Dear colleagues and friends,

We have launched the Call for Papers for our 2016 WAIMH Congress in Prague, Infant Mental Health in a Rapidly Changing World: Conflict, Adversity, and Resilience, hosted by Israeli and Palestinian Infant Mental Health Associations. I wish to share with you, in these few paragraphs, an unexpected experience related to these themes when I was in Tokyo attending the 6th World Congress on Women’s Mental Health, together with Palvi Kaukonen and our host and dear colleague, Hisako Watanabe. In the congress we had a WAIMH Symposium: Trauma, depression and resilience from the lens of Infant Mental Health.

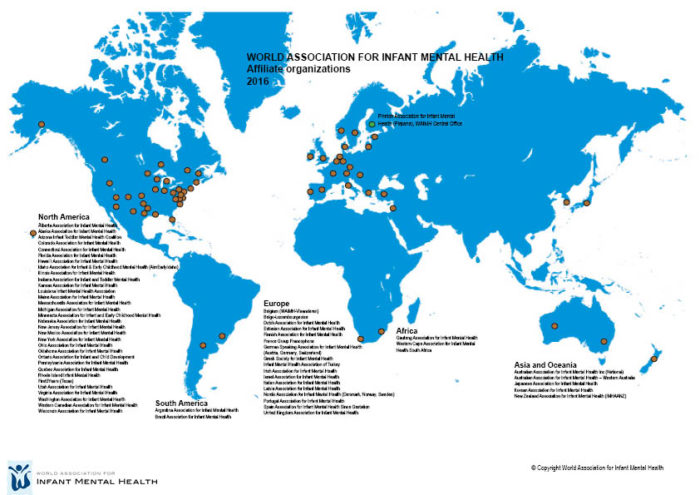

We were in Tokyo also for a Pre-conference WAIMH training day arranged by theJapanese Association for Infant Mental Health. It was a very successful event with participants from all over Japan. We also met the Board of the Japanese affiliate and were able to get involved in issues of infant mental health development on cultural as well as organizational level (see photo on page 18).

Play car Morimori

On the only free day we had we went for a walk in the Yanaka neighborhood, a quiet, traditional and less touristy part of Tokyo. We enjoyed a leisurely stroll, looking at the tiny, neat and flower-filled houses, entering small shops (women on a vacation day…!), far from thoughts about adversities and resilience. As we turned the corner of one of these small streets, our eyes caught a gathering of young kids with their parents. Curious, as infant mental health people often are, we got closer and saw a young man standing in the middle of toddlers and parents, explaining something (in Japanese, of course!). Around him were all kinds of wooden toys and musical toys spread on plain mattresses. At first, we thought it was a kind of Sunday outdoor playground for young parents and kids. At some point, we observed all the parents and toddlers suddenly laying down on the ground, hands covering their heads. The kids were playful; the grown-ups were somewhat sober. A young woman approached us – the typical foreigners observing what was happening – and explained, “This is an Earthquake Simulation Teaching Play, so kids and parents learn what to do.” She smiled gently at our puzzled looks and told us that she and her husband had been doing this all around the country since 2011, after the Great East Japan Earthquake and radiation accident. She went on to explain, “You see, it becomes part of the playtime and is much less frightening than a formal training …even the younger ones understand. They will remember what they need to do in the case of a new earthquake.”

After a while we saw the young man grabbing a teddy bear and showing different ways of quickly wrapping it with the help of only a belt and a plain T-shirt and carrying it like in a kangaroo pouch. It taught to parents how to carry their infants if they have to run for cover.

“Desensitization, mastery and control through being well-informed” would be our professional words. This young couple intuitively understood the power of play in supporting resilience at the community level and have made it their own personal mission.

Trauma and Play

Returning to the World Congress on Women’s Mental Health and to our symposium on trauma, depression and resilience, one of the participants commented and asked, “We have so many mass traumas nowadays that individual psychotherapies for all are totally irrelevant. What would you suggest as a way to intervene?” We told them about the couple teaching about an earthquake and what to do as a wonderful way to create resilience in response to trauma.

Two days later, Hisako took us to Kooriyama, the capital of the Fukushima region. We visited the PepKids Koriyama center that Kaija Puura described in the winter 2015 issue of Perspectives. Again, playfulness and the use of play to acquire trauma-related coping skills seemed to be a core component of the Japanese resilience kit for mass trauma.

When there are no children around, the adult’s internal playfulness is not triggered and coping is more difficult. This is what we saw on our way to Idate, the village most severely hit by radiation. It is still closed to its inhabitants who were all farmers with wide houses and fields. The houses looked intact, as if nothing had happened. They were not destroyed by the earthquake, but the soil is filled with radiation. Only a few elderly people can be seen in the streets, very few cars are on the road, and there are no kids. Our driver, Mr. NIshida, who once lived in this village, made a sharp turn up a hill to show us the deserted elementary school of the village. Only the statue of a child and a radiation counter that showed that the radiation level was above the norm told us the story.

We had left a sunny Tokyo at 10 a.m. When we arrived at 5 p.m. at the Date Evacue Center, a strong cold wind hit our faces, as if resonating with what we were about to see and hear. We went along the “streets” of the camp, looking for “our man”, Mr. Kenichi Hasegawa. Rows of tiny, identical, anonymous-looking houses where people had been living for an undetermined time conveyed a heavy feeling of sadness. Mr. Hasegawa, a sober looking farmer in his late fifties, led us to the gathering room of the camp and started telling us about his public fight for letting the truth come out. He is the leader of the evacuated village and in that role demands that the Japanese Government recognize their unforgivable fault of having postponed the children’s evacuation 4 months after the earthquake, as well as not letting the people know that the level of radiation was extremely high. Radiation particles have since then been traced in the children’s urine. Elderly people were convinced by the Mayor to stay in their homes, but young family members have been mandated by the Mayor to provide their needs, thus also exposing them to radiation. To the question, “Do you have any idea how long it will take until you return home?” Mr. Hasegawa’s face became even more somber and his answer made us realize how catastrophic the aftermath of the Tsunami is:

“Children will never come home – back to Idate. It is too dangerous as the radiation only gets deeper into the soil because it was not well decontaminated from the beginning. Today, the ground is covered by leaves. My sons, who were supposed to continue to farm our land, have been forced to go and look for other farms in another region. Idate will in fact disappear; its land is worthless, even though its Photos from Fukushima. Temporary housing (on top) and Pep Kids Koriyama, Fukushima. Fom left to right: Jyrki and Palvi Kaukonen, Hisako Watanabe, Shintaro Kikuchi, Miri Keren, Keeko Omori and Yoko Hayashi. houses have not been hit by the Tsunami. Families have been torn apart, many men have become alcoholic, and some have committed suicide. We have lost everything, besides our very lives, but we refuse to give up. We want to let the world know what is going on here. This is why I agreed to come and talk to you, even though you are foreigners.”

We all remained wordless, speechless. Hisako will present all the statistics and figures that this gentleman has collected at our Congress in Prague.

We went back to our minivan; it was after 8 p.m. Some of the camp houses were lighted, while others remained in the dark. A cold wind was blowing furiously. Palvi, Hisako and I looked at one another, with a shared feeling of humbleness towards those people who had lost so much, yet refused to be passive victims in response to devastating loss.

Reflecting

This one single day felt like a week; it was so full. We ended it with a traditional Japanese dinner at the hotel. Only then could we begin to reflect on what we saw, felt, and heard:

About the multi-faceted and vast disaster

“Japanese people usually do not reveal their negative feelings, I am surprised at how willing they were to share with us the truth of this multi-faceted disaster, to speak out their anger and frustration at the government, to disclose the rising tensions and loss of cohesiveness among the evacuees, and to even tell us about how their own family has been inflicted,” reflected Hisako. They really wanted us to know and to spread the word. This fight for the truth has become their mission and they have chosen to cope by remaining active rather than falling into passive despair.

About the use of playfulness as a facilitator of recovery after a mass trauma

Nobody but local professionals such as Dr Shintaroh Kikuchi (the pediatrician and leader of the PepKIds Koriyama), and Mrs. Oomori , Psychologist, could have thought of the PEP Kids amazing project. Indeed, they were among those who saw their children become pale and sad…they were among those who needed to cope with their own existential fears of radiation and uncertainty. Being parents themselves, they let “the child inside them” emerge in the form of this huge indoor playful space, where motor activity and pretend play are the main forms of expression. Play for children is like work for adults. Play conveys energy, as well as a wish to thrive and achieve. The absence of play among normally developing children is an indicator of depression or severe physical illness. Fukushima children were indeed at risk of becoming emotionally sick, after having been confined at home for a year. Now, in turn, the revived children’s playfulness is helping their surrounding grown-ups to revive their own libido; their zest and hope in life.

Would Alicia Lieberman say that this is an example of a positive feedback loop of angels? Would Selma Fraiberg call the Truck Play “Psychotherapy in the Street?” These are things for us to wonder about as we think about trauma and its consequences for infants, young children and adults.

I invite each one of you to send abstracts and to come to Prague to continue to wonder and to reflect on ways to reduce the risk of emotional disturbance in the early years and to promote infant mental health.

Personal Reflections about Trauma and Play and an Invitation to Reflect

Authors

Keren, Miri, MD,

WAIMH President,

ofkeren@zahav.net.il,

Israel