Length Sequel to Ep 42 – From Scarcity To Abundance, The True Power Of An Unlock Moment [Audio podcast]. Apple Podcasts. https://podcasts.apple.com/gb/podcast/132-maika-leibbrandt-feature-length-sequel-to-ep-42/id1613086637?i=1000648264403

Dana, D. (2023, August 12). Porges’ Polyvagal Theory. University of California, Davis, Infant-Parent Mental Health Fellowship Program.

Denmark, N., Adelstein, S., West, A., & Sparr, M. (2024, April 2). How can you contribute to testing a measure of reflective supervision for home visiting? Supporting and strengthening the home visiting workforce (SAS-HV) [Webinar]. James Bell Associates.

Dexter, C. A., & Wong, K. (2024). Circle of Security-Parenting randomized waitlist control study: Change in reflective functioning explains positive caregiver behavior. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 33, 504–514. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-023-02710-0

Elek, C., & Page, J. (2018). Critical features of effective coaching for early childhood educators: A review of empirical research literature. Professional Development in Education, 45, 567–585. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2018.1452781

Fonagy, P., Steele, M., & Steele, H. (1991). Maternal representations of attachment during pregnancy predict the organization of infant-mother attachment at one year of age. Child Development, 62, 891–905. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01578.x

Fonagy, P., & Target, M. (2005). Bridging the transmission gap: An end to an important mystery of attachment research? Attachment and Human Development, 7, 333–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730500269278

Gilkerson, L., & Gray, L. (2023, March 18). Fussy babies: Assessment and intervention. University of California, Davis, Infant-Parent Mental Health Fellowship Program.

Gilkerson, L., & Imberger, J. (2016). Strengthening reflective capacity in skilled home visitors. Zero to Three. https://eitp.education.illinois.edu/Files/Series/FAN/ZTTarticle1.pdf

Graner, L. (n.d.). Everyone can BeRhythmic. https://www.berhythmic.com/

Graner, L. (2023, October 5). Breath, body & the beeat 1: Breathe [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/50KdxxD9Yno?si=3PYXK_KrZC8bzoiC

Grimes, H. R. (2023, June 10). Racial, gender, and ethnic justice issues in pregnancy, childbearing, and parenting. University of California, Davis, Infant-Parent Mental Health Fellowship Program.

Haring, C., & Rau, A. (2024). Coaching in home visiting: Supporting better outcomes for professionals and families. Brookes.

Head Start, ECLKC. (2022, June 13). Practice-based coaching. https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/desarrollo-profesional/articulo/practice-based-coaching-pbc

Hoffman, K. T., Marvin, R. S., Cooper, G., & Powell, B. (2006). Changing toddlers’ and preschoolers’ attachment classifications: The Circle of Security intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74, 1017–1026. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.74.6.1017

Isner, T., Tout, K., Zaslow, M., Soli, M., Quinn, K., Rothenberg, L., & Burkhauser, M. (2011). Coaching in Early Care and Education Programs and Quality Rating and Improvement Systems (QRIS): Identifying Promising Features. Child Trends. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED579791

James, J. (2015). Autoethnography: A methodology to elucidate our own coaching practice. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring, 9, 102–111. http://ijebcm.brookes.ac.uk

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10, 144-156. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bpg016

Kempster, S., & Iszatt-White, M. (2013). Towards co-constructed coaching: Exploring the integration of coaching and co-constructed autoethnography in leadership development. Management Learning, 44, 319–336. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507612449959

Lewis, J. J. (2023). The process of one-to-one coaching supervision from the perspectives of the coach and coaching supervisor: What do coaching supervisors actually do? International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring, 21, 268–284. https://doi.org/10.24384/j7e3-y574

Lillas, C., & Turnbull, J. (2009). Infant/child mental health, early intervention, and relationship-b ased therapies: A neurorelational framework for interdisciplinary practice. Norton.

Maes, S., & Karoly, P. (2005). Self-regulation assessment and intervention in physical health and illness: A review. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 54, 267–299. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2005.00210.x

Marvasti, A. (2006). Being Middle Eastern American: Identity negotiation in the context of the war on terror. Symbolic Interaction, 28, 525–547. https://doi.org/10.1525/si.2005.28.4.525

Mavridis, C., Harkness, S., Super, C. M., & Liu, J. L. (2019). Family workers, stress, and the limits of self-care. Children and Youth Services Review, 103, 236–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.06.011

McLeod, R. H., Akemoglu, Y., & Tomeny, K. R. (2021). Is coaching home visitors an evidence based professional development approach? A review of the literature. Infants & Young Children, 34, 95–108. https://doi.org/10.1097/IYC.0000000000000186

Meuwissen, A. S., & Watson, C. (2022). Measuring the depth of reflection in reflective supervision/consultation sessions: Initial validation of the reflective interaction observation scale (RIOS). Infant Mental Health Journal, 43, 256-265. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21939

Neurosequential Network. (n.d.). Neuroseqeuntial model. https://www.neurosequential.com/nmt

Patten, M. L., & Newhart, M. (2018). Understanding research methods: An overview of the essentials (10th ed.). Routledge.

Pawl, J. H., & St. John, M. (1998). How you are is important as what you do . . . in making a positive difference for infants, toddlers, and their families. Washington, DC: Zero to Three: National Center for Infants, Toddlers and Their Families.

Perry, B. D. (2009). Examining child maltreatment through a neurodevelopmental lens: Clinical applications of the Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 14, 240-255. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325020903004350

Perry, B. D. (2023, May 19). Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics (NMT). University of California, Davis, Infant-Parent Mental Health Fellowship Program.

Perry, B. D., & Winfrey, O. (2021). What happened to you? Conversations on trauma, resilience, and healing. Flatiron Books.

Poulos, C. N. (2021). Essentials of autoethnography. American Psychological Association.

Poulos, C. N. (2013). Autoethnography. In A. A. Trainor & E. Grace (Eds.), Reviewing qualitative research in the social sciences (pp. 38–53). Routledge.

Roggman, L. A., Boyce, L. K., & Innocenti, M. S. (2008). Developmental parenting: A guide for early childhood practitioners. Brookes.

Rush, D. D., & Shelden, M. L. L. (2020). The Early Childhood Coaching Handbook. Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

Rhythmic Mind. (2018, June 7). Dr. Bruce Perry interview [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/a9NtmRj0tm8?si=WDqZ8UCz5Cfj7EkA

Slade, A. (2007). Reflective parentingparenting programs: Theory and development. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 26, 640–657. https://doi.org/10.1080/07351690701310698

Slade, A. (2005). Parental reflective functioning: An introduction. Attachment & Human Development, 7, 269–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730500245906

Snyder, R., Shapiro, S., & Treleaven, D. (2012). Attachment theory and mindfulness. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 21, 709-717. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-011-9522-8

Stacks, A. M., Jester, J. M., Wong, K., Huth-Bocks, A., Brophy-Herb, H., Lawler, J., Riggs, J., Ribaudo, J., Muzik, M., Rosenblum, K. L., & the Michigan Collaborative for Infant Mental Health Research. (2022). Attachment & Human Development, 24, 53–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2020.1865606

The Regents of the University of California, Davis. (n.d.). Continuing and professional Education, Napa Infant-Parent Mental Health Fellowship. https://cpe.ucdavis.edu/child-development/napa-infant-parent-mental-health-fellowship

Tobin, M., Carney, S., & Rogers, E. (2024). Reflective supervision and reflective practice in infant mental health: A scoping review of a diverse body of literature. Infant Mental Health Journal: Infancy and Early Childhood, 45, 79-117. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.22091

Tomlin, A. M., & Viehweg, S. A. (2024). Tackling the tough stuff: A home visitor’s guide to supporting families at risk (2nd ed.). Brookes.

Walsh, B. A., & Blewitt, P. (2006). The effect of questioning style during storybook reading on novel vocabulary acquisition of preschoolers. Early Childhood Education Journal, 33, 273-278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-005-0052-0

Walsh, B. A., & Chapdelaine, A. (2004). Toddlers’ ability to distinguish between grammatical and ungrammatical sentences as a function of prosody and imagery. Psi Chi Journal of Undergraduate Research, 9, 8-13. https://doi.org/10.24839/1089-4136.JN9.1.8

Walsh, B. A., Innocenti, M. S., Manz, P. H., Start Early, Cook, G. A., & Jeon, H. J. (2023). Conceptualizing coaching within the home visiting field. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 44, 642–659. https://doi.org/10.1080/10901027.2022.2125464

Walsh, B. A., Innocenti, M. S., Start Early, & Hughes-Belding, K. (2022). Coaching home visitors: A thematic review with an emphasis on research and practice needs. Infant Mental Health Journal, 43, 959–974. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.22016

Walsh, B. A., Manz, P. H., Mogbojuri, O., Jeon, H. J., Johnson-Shelton, D., & Lee, M. (in review). Supporting the well-being of Early Head Start home visitors: A mixed-methods study.

Walsh, B. A., Steffen, R., Manz, P. H., & Innocenti, M. S. (2021). An exploratory study of the process of coaching Early Head Start home visitors. Early Childhood Education Journal, 49, 1177–1188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-020-01119-4

Weisner, T. S. (1977). The ecocultural project of human development: Why ethnography and its findings matter. Ethos, 25, 177-190.

Wenger, E., McDermott, R., & Snyder, W. M. (2002). Cultivating communities of practice. Harvard Business School.

West, A. L., Berlin, J. J., & Jones Harden, B. (2018). Occupational stress and well-being among Early Head Start home visitors: A mixed method approach. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 44, 288–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2017.11.003

West, A., Madariaga, P., & Sparr, M. (2022). Reflective supervision: What we know and what we need to know to support and strengthen the home visiting workforce (OPRE Report No. 2022-101). Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

West, A., Spinosa, C. Z., DeVoe, M., Madariaga, P., & Barnet, B. (2024). Implementation of training and coaching to improve goal planning and family engagement in early childhood home visiting. Children and Youth Services Review, 163, 107733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2024.107733

Willig, C. (2014). Interpretation and analysis. In U. Flick (Ed.), The SAGE Handbook of qualitative data analysis. Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446282243

Zibricky, C. D. (2014). New knowledge about motherhood: An autoethnography on raising a disabled child. Journal of Family Studies, 20, 39–47. https://doi.org/10.5172/jfs.2014.20.1.39

Appendix A

Authors

Bridget A. Walsh and Child and Family Research Center Home Visitors¹

University of Nevada, Reno

United States

¹Avis Moore, Chantell Whaley, and Milagro Guardado